How do you make a CG character eat, anyway? Weta Digital reveals all.

Did you ever wonder how they animate a CG character eating? I mean, is it different from animating that character talking? What extra things have to be rigged and modeled? What do you actually ‘do’ with the pieces of food?

These are questions I asked myself after watching Alita: Battle Angel. In that film, Alita (a performance captured Rosa Salazar brought to life by Weta Digital) eats…a lot. She has an orange. She has chocolate. And a pretty scrumptious looking hot dinner, too. Those shots just seemed to feature something extra that Weta Digital had done to make them stand out. But what?

Then I remembered the studio had pulled off something equally as successful for Bad Ape in War for the Planet of the Apes, when that character talks to his new friends with a mouth full of cracker. Again, this was based on the on-set capture of a real actor, Steve Zahn, with Weta Digital doing something magical with the eat-with-a-mouthful-of-food performance.

Eager to find out exactly how they pulled off those eating scenes, I asked Alita: Battle Angel animation supervisor Mike Cozens and War for the Planet of the Apes animation supervisor Dan Barrett how Weta Digital had managed the munching process.

Oranges, chocolate and not ‘breaking’ the captured performance

b&a: Had you had to animate a character eating before?

Mike Cozens (animation supervisor, Alita: Battle Angel): I haven’t really done that before. It was a new challenge, and a new challenge with a character like this, that had such a level of fidelity and detail in the performance. For that first orange scene, not only was it the eating, it’s a dramatic scene where Alita’s dealing with a bunch of things. She’s struggling to remember who she is and Christoph Waltz’s character is consoling her. There are multiple scenes in the film where she’s eating. She eats a lot during this film, you know…

b&a: So, how was that orange scene filmed?

Mike Cozens: They shot Rosa and Christoph Waltz, who performed together. A big part of process is having the actors that are playing the digital characters performing in sets with the other actors. You get genuine performances, and her reaction to what’s happening in the scene are her reactions to Christoph and the things around her. Our challenge once that’s done is to translate that onto the Alita character.

b&a: Now, Rosa had a full body capture suit on and a facial capture camera, but when she’s eating something, I’m guessing you don’t always have her wearing the face camera, because I assume that gets in the way?

Mike Cozens: Yeah, there’s a bunch of scenes in this film where, either due to proximity, or for other reasons, she wouldn’t be wearing a face camera. Same thing with her kissing – there is no other reference other than the shot camera and the witness camera. What we usually had was all the mocap cameras in the space, and then there’s witness cameras that are all time-sync’ed, and they’re running to capture different angles of the performance. And then there’s the hero camera. Now, when we don’t have a face camera – which means we don’t have marker data – we’re keyframing the performance using the witness camera and the main camera.

b&a: When it came to blocking the scene where she puts the orange in her mouth or when she’s eating other things, tell me about what some of the obvious challenges were with those shots.

Mike Cozens: The critical bit of motion on a face is what your jaw is doing. It’s the one bone you have in your face that is moving around. And so, the jaw motion, the jaw path, as we call it, is your foundational bit of work. When her mouth is open and you can see the teeth, you can set the jaw correctly. And when it’s closed, you’re using indicators on the surface of the skin to position the jaw correctly.

Our face puppet is set up in a way that we fire individual muscles, and then we layer different muscles on top of one another, and then we’ll tweak shapes on top. You build it up from the broader more informative muscles that are firing on the face, and then layer in the detail. So, it’s about going from broad strokes to smaller details, starting with the jaw. Another critical thing is eyeline and eyes. [Filmmaker] Jim Cameron always talks about how performance is really about what’s happening on the face, and in particular, what’s happening in the eyes.

From there, you can contain blocking on the lower face – what’s happening with the mouth and whether it’s dialogue or something like eating. There is overlap in both of those things, but they come together as you fine-tune the animation. And then on top of that, if you’re keyframing something, there’s all the behavior of the neck which is sometimes driven from muscle shapes in the face.

b&a: When Alita does take a bite out of that orange, the orange deforms and of course ends up as little pieces in her mouth. Tell me about the role of animation in just making the very logistical parts of that work.

