The intensive previs process on ‘The Phantom Menace’

Planning shots out before you shoot them for real is not a new concept, and it also wasn’t necessarily new around the time George Lucas set out to make Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace (which is currently celebrating its 20th anniversary), but utilizing then-new digital tools to help craft video animatics was a large part of making the film, and lay the groundwork for a whole-hearted adoption of previs on the subsequent prequels and other films, even spawning a number of individual previs companies itself.

David Dozoretz was in the ILM art department before The Phantom Menace began taking shape, and through a number of somewhat happy coincidences, motivation and ability, he would find himself the trilogy’s first digital artist, embedded at Skywalker Ranch knocking out previs scenes for the film. Here, in his own words, Dozoretz – who would later found Persistence of Vision (POV) Digital Entertainment – lays out Episode I’s previs history for befores & afters.

‘You were not allowed to animate anything’

David Dozoretz (pre-visualization effects supervisor, The Phantom Menace): It was, I think, 1994. Though quite young, I was working in the ILM art department and I had done a couple of little things with computers. The ironic thing was that computers at that time were not really the domain of the art department. They used a little bit of Photoshop, but they had this rule that you were not allowed to animate anything. Everything in the art department had to be still art.

I remember even at one point I wanted to get modelling software – the best 3D modeling tool back then was Form-Z – and it was something like $1,100. Everything that was over $1,000 had to be approved by the head of the company. But when asked, she said, ‘Absolutely not, this is a computer modeling program and you’re in the art department, this is the purview of the computer graphics department, so no, you can’t have it.’

It’s an example of how, at one point, even the forward thinking ILM didn’t quite understand how computers would be fully utilized in the filmmaking process. By the way, I ended up finding somebody who would sell it to me in two $550 purchase orders, so I got the software anyway.

So then [Phantom Menace visual effects supervisor] John Knoll knew I was a little bit of a computer nerd. In fact, I was the computer nerd who could speak a little bit of the art world and a little bit of an art nerd who could speak to the computer graphics world, so I helped to bridge those two departments, which were very fairly separate.

Anyway, John Knoll came to me and said prior to the first Mission: Impossible movie, ‘I need to help the producers show the studio what this scene will look like and storyboards aren’t quite cutting it because it’s such a dynamic scene with 3D camera moves, and absolutely rushing speed.’ It was the scene where they’re on the TGV, the French high speed train… a wild, almost ludicrous scene. John said, ‘Can you use this software?’ which was Electric Image, ‘and do animatics?’. Well, when John asks you to do something, you say yes.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]I went from no textures, no shadows, no motion blur to the podrace previs, which had all three.[/perfectpullquote]

Animatics was what we called it back then because we were editing storyboards together a little bit and that’s what they were called. And, of course, George famously re-edited shots from Tora, Tora, Tora for the first Star Wars movie, but that was literally splicing together film. John said, ‘Let’s do this for Mission: Impossible,’ but with very rough computer animation. And I worked on it for like two months and I did a version of everything that was storyboarded, and it was by today’s standards horrible. Absolutely awful. It was clunky and the lack of textures made it read slow and the characters had basically no faces. It was just camera playblasts, no real rendering.

But what it did do was tell a story and that was the ballgame. And I got it done very quickly despite being the only one working on it. We proved someone could previsualize an entire movie action scene. Paramount ended up having Tom Cruise make for Mission: Impossible so the process was a success.

I also got to do some previsualization on the Star Wars Special Editions. One of the things George wanted to do was add Dewbacks – the large lizards – to shots where the stormtroopers are searching the desert for the droids on Tatooine. He was disappointed when he originally made the movie that the searching didn’t seem intensive enough. Everybody was trying to figure out what these new changes would look like so I did previs of that.

That was when I was still at ILM, that was between Mission: Impossible and being hired on The Phantom Menace. It was both a test for him to see how the technology was improving, and, I think, his first exposure to digital pre-vis.

‘George has decided to start up Star Wars again…’

Then one day we’re all in the art department and the head of ILM comes to the art department and says, ‘Listen, George has decided to start up Star Wars again.’ Remember at the time it was only the three original movies and that infamous Christmas special, so this is what everybody wanted, it was pretty much what got them in the business.

She continued, ‘George thinks the technology has gotten to the point where he can visualize what he wants it to be, can make the films he wants to make. I just want to let you known you are all welcome to apply for a job up at Skywalker Ranch. You won’t be penalized here at ILM if you apply for a job up at our sister company, Lucasfilm.’

And we looked around the room and all of us were playing it so cool with each other. We were like, ‘Yeah, maybe, maybe not, I don’t know, we’ll see, I got things to do.’ But that night everybody was there until 1:00 in the morning working on their portfolios. We all wanted in. And I had such a different portfolio because mine was a videotape. Everybody else had fantastic art – it was people like Doug Chiang, Ian McCaig and Terryl Whitlatch, TyRuben Ellingson – brilliant, brilliant artists, world-class artists.

