Breaking down that confronting horse death by cannonball, the Battle of Waterloo, a fight on ice, crafting ships at sea, and invisible effects you might have missed.

In this in-depth conversation with visual effects supervisor Charley Henley about Ridley Scott’s Napoleon, befores & afters looks at several key VFX moments in the film.

Henley, the production visual effects supervisor, who also hails from MPC, breaks down the biggest VFX scenes.

These include the intense horse and cannonball shot in the first battle, the massive Battle of Waterloo, the ice battle of Austerlitz, how the film’s ships were made and some of the invisible effects shots in the film you may not have noticed (such as 1200 candle shots).

Read on for Henley’s descriptions of the role of visual effects in collaborating with many of the different departments on Napoleon, such as with Neil Corbould’s special effects team and production designer Arthur Max’s art department.

*That* horse shot

The film’s first battle is the Siege of Toulon, in which Napoleon leads his troops to a victory by storming the city and repelling British ships with artillery. However, early in the fight a cannonball rockets directly into his horse, killing the animal and causing Napoleon to violently dismount and continue covered in blood.

Charley Henley: To start with, we had a lot of discussions with special effects supervisor Neil Corbould about, ‘How are we going to share responsibility for it?’ He’s done quite a few horse rigs before, and he had a good setup that was mobile enough to go on location in Malta. So we felt we could get a real performance out of it and have something Ridley could shoot.

It started with Neil’s guys gathering a lot of reference of horses falling. They built an animatic to show Ridley what the actual shot would be. They then built a motion rig that could do a kicking motion, reflect the impact of the cannonball, and throw the rider off. They also had an exploding chest piece for the impact. They built a horse head, while we scanned the horse we were going to use and then would match that in CG, as well as to the dummy horse.

On the day, we ended up putting this moment on the side. At one point, we were trying to get right in the action, but the way the action works, Ridley plays out huge beats of the actual battle, and then we’ve got multiple cameras shooting that, and then to put this rig in the middle of it all didn’t really work. It was just not going to work with the flow.

We did quite a few takes on it, which was quite rare for Ridley, but we did a few takes and we shot certain angles. With that, we had some great grounding–like everything in the film, we tried to get something real and build off it. MPC did that particular shot, in post, while BlueBolt did the work in that siege scene. We mixed it up in terms of taking over with CG, and how much of the real actor was falling.

Quite a lot of time was spent on the horse legs, because there were no legs on the rig. We found some unfortunate footage of a horse that really was collapsing. It was the way the horse reared up, and the back legs collapsed under its own weight, and so we copied that as an action for how the legs changed. In the end, it was a mix between CG and the dummy to get the shots working. We put a cannonball in, obviously, and we had a mix of practical gore effects and CG gore effects for the final shot.

Staging the major battle

To depict the Battle of Waterloo, Scott filmed in the UK countryside with 14 cameras and an array of extras, horses and practical effects. Aided with elaborate scans of the location and soldiers and horses and weapons, plus motion capture, MPC (visual effects supervisor Luc-ewen Martin-fenouillet) then embarked on bringing many different elements together for the final confronting scenes.

Charley Henley: We had a great studio space with a war room to plan this out, where everyone would gather. Ridley would do drawings on big A0 pieces of paper, and plan out what we’re doing.

In terms of previs, we did do some visualization of the layout of the armies, but generally we didn’t do a lot of previs. Ridley was evolving a lot with his own boards and with a lot of drawings in meetings where he’d draw out on paper how it would work with arrows going everywhere, which was so interactive and live, that the previs was almost just a bit too slow for that. We were going to shoot it like it’s a real battle, as if it’s really happening, so the idea was to cover it in an unpremeditated way. We wanted to be more flexible and live, depending on what we’d find on the day rather than, let’s match this shot, let’s match that shot.

When we were looking at the different terrains that we were to shoot, Arthur Max’s art department built little set pieces of the battlefield, and we had little soldiers there. Then, a big key part of it was Ridley’s storyboards. He draws his own storyboards and now he’s doing them in color and they’re really beautiful. One thing was, he drew out particular weather at the beginning, and so we knew that was a big part of it, that it really had to rain.

There was a lot of working out the layout of the area, but we found a place that had very good sloping hills on two sides, which was apparently how it was with the Duke of Wellington’s side being a little bit higher. There was a tree that had to be there, too, which we originally thought would have to be in CG, since it’s so iconic in terms of Wellington standing next to the tree. I was very happy that the tree that they managed to put in there was real.

Shooting Waterloo (with VFX in mind)

14 cameras on the ground captured hundreds of stunt performers and extras, with Neil Corbould’s SFX team handling an array of practical battle effects, including air mortars that could go off right near actors.

Charley Henley: We came to a sweet spot of working out that we needed about 700 people for these scenes, which were mostly stunt guys, and then we had about 100 cavalry. In a given frame, that’s quite big, but if you go wider, that’s where we needed to fill out the frames.

