We try to get to the bottom of the first comp done at Digital Domain in their tool.

Foundry’s compositing tool Nuke began its life at Digital Domain around 1993 and 1994. I’ve always wondered what film or project was the first to use Nuke to handle a composite. Was it True Lies? Maybe Interview with a Vampire? Or slightly later with Apollo 13?

In this episode of VFX Firsts, I run through the options with Hugo Guerra from Hugo’s Desk. We had talked to several Digital Domain crew members from back then about their memories of how Nuke got developed and where it had first been used. There are some great surprises that we relate from these conversations in the podcast.

In recent times, befores & afters has had a few different pieces of Nuke coverage, including this visual history of Nuke.

True Lies both started and released several months prior to Interview with the Vampire. Not to take anything away from Jimbo 😉

I did effects and some compositing on ten shots in True Lies. I was part of the missile team for the causeway Harrier attack, and those shots were mostly Nuke composited. The sequence was largely match-moved by myself, and then a combination of Karen Goulekas and I animating the Maverick missiles (which I modeled in Softimage, wrote the shaders for in Renderman, and that we animated in Prisms), with particle smoke trails we made in Prisms and shaded as smoke in Renderman thanks to Peter Farson. And for the missile launch I used Elastic Reality to help bridge from the real missile in the plate photography to the CG missile. That might have been one of the few shots in the sequence with final compositing in Flame/Inferno but I generated all the precomps with the transitions in Nuke.

When Aziz flies on the end of a missile through the office building into the helicopter, erupting in a fireball, that was largely Nuke, with some keys on the glass for reflection masking from Matador. And then there are various other shots that are more pure compositing that I completed in other parts of the Miami sequence with the Harrier either on location or on the translight stage (paper debris plates shot on stage, dust elements shot on stage, keyed in Nuke and composited in Nuke), often under the guidance of Price Pethel. I even tracked a bit of matte painting to fill in visible floor space in the shot where the Harrier pulls its tail out of the office building, in Nuke.

