“I spend a lot of time trying to take photographs. But I can go days and not take a single frame.”

At the recent VIEW Conference, cinematographer Sir Roger Deakins CBE (1917, Blade Runner 2049, Skyfall, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, Sicario) was a guest of the event in conversation with director Dean DeBlois. The two had collaborated on the animated How to Train Your Dragon series.

The DOP was an incredible addition to VIEW, which largely focuses on animation and VFX. Of course, with his contributions to several animated films now, and having worked on big visual effects features like 1917 and Blade Runner 2049, Deakins has a unique perspective on that side of filmmaking.

In this interview with befores & afters, done over Zoom, Deakins talks about his thoughts on the cross-over between cinematography and visual effects, including the advent of previs. And we discuss the Team Deakins podcast, in which Deakins and his wife James talk to many other filmmakers about the craft. Deakins also mentions his new book, Byways, of personal stills photography, which he refers to as his “personal scribbles”.

b&a: Roger, I am obsessed with your podcast, I have to tell you that straight away. One of the reasons is, I feel like when you and James and other hosts and your guests talk, it’s like you are learning new things yourselves, despite of course your significant filmmaking experience.

Roger Deakins: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I don’t think the conversations would really work unless we were interested in what people were saying. The first question that we often ask is, how did you start out? How did you get where you are? Very few people, I know their background previously to the podcast, even people we know fairly well. I don’t know the details of the way they got into the business, so that’s always interesting.

b&a: The John Seale one, where he talks about being a jackaroo in Australia, that really shaped his career, didn’t it?

Roger Deakins: Absolutely. I knew a little bit about it, because we’ve often met up in the past. When he started really going into the details, it was great, and he’s such a brilliant talker.

b&a: Why did you start the podcast? Was it related to the lockdown?

Roger Deakins: No, it’s my wife James’ idea. We do a little website where people can ask questions. It started off as an extension of that in a way. We thought we were going to talk to people that we knew and work with, and they would talk about different aspects of filmmaking. Then the pandemic came along and it just expanded. For us, it was a wonderful way to keep in touch with people we knew, but also to meet people we’d never met. Wonderful.

b&a: I also like that even when you interview people you’ve actually worked with on a film, you seem to learn new things from them about the actual production.

Roger Deakins: Right, exactly. When you’re on a film you’re so intensely into your own world and there’s a lot of things that are incidental that you miss. Like, obviously, other people’s challenges that you might not have fully appreciated.

b&a: I did want to ask you about your interaction with visual effects. I was going back through your filmography thinking, what for you was the first film where you really came up against a lot of visual effects challenges?

Roger Deakins: Well, most films I’ve worked on really have been as much as possible in-camera. And then you get specific challenges, like on Unbroken with Angelina Jolie, filming in the bomber on stage because obviously we couldn’t be flying. There you get the whole discussion about, ‘Okay, what’s outside?’ I mean, I’ve got a real revulsion of bluescreen, especially a situation like that. Because you put a bluescreen there, it’s like, okay, how are you going to light it? Because basically the interior plane is being lit by what’s reflecting in from the sky. So you have those conversations with the effects artists, and then you find a way to do both, to make it work for both teams really.

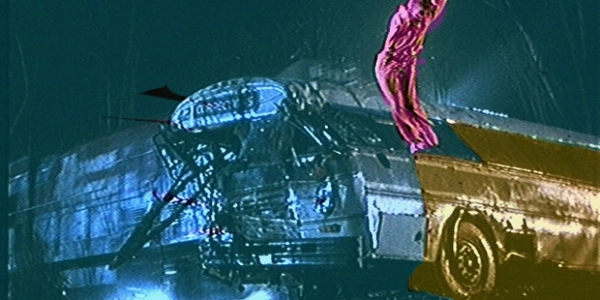

b&a: Yes. I was also thinking, going back to something like Hudsucker Proxy, which in many ways is more of the old school kind of visual effects filmmaking with miniatures and then some early digital augmentation.

Roger Deakins: Yes, there were effects extensions to buildings, and the whole opening was a built model that we shot in a very old-fashioned way. Then there’s that shot, going over the Hudson towards the cityscape at night, which I remember was intended to be an effects shot. And it was in the budget to be an effects shot. But because we had built the model for the opening, I said to Joel and Ethan, ‘Why can’t we do that in-camera? We could just basically fill the stage with an inch of water and use the of models to create the city.’ Which is what we did. So it was actually totally in-camera.

