An in-depth Q&A with visual effects supervisor Andrew Whitehurst.

Note: this article contains plot spoilers.

Alex Garland’s Devs, which premiered in March on FX on Hulu, follows the plight of Lily (Sonoya Mizuno), a software engineer for Amaya, a quantum computing outfit situated near San Francisco. Amaya is run by Forest (Nick Offerman) and it’s also where Lily’s boyfriend Sergei (Karl Glusman) is employed, until he is given a chance to work at the company’s top-secret ‘Devs’ division.

After that, a wave of mysterious events unravel, including the true capabilities of Devs in producing a technology that can allow people to view projections of the past and future.

Now a regular collaborator with Garland, visual effects supervisor Andrew Whitehurst (Ex Machina, Annihilation) came on board Devs to oversee the VFX effort. This included imagery for inside and outside the Devs facility, the projections, the apparent self-immolation of Sergei, a series of car crashes, and a number of ‘multi-verse’ moments throughout the show.

In this befores & afters interview, Whitehurst outlines the principal visual effects shots in Devs, which were led by DNEG, and also included contributions from Nviz, Outpost VFX and an in-house unit overseen by Hadrien Malinjod.

b&a: Like some of your other projects with Alex Garland, Devs didn’t ‘feel’ like a visual effects show. Was that one of the things going in that was important for him and you?

Andrew Whitehurst: Yes, absolutely. The key thing with Alex’s projects is that the story comes first, and all of the imagery falls out of that. Whatever the imagery that everyone feels is right for that story is what we go with. Sometimes that means that there’s a big visual effects number. Sometimes it means there’s no visual effects at all. Sometimes it’s just a bit of helping out with some practical work. Alex has the idea, writes the script, and then we all talk and try to come up with the best way collectively of telling that story.

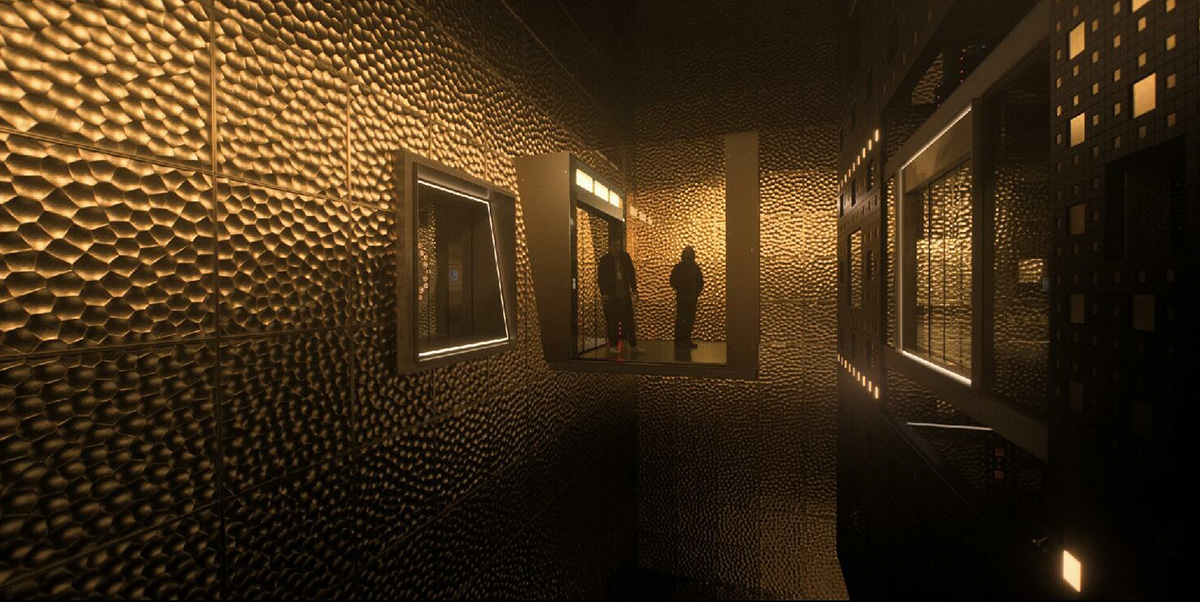

b&a: Tell me about the golden interior of the Devs cube. What visual effects challenges were there inside there?