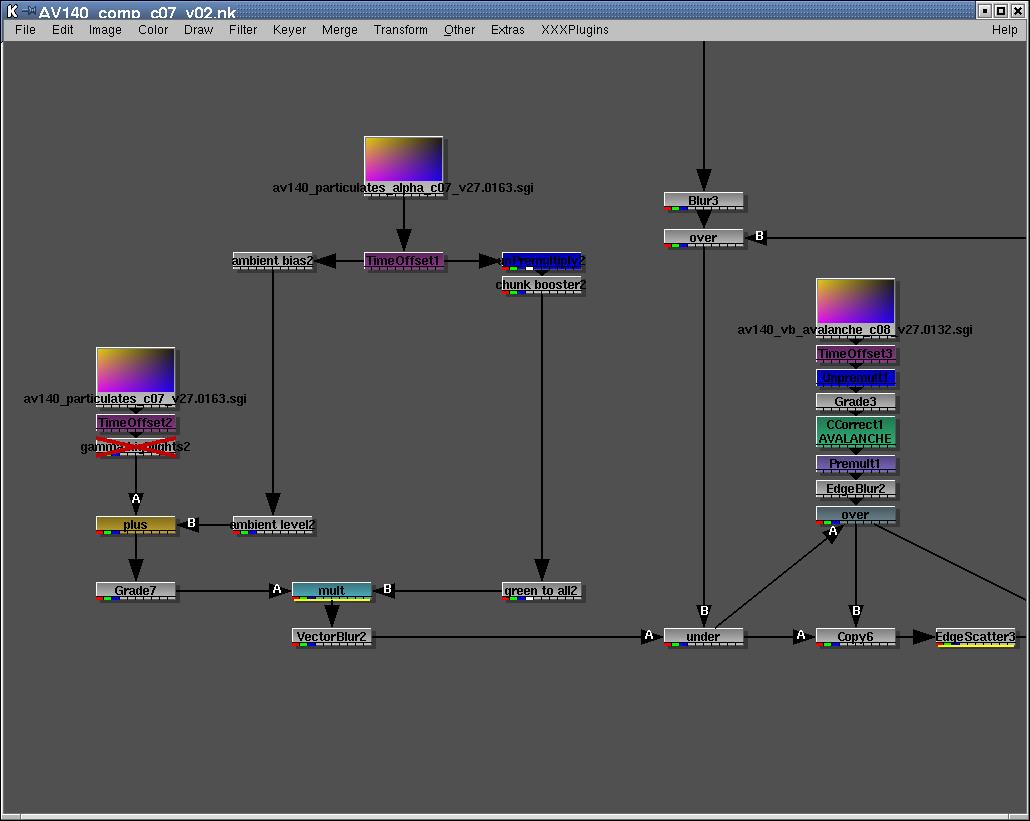

That last bit is kinda cool because you have to consider that Nuke had no UI at this point. Just a viewport you could view a layer with and a simple, BASIC-like script language to composite. That really wasn’t that unusual back then. Anyway, how did I track a matte painting in no-UI Nuke with no tracker node? You could pipe ASCII channel data into any parameter in even v1.0 Nuke and the viewport had an XY readout for the tip of the cursor.

I would advance the frame and visually track a feature, making note of the coordinate in an ASCII file, and then those coordinates moved the painting layer. I’d flipbook the result, see where there was wobble and make minor adjustments to the ASCII data on the bumpy frames until it was smooth and acceptable. I used the same technique for some signage replacement in Strange Days. We shifted from no-GUI Nuke to Nuke 2 during this project and Apollo 13. Nuke2 changed everything.

I don’t know that these are the very first composites created with pre-GUI Nuke, because in the months leading up to True Lies there were also commercial projects happening and I wouldn’t be surprised if someone tested an even earlier version in some capacity on a commercial. Outside the actual Compositing department, which was Flame/Inferno based, we used some combination of Wavefront VideoComposer (which I’m convinced is where AfterEffects got its layer paradigm) and sometimes Matador. The first ever official, paid project at DD was mostly composited in Wavefront VideoComposer, of all things, by myself and Mark Lassoff for a project nobody will ever see, sadly, a Tim Burton production company logo that ended up DOA.

PS> the football commercial that Phil talked about was very likely one of the Fincher directed Nike “Ref” spots starring Dennis Hopper. Fred Raimondi brought Fincher to DD and spearheaded that work.

Thank you, Sean!

Sean has an *excellent* memory on all this.

Thanks Alan. I wish my memory worked this well for everything, but I’m happy the DD days have been mostly etched in stone all these years.

Reading the comments was more interesting than listening to the podcast. Instead of inviting people that were actually involved in development and using the early versions of Nuke in production, I had to listen to this “Nuke spokesman” that has nothing to do with it, except for sharing his boring stories and second-guesses about what actually happened back in the day.

I believe Dante’s Peak was the first show to use Flame to Nuke, because Price Pethel remarked afterwards that ‘flame 2 Nuke worked just as we had hoped it would’.

I’m grateful that I had the opportunity to contribute to the design of the roto tool as well as a few other key features.

Larry Hess was the programmer responsible for the first besier/spline tool with non-uniform blurs, and for initially converting the pan and tile tool into a full 3d integration.

Around the time of Titanic there was a point where nuke was in jeopardy – Shake was being pushed as a viable alternative, mainly because their blur method was screaming fast, and nuke2’s was painfully slow.

It didn’t seem like a good plan to replace DD’s very capable internal software with something from an outside vendor, and if it was only down to the blurs, a solution could be found.

So I came up with a dynamic scaling technique over lunch after that meeting, and within a couple of days, had Bill Spitzak hard code it, and it is still the basis of the blurs and erodes in the latest Nuke. The number in every blur represents the pixel width at which the dynamic scaling starts.

After that was introduced, thoughts of shake dissipated, and much more effort was devoted to creating nuke 3.0 with multi-thredding and numerous other artist suggested improvements.

After that, Jonathan Egstad really leaned in to programming it, and deserves much of the credit for making the 3d system what it eventually became.