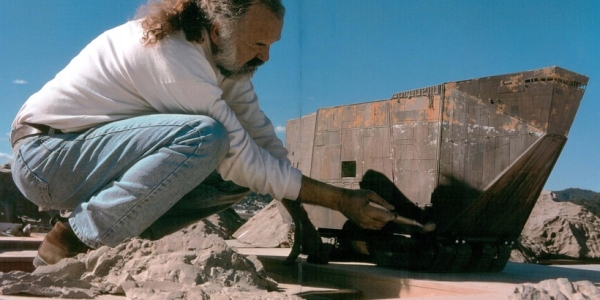

Even where you can’t do everything in-camera, you try and do as much as possible. I mean, Blade Runner 2049 is obviously one where we had the most complex visual effects work. But we did things like, we built a little model of a wide shot of the records library. It was just a basic shape model that I could light with a moving light. The VFX people then could take that as a reference and reproduce exactly the lighting and the way the light falls in the space.

A visual journey inside the miniatures of ‘The Hudsucker Proxy’

b&a: Sometimes in the history of visual effects filmmaking, it feels like VFX has always been a very separate process. But I think you would say, why shouldn’t it be an extension of the main photography or main production?

Roger Deakins: Right. Also, an effects artist working on a shot in isolation might, I mean, we had this on Blade Runner, this issue about working in isolation. Somebody came back with a wonderful wide shot of this abandoned upturned radio mast. And it was quite beautiful, but there was a sun in the sky. And there was all this reflected light. And we said, ‘But there is no sun in this world. The sun is not out, it’s completely gloomy. And we want it to look really ugly.’

You can’t blame the person for doing it and making it look really beautiful. And it did look beautiful, but it wasn’t right for the film. And that’s the danger without having, I think, the cinematographer and the director involved all the way through, so they can keep a kind of continuity to the look.

b&a: What’s your process early on a film in terms of your relationship with the VFX supe? Do you get a chance to sit down and have long conversations with them, just like you might do with other HODs?

Roger Deakins: Oh, very much so. It really starts off with just conversations with a director. And then gradually once you build the concepts, then that extends. The production designer and then a visual effects supervisor and the core group of people just expands. And the conversation just expands, so more and more ideas come in as things get more and more refined. I always have conversations with the effects supervisor up front, in prep.

I’m about to start a small film that you wouldn’t think there would be any effects work in. But nowadays, when you have a limited budget, you do turn towards effects work, because it’s so much cheaper to create something that, say, that might be on screen just for 30 seconds. If you wanted a crowd of 15,000 people, and it’s one wide shot and it’s just gone in a blink of an eye, you’re not going to bring in 15,000 extras.

b&a: In the podcast, you regularly mention storyboarding for all kinds of shots. Visual effects shots are usually treated as much more complex, expensive and need storyboarding and previs, say. I’ve always wanted to ask a DOP how heavily you perhaps get involved in previs, or want to get involved?

Roger Deakins: I’ve got to say, I don’t like previs. I’ve only done previs once. And that was for the opening sequence of Skyfall. And I was very involved, because Sam Mendes and I had a very specific construction for that sequence and the timing in mind. Sam had a very strong idea, but a very fixed idea, of what timing he wanted for the sequence to take. And he had music to go with it, so it had to be shot very much to this laid out plan. And a lot of it was being done by a second unit. That’s why we did the previs, just for Sam to make sure the sequence would work, and so he could see it, and so he could see the flow of it and the timing of it. But also to give it to the second unit and say, ‘Look, this is what we want. We don’t need anything else. We need this, and that’s what you’ve got to concentrate on.’

So, that was a very specific situation. I don’t remember any other previs really that we’ve actually used. Sometimes effects supervisors will do it for their own sake, but I don’t find it very useful. I’m kind of old fashioned. I like storyboards in the right circumstance, but only, say, line drawings. You just need them as a reference. And then maybe on the set, you throw them away. But I think doing a storyboard with a director is, like, you are exploring the script, in a way. It leads you to really concentrate on, ‘What do I want to see in this scene?’

b&a: Why do you think there are limitations with previs? Does it lock people in too much? Is that one of the challenges?

Roger Deakins: I think there’s a danger in that. Obviously, for Skyfall, we wanted it to be locked in. How many other films really work like that? I mean, 1917 was kind of a one-off in that we had to rehearse the sequences with the actors before we started building sets and digging trenches. Everything had to be built to fit the shot, if you like, not the other way around. But usually on a film, you have a set or a location, and there are certain things that are restrictions that actually help you in a way, that actually lead you to be more spontaneous on the day.