Ridley stages things in an incredible way where he has the beats of the battle, one thing at a time. He will run scenes pretty long, but with multiple cameras covering it, which meant that we weren’t always shoving them all in front of camera, because it would just slow down the dynamic and become less free-flowing. So, it’s very organized but it’s also spontaneous and there’s an energy to everybody gearing up and then going for it. If you start doing too many takes, then you’re ruining the ground, people tire out, and it takes a lot of time to reset as well, obviously.

So, we shot all these cameras, and then on the sidelines, we had another team there. Hamish Doyne-Ditmas, the director of photography VFX unit, would be there trying to shoot in the same light while everybody’s costumed. And if the numbers of people in a shot weren’t all that we needed, we’d say, ‘On the side, seal that lot off.’ Then, Richard Bain, our on-set VFX supervisor would go and try and shoot elements for that. It might be filming some soldiers close up with particular actions.

Neil Corbould’s team set up amazing impacts from cannonballs (which we also shot on the side sometimes as elements for explosions). Actually, he set up something like an air mortar under the ground, so anyone could walk over it and just explode and they were unharmed. He showed a test to Ridley apparently, and Ridley was like, ‘Oh my God. What have you done to the guy?’ Then the guy got up and was totally fine. It was just air and dirt being thrown up.

Neil manufactured 14 real cannons that could all fire black powder for real, and a proper flash would come out the front. But given we could only do that when no one was in front, Neil figured out a system that would fire out talcum powder as a plume of smoke. We still needed to add muzzle flashes to most of the shots.

With the cannonballs, you don’t always see in films like these the actual cannonballs flying out. Ridley said, ‘I’ve seen a military firing large shells, and you can see the shell flying through the air. I want to see the cannonballs!’

We did some research, and it turns out cannonballs didn’t necessarily fly that fast. They came out fast, slowed down, and started dropping. On average, they’re going about 120 miles an hour. So, it’s correct that you would have been able to just about see them. So we had them flying out of cannons, in front of the cannons, and then we put them in just before the impacts coming in.

Scanning and mocap (and the challenge of multiple costumes)

For the Battle of Waterloo–and other battles in the films–the VFX team would rely on a wealth of captured data from the battle scene, including actor photogrammetry scans, aerial drone photogrammetry, horse scans and weapon scans to build matching CG assets. One particular challenge was the myriad different costumes worn by the performers. An additional motion capture shoot provided horse and actor movements.

Charley Henley: David Crossman is the costume design master of military costumes. The idea was always to make the costumes as authentic as possible. This meant they couldn’t necessarily buy anything from a stock shop; instead, they found real costumes to reference and then copy. I think they made something like 4000 costumes. But, the historical accuracy side of this is that, for the French troops, they didn’t actually supply them with trousers, they had to bring their own, and that meant that everyone’s trousers are different (in fact they’re more like pyjama bottoms). Then, with the cavalry, there’s so many different regiments, they all have different outfits.

All this meant we had so many different outfits to match to be able to put our CG performers side by side with the real ones. It was therefore a massive scanning job to get everybody acquired. Visualskies did all our scanning, and we were frantically scanning everybody and all the horses and the props. Since we shot these battles on location, it had to be done in our tent city with a mobile scanning unit. The team would be doing the sets with their drone scanning, and then we’d have another booth to do the cyberscanning.

After the physical shoot, we then did a lot of motion capture with The Imaginarium Studios. This was with stunt performers for battle scenes, and also for horse and riders. The horse and rider mocap was particularly challenging because the mocap area was limited to a large and indoor space, and matching the speed of the galloping from the day was very hard. Also, the fact they were going downhills, the complexity of them all interacting with each other, and all the unique actions, were hard to match. Luckily, we had a lot of great live action and it just helped us in anything we had to build and animate in CG because we knew what it had to match to.

A shout-out to the roto teams

Matching their CG creations to the live action scenes was a significant challenge for MPC, requiring initially a large rotoscoping and matchmoving effort.

Charley Henley: One of the things we decided to do was not rely too much on bluescreens, but to be a lot more agile and to just ride with the type of crazy machine that Ridley was demanding. We knew we were going to need a lot of roto. We knew there’d be clean-up. But we knew it would give us the best result and the roto teams from all the companies were fantastic.

One of the pieces of cleanup involved some of the many film cameras in the frame. I mean, they were amazing. That team has worked with Ridley for so long, so they’ve got a way of hiding themselves amongst the action even when it’s covered with multiple cameras. They’re masters of it. It’s like this crazy logistical chess game. They’re brilliant at it.

So, not that many cameras needed fixing but sometimes, on a wide, we’d see a camera pop up with the operator dressed in period costume. You would have got away with it in the old days, but nowadays, it’s hard to not get into the detail of these shots. You know, ‘We can’t have that coffee cup in the back of the shot,’ even though no one is ever going to know.