Mike Cozens: In that scene, Dr. Ido (Christoph Waltz) passes her an orange, and the camera team will do a matchmove for Christoph’s hand so we understand where that hand is sitting and where that orange is sitting in 3D space. Fortunately, the orange is a fairly simple object but the model team will sculpt that, just so it matches perfectly, so we can go from live action to a digital hand-off. Because we understand where the hand and the orange are sitting in space, we can fine tune our body motion of Alita for her picking up that orange. And once she picks it up, it becomes a CG version of that orange. Animation will block out all that including the grab and the bite.

Then, the tongue was a big thing that played into that performance because you’re looking in her wide open mouth, and she’s chewing on the thing. There’s a point where you actually see – when she first takes a bite and she takes a bite of the skin – that you can see the food on her tongue for a beat. And I think the comp guys lifted the actual element off the plate and placed it back in Alita’s mouth.

Things like deformation on the orange, and even on her face in different moments will be handled as a shot sculpt from the model team after everything’s passed through animation and baked out. They’ll do a render, they’ll make some notes, or we’ll make some notes, and we’ll refine some extra details with shot sculpting, which is pushing points around in a dynamic modelling way.

b&a: I tend to ask a lot about mouth and face shapes when I do interviews about these films in terms of speaking and phonemes. But are the mouth and face shapes different when someone is eating, versus when they’re talking?

Mike Cozens: That question goes to how we built the face puppet. The thing is, her performance carries the film and there’s so much dialogue, and dialogue is often happening in a very subtle range. Even when we’re intensely communicating with someone, a lot of the shapes that are happening on your mouth are in a very subtle detail-y range.

So we had to first increase our understanding of what was happening to the mouth in dialogue and to create phonemes that captured this subtle range. In order to do that, we really took a look at what’s happening underneath the skin, how the jaw, the gums and the teeth play with the back of the inside of the mouth. All of that created a lot of work in terms of getting the inner structure of the mouth working correctly, which sounds maybe strange when you’re really looking only at the outer surface. But something that we spent a lot of time in getting correct with the models team was the inner structure of the inside of the mouth; the inner wall of the mouth. And there’s a lot of structure that, again, when it’s pressed up against teeth and gums, really shapes the way the outer surface looks.

Now, you could do almost animate eating by just deforming the model. If your mouth is doing something really extreme, like really mashing or chewing on something, your mouth is distorting and deforming in all sorts of crazy ways that you don’t typically do.

And you could just move the mouth and the skin around and mimic what that looks like, but as humans we have an innate understanding of what is cheated and what isn’t on a digital face. So building all the structure and the behavior in the face and around the mouth allowed us to get really close in animation by using actual muscles to hit these shapes. It gave a very accurate representation of the performance from Rosa. There’s a little bit of shot sculpt work to just get it just over the finish line, but a lot of the work that was done in creating this particular face puppet, and creating it from the inside out – bones, bone structure, muscle, shapes, the attachment points, the fat pads – really helped us maintain the correct volumes and the correct behavior on the face.

The amazing thing was to have Rosa there, of course. She’s got her lines, and she’s got her marks, and she’s delivering them consciously. But then there’s a certain amount of observable unconscious movement that is just happening just because you’ve got that actor in there, and they’re doing their thing.

I couldn’t ask an animator to come up with all this from scratch, in a cohesive way, that would drive the performance through the film. I mean, that’s the magic that actors bring, and in shots like the orange scene, the actor brings the performance, and then our job is to not break it.

Bad Ape eats a cracker, and it’s mesmerizing

b&a: For me, that cracker scene with Bad Ape is such a memorable scene, as much as Koba’s ‘playing dumb’ sequence from the second film where he ends up killing the guys.

Dan Barrett (animation supervisor, War for the Planet of the Apes): That cracker scene was such a lovely moment wasn’t it, just because he’s basically breaking bread with friends. I loved the scene so much because it was this opportunity for him – meeting new friends – it was just so magical.

b&a: How was it shot?

Dan Barrett: Obviously, we had a fantastic performance from Steve Zahn, and on the day, he had his crackers and that was pretty much it – what you see is pretty much as he delivered it. Because it was tied into dialogue as well, there was no room for deviating from his timings, so we had his performance there at the heart of it. And we used that as our guide for the eating.

b&a: And then, obviously an ape is different physiologically to a human, how did you look to transfer Steve’s eating to Bad Ape?