I’m very wary of working to a storyboard, or certainly to a previs. And also, if you have a previs, and everybody’s seeing it, and if the actors are seeing it, then suddenly it all becomes, ‘Oh, this is what we are doing.’ So it becomes more of a challenge to adapt or change or just work in a spontaneous way, I think. But each director’s different. Everybody works in slightly different ways. So I mean, it’s not to say one way is right and another way is wrong.

b&a: I guess previs is used a lot in different films, in different ways, and especially on big VFX films. But I always think, wouldn’t it be wonderful to always have the cinematographer involved at an early stage to maintain some sort of consistency in framing and composition? I suppose sometimes they are.

Roger Deakins: Yeah. Well, I’ve worked a lot in animation. And so often you can be discussing the look and the feel of a film, and then you see the shots laid out previs or animation, and you say, ‘What lens is this on?’ And you click on to see what lens is being used in the computer and you find it’s an 18mm, and it’s a close up of an actress or something! It drives me insane, because then suddenly it’s like, that goes all the way down the line, that actually you’re going to be shooting that shot on an 18. It gets kind of ingrained into the process and I find that really distracting.

b&a: You mentioned that animation involvement that you’ve had in the conversation at VIEW with Dean the other day. You came in to help on the some of these films, and you really had to question why some things were being done. I kind of like that you’ve disrupted that a little bit, Roger.

Roger Deakins: A little bit. The first time I was brought in on an animated film was for Wall-E. And that was really because they wanted a feel of a live action movie. I mean, animated films don’t tend to be made in cuts with wide shots and close-ups and mid shots. They weren’t really often constructed like that. Andrew Stanton, the director, wanted the feel of a live action film. So that’s how I started to get involved.

The funny thing is, you realize that a lot of the tools that were created for animation were almost trying to mimic the way cinematographers lit in the ’50s with hard light and cuts and multiple sources and traditional lighting. So, yeah, I kind of reacted a bit against that.

b&a: One of the things that you’ve talked about previously, especially for animated films, is that everything in the frame is lit and vivid and viewable, and you’ve said, ‘Well, why couldn’t that go into darkness or out of focus, like it really would?’

Roger Deakins: Yeah, that was a big challenge, especially when I started working at Dreamworks with Dean on the Dragon series, because we wanted to play the light and shade. I mean, that was the whole feel of the series, but it was hard to get that across at the beginning. I’ve had it on live action a number of times, where I lit a set, or the way we’ve shot a set, doesn’t see all of the set. And a production designer has sometimes said, ‘Well, can’t you go wider so you get my ceiling in?’ Or, ‘Can’t we light that corner of the room because there’s some lovely detail in the wall?’ And I’ve said, ‘Well, it’s not really about those elements.’ The shot might be a portrait shot of a character in the foreground. So you are not going to distract–I mean, there’s a whole different thing going on there, really. People obviously have different wish lists.

b&a: I’ve always been struck by those incredible lighting rigs used on films like Skyfall and 1917 for the fire shots. Obviously I know a little about those just from reading articles, but could you give a bit of insight into them? It’s something that people always mention when they talk about your work and the visual effects cross-over.

Roger Deakins: Well, that came from way, way previously, when I started doing smaller films. When I first started, I wanted to create firelight and would create firelight with a whole series of bulbs and put a chase on it so each bulb was moving differently. The first time I did that on a large feature film was actually with Sam Mendes on Jarhead, because we had to create this nighttime, nightmarish world, where the soldiers are underneath the oil fires in Kuwait.

We talked about how we were going to do it and there was some talk about doing it exterior at night. And I said, ‘Well, no, I really want to be able to create atmosphere and control it. So can we do it on stage? And they said, ‘Well, that’s a huge set. What are you going to do?’ And I said, ‘Well, if we just have sand, we can paint the wall of the stage to go on to infinity. And I’ll create the flame effects with the lamps.’ I had to show production a test of what I was talking about, so they’d be behind it. But I did just create these large columns of just household bulbs. They were mushroom bulbs, but just lit 360 and flickered, like it was an oil fire, but obviously to scale. And then we shot flames in the desert to replace my lighting rig, to look like the oil fire. So it was all done on stage and very highly controlled. And that was only possible because then you could shoot this, and those elements could be changed quite easily. You could replace a lamp with a real light source.

