They crafted environments, water, snow, rain, explosions and many other effects for the Guillermo del Toro film.

In this fourth behind the scenes look at the making of Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio at befores & afters, we now center in on the visual effects work overseen by VFX supervisor Aaron Weintraub.

Weintraub, who hails from MPC (formerly Mr. X), led a team that would enhance the practical stop-motion photography with environment extensions, digital weather elements, explosions, water and many other visual effects to help tell the Pinocchio story.

Here he chats to befores & afters about the process, and shares many behind the scenes images showcasing the visual effects.

b&a: I have a feeling a lot of audience members would not think there are many visual effects in Pinocchio.

Aaron Weintraub: If we’ve done our job correctly, the audience should feel like it just slots right in there, and they don’t think about it. In live action, it’s easier to do that because they know what can be photographed and why, and they know what the world looks like. It’s like if you shot Toronto for New York and we had to replace all the skylines and it just looks like New York in the movie, they would never think about it, and it wouldn’t ever be an issue.

Obviously, here, we knew we couldn’t shoot everything practically, even though that was the mantra. It was like, ‘If we can shoot it, if there’s a way to build this or fabricate it, we’re going to do it practically.’ And then the flip side of that as well, if we can’t, then it’s, ‘Go to visual effects. They’re going to do it.’

I mean, stop-motion is visual effects. So the whole movie is a big trick of making things move by shooting it a frame at a time. That’s what visual effects was. Meanwhile, every shot had rigs and wires and clean-up and face chatter. We knew going in that that was going to be a thing. And even some simple comps, just shooting things in layers, that was like the bread and butter sort of work that we knew had to be done. They did have an in-house team that handled a lot of shots, say a drama shot where it was a rig that needed to be removed.

For MPC, however, the main thing on the plate for us was effects simulations. So all the water, all the fire explosions, snow, rain, all that kind of work, and there are a few big environments that we did. For example, the interior of the Dogfish is a digital environment. The interior of Limbo is a digital environment. Establishing the church plaza and looking out the door when they’re inside the church is a digital environment. All the skies in the film are digital, too.

b&a: Tell me more about Limbo.

Aaron Weintraub: It’s a sandy floor. There’s a plinth that the death character, the sphinx, is standing on. And then the background is surrounded by these shelves that are filled with hourglasses. Originally that was planned to be practical. They were going to build that. We were still going to do the dome–when you look up, there’s this ceiling planetarium design dome with animated elements moving around.

We were always going to do that, but the shelves were supposed to be laser cut acrylic set pieces where they would carve in the hourglasses and play in the background out of focus. Then COVID hit and all the acrylic got snapped up to build sneeze guards for banks. There was a run on the material, and they couldn’t do it, and that went digital.

b&a: What about the actual sinking sand?

Aaron Weintraub: The quick sand is practical. All the critical contact when the characters are touching the floor on the sand and on the ground, and in the Dogfish too. Where they stand, they built little islands of ground.

b&a: Let’s talk about the simulations–I found the water to have a very, very interesting look. I don’t quite know how to describe it, but it didn’t really look like sim’d water. It looked like something else.

Aaron Weintraub: That’s very, very intentional. There was a lot of creative back and forth and wedging out different parameters to find the look. But the idea was, the guiding principle with all the effects going in, was that this world is being designed, and it’s very much an animated feature. Everything that’s being put in front of the camera had to be, was thought of, sketched out, designed, built, manufactured. Everything was there on purpose. And it has a very specific look. And that’s the look that they wanted for the film.

It was an acknowledgement that it’s a world of puppets. It’s a movie about puppets, about a puppet being pulled with puppets. So it’s very meta on that level, but all these design rules found their way into the effects. Our goal was that all the effects, especially the water and the fire, had to fit into that world seamlessly. It had to appear as if they could have shot it, that’s what it would’ve looked like.

b&a: I feel like it depended on the sequence a little, if it was underwater or waves lapping at the beach. It was more frothy and see through than you might normally do for live action water.

Aaron Weintraub: The froth layer was an extra layer that was added on top that was always meant to be this kind of crystalline structure, like little glass beads or glass shards or chunks of ice together.

