Flubber!

Twenty-five years ago this week, the film release schedule was awash with CG and VFX-heavy projects. Industrial Light & Magic, which had had a hand of course in a number of these, further demonstrated a diverse visual effects skill set with its work on Flubber.

Brand new challenges for the studio came in the form of Flubber itself, which had to be both a transforming piece of sticky goo and a character with major personality, while also being reflective and translucent. ILM’s artists solved these issues in several ways, including taking advantage of Softimage’s MetaClay tools.

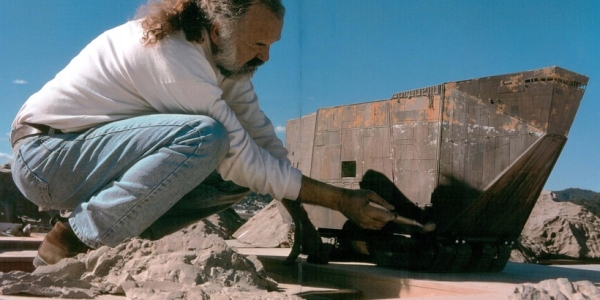

Philip Edward Alexy was a lead technical animator at ILM on Flubber, and he shared some memories of the show with vfxblog (this article is a re-post). The show was overseen by visual effects supervisor Peter Crosman, and by VFX supervisors Tom Bertino and Sandy Karpman at ILM. Alexy also shares some rare crew shots and behind the scenes stills from during production.

b&a: In terms of Flubber’s performance, what were some of the early discussions about how you would be creating a personality and movement for character like this?

Philip Alexy: In the beginning, it was very much: ‘OK, We have to make this goo that can do all these things … um… how exactly do we do that?’ Before I was brought into the production, there were conversations about setting up something similar to the water tentacle from The Abyss or the T-1000 from Terminator 2. However, since the script called for replicating flubbers that were also supposed to then immediately morph into other shapes, this was considered unpractical.

However, Jeff Light, a technical director with animation expertise was playing around with a modelling tool in Softimage 3|D called MetaClay. It had the ability to create a mesh based upon placed spheres of influence, meant only to be used to build up masses of this CG clay into a model, and then use the resulting mesh as a reference. The breakthrough came when I took over Jeff’s research and applied it to something animated.

Now this let us create and animate flubber in more a classical-animation ‘squash-and-stretch’ methodology that also had the quality of something that could exist in the real world. Flubber then became something along the lines of a true ‘cartoon’ character; able to visually express its emotional state with its whole body. The clients, after we showed them some animation tests, were stunned and very excited.

b&a: Because Flubber was so much more flexible than a traditional CG character, what was the approach to rigging the character?

Philip Alexy: Rigging had to be rethought for Flubber. Traditional methods of skinning and bone structure were replaced with spline spine deformation rigs with control points for bend, stretch, and up-vectors.

On the technical side, since the vertex counts for the model mesh were never constant, the technical geniuses at ILM were able to use proprietary ‘blobbies’ that took the baked variable mesh and filled it like a rubber balloon with thousands upon thousands of these blobs. The resulting mass DID have, after evaluation, a set vertex count, allowing for motion blur and other rending processes that simply did not work with MetaClay.

ILM did use, for one of the first times in film production, mental ray, which gave physically-accurate refractions through the flubber (unlike RenderMan at the time, which ‘faked’ it). But it was very computationally-intensive so it was used sparingly and only for hero flubbers. I should also mention that mental ray was the first renderer I had heard of at that time that used true ray-tracing for refractions.

b&a: What went into the shot that saw Flubber being scared by the flash? Why was this one particularly tricky?

Philip Alexy: The scare flubber – that shot took a couple months only because not only did it have to be animated, but look good enough for the polaroid picture still that in in the film. That meant it had to be a smooth mesh with several different ‘tentacles’ AND be able to morph into that shape from the base blob flubber.

I did the same trick with this shot as the puppy flubber: hiding the scare rig inside of the blob. The mesh vertex count was enormous and took several hours per frame to render. Not only that, but the file in Softimage was so dense, it took about a minute just to click forward one frame – while I was animating.

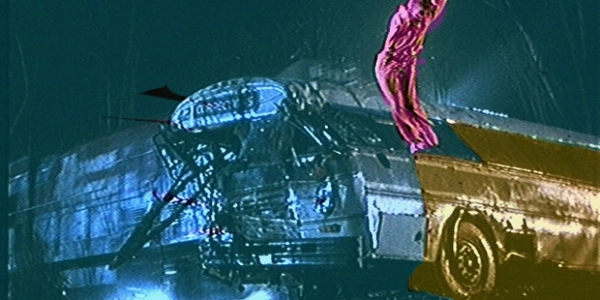

Above: Alexy’s wireframe setup for a Flubber puppy shot. Head to the vimeo page for a detailed description of the challenges of making this scene.

b&a: When you were animating, what kind of preview could you see of a finished shot at the time?

Philip Alexy: What I was able to see on my computer while animating was often just a bunch of spheres controlled by the spline rig I had developed. There were many late nights when I would be at ILM, waiting for the first frame just to render to see if somehow the mesh or rig or whatever worked properly. It was hard and taxing, but there were so many skilled and talented people working together, it never felt overwhelming or impossible.

Tom Bertino was an amazing VFX Supervisor and Roni McKinley was always a supportive producer. Scott Leberecht’s art designs for Flubber set the bar, Steve Braggs did his magic on the technical side and Julie Creighton, Amanda Montgomery and Luke O’Byrne kept things running in the production office. Everyone on the team was terrific: TDs and animators.

b&a: What did you take away from Flubber that you were able to apply on future shows?

Philip Alexy: What did I take away from Flubber? I was pretty young at the time and it was my first lead position, and to be honest, I made many mistakes. I wouldn’t be a supervisor again until several years later. I learned that leading a team was more that just having a title and telling people what to do. But I also had my first insight on how a VFX project works; from pre- to post-production.