I took that approach again with Skyfall, where we had the burning Skyfall mansion and an extended sequence of Javier and Daniel, running away from Skyfall. And so, I said, ‘Well, I’ll do it with light on stage, and we’ll do it with atmosphere. And then we’ll replace the light with an element we shoot of our actual set burning.’ You gradually use that new technology to do something you wouldn’t be able to do another way.

The same then on 1917. Well, you’re not going to build a cathedral. And even if you did, if you built that cathedral as a set and then put gas pipes around it, like we did on Skyfall, you wouldn’t have the light that was going to light the sequence that we wanted, because it was the one shot. I needed a light source that could be on a whole dimmer system, not only flickering, but on a dimmer system. So certain lights could be on high when the camera was way, way away from what was the burning cathedral. And then it could all dim down as we got closer, so you had a decent balance in the exposure. It’s the same concept of having a little bar of 10 bulbs or six bulbs even, to do a fire effect, and you just expand it to your needs on a different challenge.

b&a: The results were amazing. I love your very matter-of-fact explanation of it, Roger. You know, ‘Well, that’s what we have to do to replicate reality. We just have to do that.’

Roger Deakins: Yeah. The scale of the lamp that we created, that John Higgins, the gaffer, and I created on that 1917 set, I mean, it was a huge light source. I’ve never done anything that large. But as I say, it was in essence the same as using a half a dozen little bulbs. You just scale it up.

b&a: Just to finish up, I was really excited to see more coming out about Byways, your book of photographs. How did that project come about?

Roger Deakins: I’ve always loved still photography. When I was in my 20s, I thought maybe that’s the direction I would go in. I wanted to be a photojournalist, I suppose. But as things worked out, I discovered documentary filmmaking and that led me to go to the National Film School. But I’ve always kept in touch with stills work, and I love it. It’s so different than working on a movie.

It’s interesting on the podcast, because we talked to a couple of the stills photographers that I’ve always admired, who I’d never met, and it was wonderful, Alex Webb and Harry Gruyaert. And each of them said they like working on stills, because each of them had worked in film a certain amount. And they said they didn’t like that. They each like to be by themselves and have total control over the image they’re doing.

I can understand that. That’s why I like taking stills myself. They’re my personal scribbles in a way. But I do love film. And I love the collaboration. So I’m different like that. I mean, I love being on a film set. I just love the camaraderie with people and the feeling that you’re all working together to the same end. I love that. But hey, wandering around with a stills camera and taking stills is —it’s very different for me. It’s my relaxation, if you like.

b&a: Did you enjoy that process of curating them, trying to choose the best ones for the book?

Roger Deakins: Yeah. I mean, there’s a few photographs where I still think, ‘Well, they would’ve been nice in there.’ But on the other hand, I don’t take a lot of photographs. I spend a lot of time trying to take photographs. But I can go days and not take a single frame. And then one day, I’ll go out, and I’ll find something. And I go, ‘Well, yeah.’ And then I’ll come back really happy, because I’ve got one photograph that I really like.

I don’t have a huge collection of images that I had to sift through. I tend to remember the ones I really like anyway. The most interesting thing was trying to get some sort of order and discipline to it, rather than it just being random. Damiani, the publishers, they were pretty wonderful. It was a wonderful relationship, just working on it with them. They were really supportive.

b&a: Do you have a go-to piece of kit for your stills photography? Or has it changed over the years, depending on where you are and what’s available?

Roger Deakins: For years, I was working with a Leica M6. And now I work with an M8, because 6 is film and 8s are digital. I like digital, I must say. Well, I did like working in a darkroom. I always liked that process, but the change means I don’t have to develop the negative, which I always did. I never took my negative to anyone else. I always did all of the processing myself, and I do find it, well, I find it similar in the film world. I really like it at the end of the day, when I’m on a film, to know that’s what we’ve got. You can watch it back on the monitor. You know that’s what you’ve shot during the day. And the director could be happy or not, but he’ll know what the day was like. And I feel that’s the same, taking still photographs. I just like to know I’ve got that shot or not. More often than not, I haven’t got the shot, but that’s all right. At least I know before the end of the day.

b&a: Well, I can’t wait to see the book. Roger, it’s been such a pleasure talking to you about your work and the podcast. Thank you for doing it. Really appreciate it.

Roger Deakins: It’s a pleasure. Thanks very much.