Andrew Whitehurst: The approach that we took was that we obviously wanted as much practically there for the DP Rob Hardy to light and shoot and for the actors to be in, and for Alex and Rob to be able to stage the action in a believable fashion. So there was never any talk about, well, we’re just going to stick up some bluescreens and worry about it later.

Once you’re in the vacuum seal area – the office floor level of the cube – that is practical. That was built on a sound stage in Manchester, including the gap for the gold walls. The glass capsule that floats across is real. Obviously it didn’t float; it was on a massive steel dolly that grips could push across the gap.

What that then meant was that everything that was above that – the top and bottom of the cube and the inside of the box – had to be visual effects. And because of the way that the light is always swirling around, trying to tie all of that together meant that we often replaced all of the gold panelling. But we tried to keep as much as we could.

Then any shots where you are either very high looking at the cube or very low looking at the cube had to be full-CG because you’d be through the ceiling or through the floor of the sound stage to try and get those angles to shoot anything for real.

So we were very much in the business of major set extensions, sometimes replacing a lot and sometimes very little. Then there was the painting out of the dolly that the capsule was on. There was a lot of reflection clean-up in the glass; [set decorator] Michelle (Meesh) Day and [production designer] Mark (Marco) Digby like to torture us on every project I’ve done with them and Alex [laughs]. They put big glass boxes everywhere which meant lots of cleaning out the reflections of cameras and lights.

b&a: Were exteriors of the Devs building a fully CG creation?

Andrew Whitehurst: Almost. The meadow that the ‘bunker’ is in is a real place at the University of California, Santa Cruz. On set, Marco and Meesh had worked out how big the exterior structure needed to be. They marked out the area on the ground with posts. Along the facade we also ran bluescreen up to about three feet high. We knew that we were going to have grasses that would be against the front of the cube, so we just had a whole section of bluescreen which meant we could key that to put the grass back over the CG building. They also built a tunnel entranceway. The actual door section where people walk in and out of the cube was practical.

What changed was, during postproduction, Alex decided he wanted something a bit different from the original idea. The original building was going to be made of large metal panels that gently moved and had patterns playing across them. Alex felt that what we actually needed was something more brutalist and concrete like the rest of the Amaya corporation buildings. So we redesigned the building to be the thing that you see now.

That actually was a little bit more complicated than we imagined because it had these buttresses that stuck out. So there were now areas where we had a CG building where we didn’t have bluescreen covering it because our original structure was not as big. So we ended up having to do some roto and some additional work to get that building to fit into the plates that we shot, thinking that the structure was going to be something slightly different.

b&a: Back inside Devs, I thought the imagery for the projections was beautiful – how was that conceived?

Andrew Whitehurst: Well, there were two things that we felt we needed to try and nail the design of in pre-production. One of which was how the multi-verse was going to be realized, and the other one was the visualizations. The main reason for wanting to figure out what the visualizations should be like ahead of time was that the plan was to do as much of that work upfront and then structure the shoot so that we could film the plates that we needed for the visualizations earlier on in the schedule, give DNEG enough time to process them and do the work to actually make the visualizations, and then project them live on set for the visualization scenes in the Cube.

We had a 4K laser projector on set so when the actor is actually standing in front of the visualizations, they are actually looking at, and reacting to, these images being projected live, and being lit by them.

We had a lot of initial conversations about what these visualizations might look like. We were trying to suggest that you have a computer simulation of everything, so what you want is some sort of visualization of that that’s trying to describe this space. But also we needed to tell the story that over time the simulations get better as the technology is improved.

Often the way I work with Alex is, I’ll just go do some concept tests because I have a reasonable idea of how he thinks and I can quickly go and mock up some crude things. Then I can hand it to actual effects artists to do it properly.

I did a whole bunch of tests mucking about in Houdini right at the beginning of the project. I bought myself a Kinect on eBay, and with a bit of Python and some other gubbins, I got it to port into Houdini. The Kinect was fun because it gives you depth information. I was trying to think about ways of interestingly visualizing these volumes.

“Generally speaking, if you give Alex the option of a normal one and a weird one, he will usually go for the weird one.”

I was doing voxel kind of experiments, filming me waving my arms around in steadily refining blocks. It sort of worked but it felt a bit inelegant. It ended up looking like Minecraft, to be honest, so it wasn’t that appealing, but it had an interesting quality to it, even though it felt a bit too clinical and clear.

Then I was looking at how, when you’re doing interactive renders on a modern ray tracer, they do multiple passes across the whole image. So it starts off looking really sandy and gritty and horrible and then it refines and refines and refines as it shoots more and more rays.