The idea was that it was a static surface. It didn’t flow. It all started with a normal Houdini FLIP water simulation, and you need that to get the interaction on the lapping, especially when characters are interacting with it. Then we would take that simulation and post process it to remove any kind of lateral flowing motion so it became a static rubber sheet. The idea is that then it only goes up and down. It has wave crests in it, but they don’t go anywhere. It feels like an ocean made out of static solid rubber that waves around up and down, but the peaks don’t actually rise and flow.

b&a: What about rain? We might think of this as relatively easy to do in visual effects, but here I guess you had to match to a ‘stop-motion look’. How did you approach it?

Aaron Weintraub: There was a look set in the practical stop-motion where they would do rain that interacted with the characters. In the scene where Cricket is leaning out a tree trunk hole when Geppetto is cutting down the tree, there are drops running down the tree trunk. There are drops kind of pooling up on his elbow and then dropping off. These were stop-motion.

We built the rain simulation. We actually built these drops modeled after what they did with the glycerin on set that they used for their rain drops. It had the same surface qualities and refraction properties. It stretched the same way. The idea was that it just became a seamless addition to the scene.

Guillermo would always ask for more interaction. He’d say, ‘Okay. This shot’s great. We just need three more drops. Have one hit his hat, have one hit here, and more drops dripping off his umbrella.’ The idea was making it all feel like, if they had the time, they would’ve put thousands of little drops on wires and put them in there and then moved them all and then moved them all again and shot it.

b&a: You mentioned you also simulated fire. What different kinds were there?

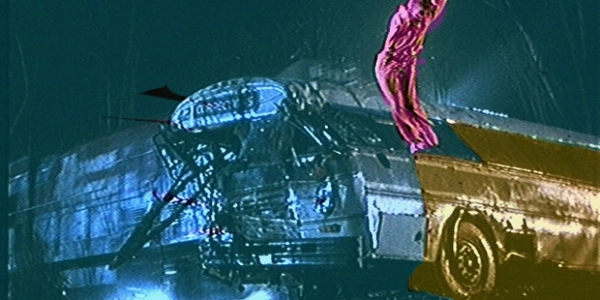

Aaron Weintraub: There’s so much stuff that you would just never think of. I mean, there’s fire in the explosion at the church and then the subsequent burning of it. There’s the fireplace in Geppetto’s house that Pinocchio puts his feet in. There’s the bonfire at the end when he is on the cross. There’s the explosion at the youth camp.

We knew we were going to have to do that digitally, although [animation supervisor] Brian Hansen did a practical test early on in pre-production where he took pieces of cheesecloth, wrapped them in armature wire and animated them flickering around. The DOP, Frank Passingham, set up a whole lighting system with flickering lights called the ‘Time Machine’. It was like gels on a wheel that were motion controlled and could be repeated. You’d have the flickering as a repeatable pass that you could do for every frame.

The fireplace fire was not a pyro sim at all. It was a cloth sim emulating this cheesecloth test. We actually modeled pieces of cloth, simulated it flickering around, and lit it and brought it into Nuke to achieve the look.

For explosions–typically in stop-motion, explosions are done with cotton, just big balls of cotton. So we emulated that. It was the same thing with the clouds. If you frame by frame through it, there’s little fibers, and it’s all meant to look like real cotton textured material, especially the clouds.

b&a: In terms of rig removal, what were the very specific challenges there?

Aaron Weintraub: The beauty of stop-motion, and this was one of these crazy aha moments, is that for every shot you can shoot multiple passes, and you can repeat everything. So you do your hero take or you map out your hero take and you know where the rigs are going to be. It’s like, ‘Okay, I’m going to need a clean plate for there. I need a clean plate over there.’ Your hero pass probably has a big chunk of the floor missing because that’s where the animator is popping in and out of every frame. So we have all these trap doors and half of the set is missing just for animator access. And then you do the hero take, then get rid of the puppets, put all the set back together, run it again, and that’s your clean plate.

The beauty is that you know everything is usually going to line up. Some problems did come up, these little things that you never thought you’d have to worry about. Especially, because it takes so long, day to day a set might shift slightly just because of moisture in the studio, so the tables that they’re shooting on, especially over a weekend. So splitting a shot from Friday to a Monday, you come back three days later, and things have just shifted enough to make it a bit of a nightmare or a headache for the paint and rig removal.