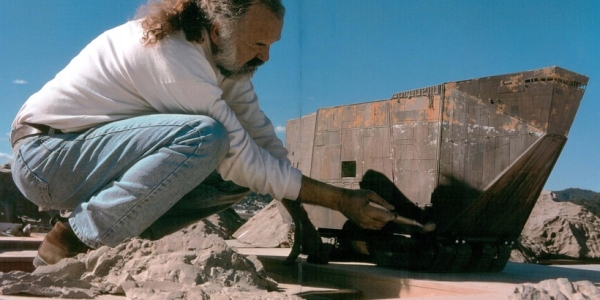

Dan Barrett: Luckily, they’ve got some chimpanzees at Wellington Zoo here. We’ve spent a bit of time pointing cameras at those guys over the years, and we had some fantastic footage of a chimpanzee called Marty. I think he was the alpha at that time and we had great footage of him eating. One of the magic things that chimpanzees do is that they are very ambidextrous with their lips. They have these amazing prehensile lips. We’ve got this great bit of footage where he’s chewing on something and you can see him for a moment wonder what it is that he’s got in his mouth. He holds a bit of food in his lower lip and sticks his lower lip out far enough that he can look down and see it, and he just carries on eating satisfied with whatever it is he had in there.

We had a lot of that in some of our early tests, where we were building a couple of facial rigs to stress-test them based on the malleability of a chimpanzee muzzle. In fact, the animator who animated on the shot, Eteuati (Jack) Tema, had done a bunch of testing with some of the early rigs, some of this reference of Marty. So we were pretty familiar with it.

When you look at the shot side-by-side of Steve and the final animation, they’re very much the same except that the lips just do a lot more in Bad Ape’s render. There’s a couple of moments Jack found to really protrude that lower lip, just to keep him as ‘chimpanzee’ as possible.

b&a: What approach did you take with the actual cracker?

Dan Barrett: It was rather simple in this case. He’d taken a single bite, and so in terms of what we had to consider with the food with regards Bad Ape, there wasn’t too much. He was holding most of the food within his mouth in the main shot. We had an object in there that was sort of floating around. We actually did a crumbs pass on the food a bit later. Steve was eating a cracker, so we did have reference of where the cracker was in Steve’s mouth at the same time, which was helpful.

b&a: What do you recall was one of the more challenging aspects of how the final eating animation was done?

Dan Barrett: We had a lot of the handles around the lips, which we could essentially sculpt on the fly. And then we didn’t really have anything for pouty cheeks, we just had ‘cheek puff’ attributes on the face puppet, which were designed for a character holding air in their cheeks, which was helpful for us. I think we did a little bit of shot sculpting at the end, just to get a more generalized look of the bulge in the cheeks, and for some finessing at the end.

b&a: Does that CG piece of food itself present its own challenges in animation? We often talk about the character that’s being animated, but what about the piece of food itself?

Dan Barrett: Obviously it does add another layer, it’s an animation element that’s interacting with something else, in this case, the interior of the mouth. More than one bite becomes even more of a challenge. The single bite is often a little easier to deal with. But in the case of the shot here, what we saw in Steve, he wasn’t exercising much decorum, in a way. I mean, he was Bad Ape, he wasn’t trying to hide it.

b&a: The comparison between Steve Zahn and the final shots is so interesting – it just shows how much these chimpanzees can do with their mouths.

Dan Barrett: Yes, when you look at Steve eating, it’s almost a little more incidental, in a way. I mean, he’s clearly eating, but because of the work that Jack did and looking at the chimpanzee reference, there were certainly some fantastic moments in the final shots. There’s a couple of moments where Bad Ape turns his head down. It was a great opportunity to really extend the lip and you can see him carrying that cracker, rolling that cracker around, in between the lines he’s delivering.

I think it’s a fantastic challenge. A shot like this for an animator is a great opportunity because when it comes to dialogue and eating, there’s a lot you can do with a face like Bad Ape’s.

Alita: Battle Angel images © 2018 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All rights reserved.

War for the Planet of the Apes images © 2017 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All rights reserved.

Great job, but I ask you questions, why didn’t he say what software is used to capture face movement? I would like to know what software to try to learn how to do. I hope that you answer me and I will thank.

Hi, thanks for your comment – Weta Digital typically use a lot of proprietary (in-house) software for their facial capture, combined with some other off-the-shelf tools.