Shooting models sideways, making Tim Robbins act in reverse, and the movies where the same miniatures made surprise reappearances.

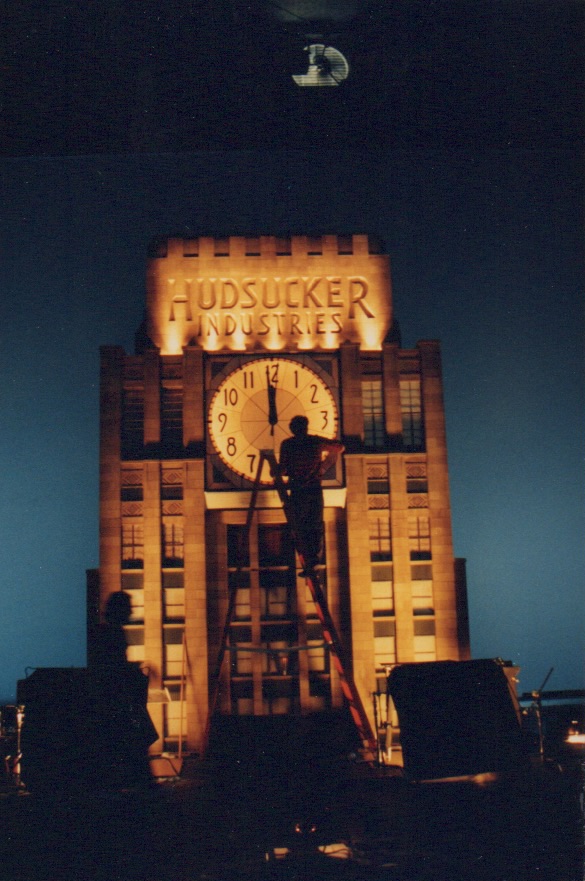

Now 25 years old, the Coen brothers’ The Hudsucker Proxy was one of those ’90s films that featured exquisite miniature buildings, carefully planned motion control photography, and meticulous digital compositing.

Drawing from the work of production designer Dennis Gassner and cinematographer Roger Deakins, the visual effects team crafted a raft of ‘mythical’ New York-type landscape shots that featured heavily in the story, not least of which was for a number of scenes of characters leaping and falling down the buildings’ long façades.

To celebrate The Hudsucker Proxy’s quarter-century anniversary, befores & afters asked visual effects supervisor Michael McAlister and miniature effects supervisor Mark Stetson about their experiences on the film, including filming models lying down, what it took to make great miniatures back then and where to spot the buildings in other subsequent films.

Michael McAlister: The Coen brothers were the most visionary directors I’ve worked for, and it was my challenge and my responsibility to figure out what they wanted, and then deliver it. Hudsucker is one of my favorite movies that I’ve worked on, and I’ve often said in interviews that it’s the only movie that I’ve worked on that I wouldn’t change one frame of film under my department’s domain. And I attribute that to their visionary capabilities and the fact that they had absolute creative autonomy over their movies.

Mark Stetson: We built the buildings in our shop – Stetson Visual Services – in LA and then shipped them all to Wilmington, North Carolina, where the film was being shot. We were on a good-sized shooting stage out there, but when they were doubled in height – they were 45 story buildings when you’re looking straight at them, and 90 story buildings when you were looking down them – it made it difficult for the motion control rigs to shoot them and for the stages to simply erect them. So they were laid over on their sides, and we suspended one side of the street from the ceiling. And then put legs onto the floor for the other side of the street with the doubled heights of the buildings.

Michael McAlister: The Coens had a vision of a mythical city. I believe they were talking about a mythical New York, where there was a high concentration of tall skyscrapers in a confined area. In fact, we borrowed from the Chrysler Building and different real buildings as inspiration for designing and building the miniatures. But there was no cityscape anywhere in the planet, at that time anyway, that even got close to what the Coen brothers had envisioned as this mythical city. So that’s why they had to be miniatures.

Michael McAlister: The trick with miniatures and getting them to look photoreal has to do with the level of detail in the paint jobs on them. Ron Gress, for example, was spectacular at being able to put paint jobs on the buildings, that included things like running stains from rust and just the various ageing from smoky atmospheres, or smog, or dirty windows. It’s just incredible what they knew how to do with airbrushes and other kinds of medium to make these look photoreal when you’re standing three feet away from them.

Mark Stetson: Having a good painter like Renee Rabache or Ron Gress (both pictured here) was crucial. And they were two of the best painters in the business as far I was concerned. I can’t say enough about how talented they were in terms of applying finishes. And doing it in a clever way, the way a matte painter does, sort of by ‘indication’ and not being too technically accurate, but rather being subjectively accurate, would be one way to put it, or just making sure that the emotion of a scene is there to be seen.