You always have to watch out for shadows, too, it’s not just the characters, it’s not just the rigs. It’s the shadows that the rigs cast on things. But one of the really cool things that doesn’t ever happen in live action is you can shoot passes for mattes. So you always get a hero greenscreen pass where you could kind of silhouette, that is, turn off the hero lighting on the characters, so they’re just black. You turn off the lighting on just the greenscreen and then run that pass again. And then you get your matte almost for free. The rigs get in the way of all that, but it’s still really, really handy to have. ‘Motion control actors’ how we thought about it.

b&a: They were shooting essentially what can be described as partial sets often with greenscreen backing or bluescreen backing or no backing. How did you generally approach set extensions?

Aaron Weintraub: Well, as I mentioned we did all the skies as well. They were all based on or inspired by classical artists and artwork. There are actual brush strokes in there. The skies were designed as pieces of fine art that would play as the background.

The Dogfish was our biggest environment. There was nothing built for that other than just some land where the characters interacted and half a practical lighthouse. Guillermo always described the lighting in there too as a placental light where there’s light kind of leaking in from the outside. You get a red subsurface scattering on the walls that silhouette the ribs.

b&a: One other thing with stop-motion characters in other films is that many times they use visual effects to hide head replacement and face replacement seams and fingerprints and other things. I don’t feel like you needed to do that here, is that right?

Aaron Weintraub: This was a debate throughout, which was the charm debate. It was like how much charm do we want? And you’d have these artifacts and you watch the take in dailies, and then Brian Hansen would always ask, ‘Is that charming or do we want to fix that?’ There’s a certain amount that we left in just to illustrate that it gives it that handcrafted feel.

Pinocchio was the only rapid prototype / 3D printed character. All the other ones are more traditional stop-motion puppets where there’s actual joints in the mouth and the faces and the eyes, and the puppets were controllable and animatable that way.

Pinnochio’s head replacements did result in some face chatter and that was a thing that was cleaned up. However, it was, ‘Don’t remove it completely. Bring back some of it,’ because it’s charming.

b&a: What kind of 3D builds did you ultimately have to do?

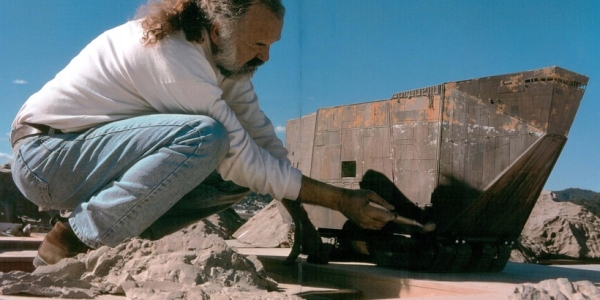

Aaron Weintraub: We scanned everything. Every set, prop, every character. We mainly we used them for environment extensions. For the puppets, we used them for all the interactions of snow, water, rain. All of the characters were match moved for this.

Also, I think going in, people were maybe worried about us having to do a digital puppet. The thought was that maybe it would be said, “Oh, we don’t like the performance and we want to change this performance. Can we just do a shot with a CG Pinocchio where he goes and talks, and we change his line and we change his action?’ But no, they fully committed once they did a take and they liked it. So there wasn’t much of that at all.

There were some crowd scenes. Not hero animation, but a lot of the fascists work, a lot of work in the carnival and extra kids. We had full digi-doubles that matched. They built a few puppets, and then we built more and animated them in the capture the flag sequence in the youth camp. There’s digital kids running around in the background.

b&a: Was there one sequence, one shot, that you felt was over and above harder to pull off in terms of visual effects?

Aaron Weintraub: The stuff we were most worried about was the heavy water interaction. There is a shot where you’re inside the Dogfish mouth looking out and Pinocchio’s on the tooth, and we pull back and you see the whole mouth there. The water was rushing in, interacting with teeth, interacting with the mines, there’s flashing everywhere. I was nervous about that one.

Another thing we had to figure out how to deal with was the stop-motion shooting on 2s or the varying frame rates. It wasn’t always on 2s, but they would change it up as they needed for the motion to feel smooth. But when you’re doing a Houdini simulation, it is hard to change these things. We would rotomate all the puppets and anything that interacted with the water. The first thing we do, if we had the Dogfish or Pinocchio who had to interact with the water, we had full digital models that we would rotomate precisely, so we had full 3D geometry versions of them.

Then we would stimulate the water around that and then just composite the water back with the original puppets. But when you have your puppet moving and then stops and it moves and stops, moves and stops, the simulations don’t love that because they’re trying to be smooth. They’re trying to anticipate what the motion is. So we just had to find ways of working around that, doing in-betweens and finding different ways to have the simulations not freak out when something stops every other frame.