And all I had was a VHS tape with the animatic that I did for Mission: Impossible and a few for the Star Wars Special Editions. I don’t think it was ever genuinely looked at, to be honest – George hired two people first, Doug Chiang and Terryl Whitlatch. And in hiring those two people, George started doing character designs, and set designs, and world designs. It was the Ralph McQuarrie phase.

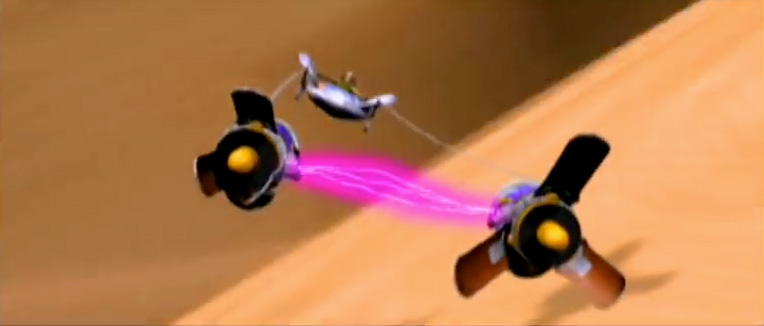

But at one point George was telling Doug and the producer Rick McCallum about his ideas for something called the ‘podrace’, a big action scene in the middle of the movie, and it was basically like the Ben-Hur chariot race. Well, Doug and Rick knew storyboards weren’t going to be enough for this. They did storyboard it anyway and it was something like 2,000 panels, but even before that they thought it needed something more.

At that point, I think Doug showed my animatic for Mission: Impossible to Rick. And Rick showed it to George. He’s always up for using new technology in his filmmaking process, so that’s when I got the phone call, obviously, a really great phone call.

Now…this…is…podracing

So I was the third artist hired and the first computer artist hired. It was just so lucky because this was the time when computer animation was really having its birth. My first and main responsibility was the podrace. It was a big evolution from the Mission: Impossible stuff that was so rough. This got better both because my skills got better, and because we used more and better tools.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The version in the film is 9 and a half minutes but there existed at one point in previs a 25 minute version, if you can believe that.[/perfectpullquote]

One example: at that time, we had these sort of unwritten rules for previs, and the most important goal of these rules was, don’t make it too fancy. Don’t try and take on doing the finals, don’t try and be the final computer graphics department or animators, keep it incredibly rough so that the people looking at it don’t judge it for the wrong things – which is completely legitimate – and so that you can go so fast that it’s efficient to be able to do this at a design level.

Really the whole point of previsualization is to throw stuff out so now we know what does and doesn’t work. In order to follow those rules that we had created on the fly for the Mission: Impossible sequence, we said, ‘Okay no textures, no shadows, no motion blur.’ Those were three things that, with the computer graphics tools available at that time, took a lot of memory or slowed things down a lot. But for the podrace, we really need to solve the problem of communicating the speed and motion.

So, how do you communicate speed if there’s motion blur? Well, there’s detail of things rushing by camera like the texture of the sand on the ground that the podracers are floating over. So now you want to do good textures because it shows how things are moving in a camera better than a flat color. And how do you show that these things are floating above the ground and how far away they are in space? Shadows. So now we’re doing that in previs. And nothing says speed of a object whizzing past camera or or a camera panning quickly quite like a lot of motion blur. So I immediately went from no textures, no shadows, no motion blur to the podrace previs, which had all three. I immediately broke the first three rules that we set for previs.

And now I was rendering everything, too. Granted, it was small renders – NTSC video. But no more playblasts as the final product. George is fantastic in the way that he knows exactly what parts about a tool are worth looking at so he never looked at previs and said, ‘That doesn’t look like what I imagined the final shot to look like.’ He got exactly the point, like he always does. And I guess that’s why so much of the current filmmaking process – with digital pre-production, digital cameras, and digital non-linear editing – so much of it we owe to George. He always knows how to use a technology the right way, no matter how small.

Getting stuck into the previs

I remember when I got the very, very, very, very first shot done there was this little moment were Rick, the producer, high-fived me and said that’s the first shot ever done for the prequels. It was within a week of my being hired…just a podracer with nobody in it that shot past camera. But for the first time it was something that went from George’s imagination to something that other people could see and discuss.