That was a look I thought could be interesting because one of the key narrative points the visualization had to achieve was it had to get better over the course of the series as the technology improved.

I thought, well, we could do something where at the beginning it’s this sort of sandy, Lidar-feeling version of reality. There was a practical problem with that, however. We’d talked about filming things either with a Kinect or with a higher-end Ncam-like version of the same thing. That started to get a bit complicated and risky if it didn’t quite give us the data that we exactly needed.

Instead, we thought, let’s try and come up with something whereby we can just shoot regular footage and then process it afterwards. We then thought, we live in a world where there’s lots of stereo conversion that happens for movies and they’re all shot flat and the way that it’s done is you rotoscope the various elements and stick them on cards in depth and that’s how you get a stereo image. So, why don’t we do the same thing? Except, rather than making a stereo image, we’re actually putting that into Houdini in depth to then move some points around.

We designed a system of points that produced clouds of little particles that are drifting or being pushed around by currents in water. It felt like the whole thing was alive. Then we modified the system so the points would try and attach themselves to their correct origin point in space. This countered the other force that was saying, no, you should be free, you should be chaotic. And then we could literally dial it up and down as much as we needed it to in order to keep the shot from being too discrete and too clear.

View this post on Instagram

So, for seeing Christ on the cross, for example, there needed to be a slight element of intangibility to that. Then right up to where they introduce color and it gets more and more refined, until by the end you’re actually looking at photography.

Our process worked well because it ticked all of the narrative boxes of keeping things mysterious when they needed to be, being able to refine in a fairly easily and understandable way over the course of the series, and it had an inherent aesthetic that was beautiful to look at.

When we actually got to see it as a 4K projection on a screen that’s eight feet high and 16 feet wide, it looked amazing. Rob could use it as a light source and for framing his shots, too. Once we figured all that out, we really went with it.

b&a: When you had to go between real life and those projections, there were some particular transitions. Was there anything done in visual effects rather than editorial for those?

Andrew Whitehurst: Alex and [editor] Jake Roberts are very good when it comes to elements of the series that have a big visual effects component. They will say, look, we’ve cut this and this is what we think seems to work, here are the pieces, go and make it work as a shot, bring it back, and if it’s way shorter or way longer, that’s fine, we’ll fit it in.

So for all of those transitions that go from real-life to the visualizations, we took the plates for the beginning and the end, and then it was a question of DNEG FX supervisor George Kyparissous running a sim and us looking at it and refining those sims until the timing felt right and it flowed well. Then we’d hand that over to DNEG compositing supervisor Giacomo Mineo’s comp team to blend it altogether.

b&a: How was that giant haunting Amaya girl statue crafted?

Andrew Whitehurst: It was pretty clear that we couldn’t do anything practically for that. The shots where you see her feet contact the ground is an amphitheater at University of California, Santa Cruz. There was no way of bringing anything big down there, even if we had been able to fabricate it.

For the various aerial shots where you see the statue above the trees, we knew that we were going to have to shoot in several different places to get the kind of tree lines that we wanted. So again, the actual asset had to be CG.

The way it was done was, we photogrammetry’d the little girl. Alex would talk to her and direct her and then we’d take a shot. We took about 15 shots. We had a look at the images from the shoot and Alex picked the one that he thought was the most appealing pose. He wanted a couple of changes made. In the actual photogrammetry, she’s got one hand held up as you see in the finished sculpt, but the other hand was tucked underneath the strap of her dress. Alex wanted it to be that both of her hands were held up.

We took the photogrammetry and then there was some re-sculpting. Daffy Hristova did that. The skin, the dress – all of that is super-close to the photogrammetry apart from the one hand that had to be fixed, and the eyes that were sculpted as you would in marble, with carved irises and pupils. And then Daffy had to sculpt all of the hair from scratch because Amaya has very fluffy hair, which obviously doesn’t scan very well or reconstruct very well. So Daffy sculpted all of that from scratch in ZBrush as if it was a piece of traditional sculpture or statuary.