Mark Stetson: We were doing mostly things out of either etched brass, or cast out of urethane for all the detail work. Nowadays, so much is done with 3D printing and laser cutting that you can do a much better job now than you could back then, and do it faster. But our key things were finding a good team of miniature sculptors, and we had them. Back then it was a lot of repetitive mold-making and casting of parts. And we really just had to commit to a lot of repetitive rote work like that.

Michael McAlister: For the scenes where we needed to get the background plates for the actors that were jumping out the window and falling toward the ground, we positioned those horizontally, rather than vertically, because of the camera systems that were available then. We were using motion control crane cameras for shooting miniatures at the time, but they weren’t able to get high enough to start up at the top of the building to make your way down to the ground. So it was decided that we would configure them with certain buildings laying on the floor, and then the other side of street, we’re building suspended from the grid on the sound stages. The camera was basically running parallel to the ground, and that allowed us to shoot them that way.

Michael McAlister: When it came to shooting the images of Tim Robbins, and Charles Durning, we hung them on wires from the grid of the soundstage and we used a motorized dolly that we had live action cameras on. We rigged things so that we would shoot the scene in reverse, because the idea was in the case of, especially, Tim Robbins, where he’s falling, and falling, and falling, and all of a sudden comes to a stop, when time stops, we wanted to be able to film as if we were approaching Tim Robbins on the soundstage at free fall speeds. But because the camera equipment we were using, we couldn’t guarantee it was going to stop on a dime and not just crash into Tim.

Michael McAlister: We ended up filming those falling scenes in reverse, so the camera would start right in his face. Tim was required to act in reverse, as if he was coming to a sudden stop, and he did a great job on it. He actually had fun with it. But we would set up the shot and roll the camera, and he would mimic as if he’s coming to a stop with his arms flailing, and his head bobbing. And then the camera would very quickly, as quickly as it could go, would pull away from him all the way to the other end of the soundstage, and then of course just run the film backwards when we composited it. And of course, that was all shot against a bluescreen. The composites were thanks to the talents of CFC and Janek Sirrs. With any kind of bluescreen work, the lighting on the different elements is critical to the success. And I had learned a lot about good bluescreen lighting from my mentor, Dennis Muren, and years of work at ILM.

Mark Stetson: Models are a bit of a lost art, or are becoming a bit of a lost art. Atmosphere was key. Lens matching, and making sure that you’re scaling the camera motions, that was really key. And building miniatures to a scale that you could shoot them, to keep them in the style of the film, that was really key. And sometimes the fact that you’re committing to miniatures for your visual effects, helps to to establish a style, and set a style. We were, in those years, really pushing the design and capabilities of motion control systems. I think back in the mid ’90s, the best motion control work ever was done. It had to do with writing camera moves in a clever way, and editing the moves, editing the curves to mimic live action cameras. We got into shooting miniatures in that period, making digital models of the camera rigs that we were using and putting them into digital previs, so that we could see what the cameras were really gonna be able to do, and make previs more accurate. (In this photo: effects director of photography Pat Turner.)

Mark Stetson: There’s some fun stories from that film. I remember Ian Hunter, our chief modelmaker, had a little sign on the model shop. I think it said, ‘Hudsucker Industries, Department of Miniaturization.’ And ‘Department of Miniaturization’ was in progressively smaller type. Also, the fun thing about that set of buildings is they had such a life to them. They went back into the Universal Studios prop shop, or the scene dock, and they were in many movies. At the end of that show, the production manager asked if we wanted the buildings back for $10,000. And I just looked at that, and thought, ‘Oh, this is just a giant storage problem. I have no place to put them.’ And said, ‘No.’ And then a few months later, I was bidding against somebody else to use those buildings again for The Shadow. And the other show was Baby’s Day Out, and they ended up with the buildings. And so, I didn’t have access to my own buildings! And then I was in the same position on Fifth Element, and Godzilla was using them then I think. Every time I wanted to try to get them back to use them again, I couldn’t. We kept building more and more buildings instead. I guess we did get them back. I think we did get them back for The Shadow, but we had to wait until after Baby’s Day Out was done with them.

Images courtesy Michael McAlister.

For more on the miniatures from The Hudsucker Proxy, including where the models found future homes, check out this extended scene from Berton Pierce’s Sense of Scale documentary.

This is one of the Coens’ best movies and the VFX shots look great, especially for the time. I love a good comedy where VFX just helps tell the story rather than big VFX movies that try to squeeze some crappy jokes in. This is the sweet spot.

Thanks for your article!

Thanks so much, Benjamin. I love this film, too.