I probably had a year or two by myself first and then we started to get more sophisticated with the models because we wanted it to look even more like what Doug’s great design team was doing. And I was swamped. So I brought in a modeler, Alex Lindsay, and then a few other previs artists. We worked on dozens of sequences – mostly ones without the main digital character, if you know who I mean.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]That made George ecstatic. He had never before got to iterate that quickly.[/perfectpullquote]

But the podrace was big. I had at one point a 25 minute version of it. The version that’s in the film is about 9 and a half minutes but there existed at one point in previs a 25 minute version if you can believe that. The one thing that the previs couldn’t really do at that point that storyboards could was character work. George wanted the bad guy in the race, Sebulba, to drive the story. So Robert Barnes was one of the artists up there and he made rough foam core puppets. Robert and Ben Burtt, the sound designer and editor, shot these puppets on greenscreen and we composited that on top of backgrounds into the previs. So we got some character work after all.

It was a mixed-media thing, really. There were a couple of storyboards here and there, certainly I based a lot of my work on storyboards, but a lot of the time George would just say, ‘Try this or try that.’ And it was a very, very rough, very fast iterative process, I was lucky to be able to work with the editors, Martin Smith and Ben Burtt to visualize all this stuff. We were just learning as we were going on.

I thought at that time that I was the only one really doing CG previs, but I’ve since learned there were a couple of other people doing a little bit of previs. There was a wireframe shot done for a movie called The Boy Who Could Fly, and I think Colin Green might have done a some previs for Demolition Man. So it would be wrong to say I was the only one doing previs. But I do believe it would be accurate to say that I was doing it on a scale that nobody had before.

Once we were done with the podrace, which was never really ‘finished’, I started doing previs for other sequences including the end battles. We ended up at one point even going down to ILM and using their brand-new motion capture stage to get some character movements for some of the end battle stuff. So we were putting motion capture onto previs, that early. I believe if I remember correctly it took two weeks from the time that we captured the motion on the stage to the time that it was processed, and I could see it in the computer just as dots moving around.

Tools of the trade

In terms of tools for the previs, I was using Electric Image, primarily. Maya didn’t yet exist and the producer didn’t want to go out and buy a $65,000 Silicon Graphics IRIS workstation for me to work on in order to use Alias or Softimage at the time. I actually eventually got one because I needed it for the motion capture stuff running in Softimage. But I started only using Electric Image on little 68k Macintoshes, saving stuff to five gigabyte Jazz drives and Seaquest drives – this is ancient history.

I was modelling in Form-Z. We were doing compositing work in After Effects, which at that time had not yet been bought by Adobe – it was CoSA After Effects – and of course Photoshop version 1 or 1.5. Windows NT had just come out so we were like debating whether or not we wanted to switch to Windows NT because it was much more stable at the time than the Mac. I can’t tell you how many times I was sitting there waiting for reboots back then, it was ludicrous.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]I worked until the middle of the night for years, and I loved it, it was a great experience.[/perfectpullquote]

And CRT monitors that weighed 80 pounds that we had to move around all the time as the art department grew and shrank. It was some pretty antiquated stuff. But we were sitting there in the third floor of George Lucas’s Skywalker Ranch – the main house – and we were working on Star Wars. And at that point it was just the idea creation stage. So it was a really fun experience.

When Episode II came around and it was time to start on that we were able to do much more sophisticated things. We switched to Windows NT machines, we switched to Maya, and I had a team of 10 people. We were edited in the Avid. And what I did was a post-mortem at the end of Phantom Menace where I said, ‘Okay, what can I do better for the second movie?’ I looked over in the corner and I saw that I had three feet tall stacks of yellow legal pads with all of my notes from George, the editors, and the art supervisors,. I thought, ‘That is crazy.’

So I worked with one of the IT staff at Lucasfilm and created a Filemaker database that for shot and version tracking. Although the movie is only 2,000 or so shots, with all the different versions we previs’d, we had over 10,000 records in the database. Every artist had a dynamic to-do list, every note was quickly accessible, and I always had an overview of where we were in the schedule.

One day something happened that really illustrated how well it worked. Wi-Fi was just coming out then, we had it in the basement of the Skywalker Ranch main house where the editors were. And I would be able to sit in the edit room with George and the editor. One day, George asked for a change to a shot – something like, ‘The spaceship needs to come from over there more on screen right.’ I typed that into the database, hit enter, and it of course updated the database. Upstairs – three floors above me – the artist who shot that was would get a notification: ‘There’s a note for your shot.’ That artist would make the change, and because it’s previs, did a quick playblast and the shot was done and back in the Avid before I had left that meeting. That made George ecstatic. He had never before got to iterate that quickly.

That was just a production management thing but it really helped make the process a lot smoother. On an artistic and technical side, we did end up starting to add dynamics to things. Once we got everything in Maya, we could push assets back and forth with ILM. So for Episode II the quality of the previs really went up a notch and that continued.

I worked on Phantom Menace for about four and a half years. It cost about $65 to have a cold pizza delivered in the middle of the night to Skywalker Ranch, but that’s what I did – I worked until the middle of the night for years, and I loved it, it was a great experience.

Explore more of our in-depth ‘The Phantom Menace’ 20th anniversary coverage during #phantommenaceweek .