Then it was the question of, what should the surface finish be? Should it be concrete or a fibreglass material? What if it was this giant brutalist four year old towering over the forest? We tried that and we also tried a more orangey yellow paint job, matching the color of the rest of the Amaya Corp signage. But in the end the hyperreal weirdness of this gigantic, pop-art, Jeff Koons-type sculpture was enough. Even though it’s the most ‘photographic’, it felt the weirdest. And generally speaking, if you give Alex the option of a normal one and a weird one, he will usually go for the weird one. This was most interesting and most unsettling.

b&a: How did you approach that CCTV moment where we ‘see’ Sergei setting himself on fire, but then also later where the ‘glitch’ is revealed?

Andrew Whitehurst: In the original screenplay it was described as a glitch in the video. I wondered, well, what is that exactly? It could have been a compression artifact. There’s a lot of things that wouldn’t necessarily say, ‘trickery has happened here’.

So I said, why don’t we literally clone a section of fire so that you’ve got two bits of flame that do identical things. I was pretty confident that, on the run, until people have it pointed out to them, they wouldn’t notice. And, actually, a bit of dodgy cloning is the sort of thing that marks out a rushed visual effects job. So it had that element of authenticity to it, as well.

I must say, we are scrupulously honest about this. When you see the first bit of CCTV footage of Sergei setting himself on fire, the trickery is in that as well, if anybody wants to go back and look.

b&a: Is it a cloned Houdini fire sim, or a cloned practical fire element?

Andrew Whitehurst: A bit of both. The majority of it is an effects Houdini sim. There are a couple of little bits just for some shapes here and there where we used an element.

b&a: There’s a moment when Lily steps out of the office to go outside – how was that done?

Andrew Whitehurst: The way that was filmed was we were up high on location, but we had to build a huge platform out from the front of the building, first to put cameras on, but also obviously for safety reasons. We had to digitally re-create the whole front of that building for all of those shots where you see Lily and Kenton standing up on the ledge. Nviz did that work. They did some really beautiful invisible work there, supervised by Richard Clarke.

b&a: How much traffic visual effects was involved for freeway scenes and the car crashes in the show?

Andrew Whitehurst: The most complex one was the freeway crash. We did a little bit of second unit shooting on the actual section of freeway in San Francisco, but there was never any possibility of doing any stunt work there just because it’s an open road. We had an array vehicle so that we could shoot plates to do rear screen projection or blue or green screen car interior shots, which we then did back in the UK.

For the actual moments around the crash itself and immediately afterward, we utilized a location in Oxfordshire where they have a long section of private freeway to help emergency services practice doing what they need to do, so they don’t mind you smashing things up!

We were able to build a central concrete section of the road with a gap and then we were able to film stunt cars driving along and then swerving left and then have the stunt car drive through the gap. We then did our digital takeover and added CG to fill the gap and did the crash digitally. Then we had to create a full two-and-a-half-D cyclorama of San Francisco to go all the way around that for the driving and then for the moments afterwards when Lily gets out of the car and runs away and Kenton surveys the scene.

b&a: How were the multi-verse moments realized?

Andrew Whitehurst: For all of those multi-verse shots where you’ve got lots of versions of people walking around, all of those are shot motion control. The most complicated one of those was the dam shot in episode seven. And the reason for that being complex was because on the real dam in Marin County we shot something not anywhere near as elaborate as what’s there now. We put that together while the rest of the shoot was still happening. When we got back to London over Christmas, Alex wasn’t sure it worked and thought we might need to do something else. So we designed the shot that you now see in episode seven which has the big sweeping camera move right around the dam.

The art department built a tiny set-piece, literally just a handrail on a little bit of the top lip of the concrete about six or seven feet up on a rostrum in the car park in Manchester where we were shooting the cube on a January morning. We shot again with mo-co plus some other angles with the actors and a stunt performer doing all of the drops.

And then I was extremely thankful that when we had been in California, we had Lidar’d and photographed the dam very carefully because we had to create an entirely CG environment for the whole dam and everything that was surrounding it. That shot, apart from the people in it, is completely digital. The other multi-verse shots were a little simpler but still had mo-co photography, often with a grip with a greenscreen walking behind the actor so that we could roto or key them out and comp them back in.

b&a: Finally, I really loved the aerial helicopter moves above San Francisco, they also seemed particularly haunting as well. Was there any visual effects work you had to do there?

Andrew Whitehurst: All of those are totally straight photography. The only things that we had to do in terms of any clean-up was where there were a couple of shots where the AC power cycle of some of the city lights was slightly out of sync with the camera. We had some buildings where you get a sense of the lighting flickering a little, and we fixed that. But apart from that those shots are exactly what San Francisco looks like.