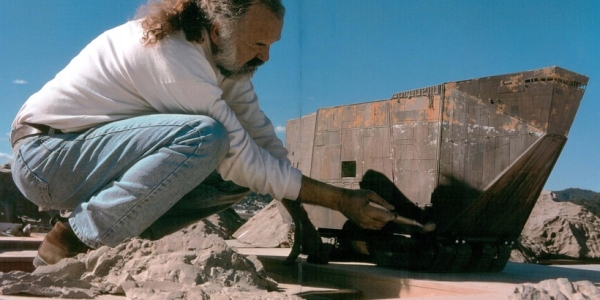

The art of period ships

In the Battle of Toulon, and in other scenes, several period tall ships are shown. Some are at anchor and others are full-sail. Many ship shots also involved battle damage and fiery moments.

Charley Henley: Most of the ship work was done by BlueBolt, supervised by Henry Badgett. We knew we were never going to get hundreds of real tall ships, there’s only a few of these around. We were very lucky to have a beautiful boat commissioned for us. The art department did an amazing paint job on it. We then adapted it for different scenes, so it actually played a couple of roles. We tried to put that ship in every shot that we needed to put ships in.

Off Malta, we had this camera boat, and we used that to get all the shots for the at-sea scenes, with a drone on board the boat and a crane arm off the side of it. They’d put sails up and down and we’d shoot all kinds of reference, then we’d take all that and try and simulate the shots that Ridley had drawn for the battle scenes.

Ultimately, for almost every shot, we had a real boat in it, which was a relatively small one. It was 34 gun, but something like the Victory is 120 gun. The Victory is actually in Portsmouth, and we were able to go and shoot there, so it’s the film, too. We shot interiors in the real Victory in Portsmouth, and we did an exterior shot where Napoleon rides up to it, which we shot for real there too. We scanned the ship and then we used that to help build more of the armada.

Bluebolt created these beautiful ships, and I just wish there might be a side movie where we could showcase them more! They’re so good. They have dynamic ropes and sail simulations and everything.

We did actually also considering doing miniatures, but the maths never worked out. What we did do was get the Magic Camera Company to build some beautiful quarter-scale sails and masts and rigging. We filmed those for elements and shot-specific moments. Then we set fire to it. It was sad, but beautiful as well at the same time. We had these sails all burning and falling apart in a way that you would never have simulated if you were trying to do that on the computer.

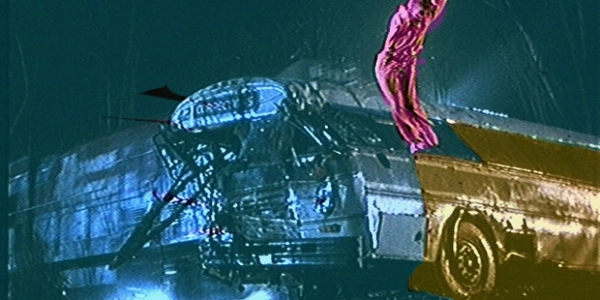

The ice of Austerlitz

During the Battle of Austerlitz, the Austrian and Russian forces are repelled onto a frozen lake, with cannonball fire causing the ice to smash and many of those forces to drown. Industrial Light & Magic handled visual effects for this sequence, drawing upon tank and backlot photography and practical effects from Neil Corbould’s team. Argon crafted previs for the battle.

Charley Henley: That scene was very complicated because it was set up in three different locations and we had to stitch a lot of things together. On an airfield, which doubled for the main ice lake, Neil Corbould’s team dug tanks into the earth. There was one really big one and a bunch of smaller ones. For the tanks, he laid fake ice pieces over there. Then he layed snow all over the area, just tons of paper snow.

Then he had his air mortars in there which allowed us to do these explosions that would kick up water and explode through the ground while everyone was seen running along the lake. It also meant as they ran along, the pieces could collapse and they’d fall through through them on cue. For the horses, they wouldn’t collapse the pieces, but they’d make subtle drops and they’d have a ramp the horses could go in and out of.

ILM (visual effects supervisor Simone Coco) then crafted those ice pieces and the environment, plus they put in a lot of flying ice pieces and matched to the practical ice explosions.

For the shots that are from underwater, we shot in a tank at Pinewood. Keith Dawson supervised the SFX for this shoot. Here they used pieces of wax to create the look for under the ice sets. This was a relatively small area so that had to be stitched together from different plates and then fleshed out. One interesting thing was, we didn’t want to put too much blood in the tank, because it constantly needed cleaning, so we put most of the blood in afterwards.

Ridley took a lot of interest in what a cannonball looks like when it enters the water and there’s all that disturbance behind it. We shot loads of different cannonballs hitting through the water at different speeds. Well, actually, what we did was pull the cannonball through the water to give us that trail of water and air behind it. It looked brilliant. Ridley then wanted to just exaggerate it a bit, to give it an extra distortion of air, and so we would layer that look over the top.

Invisible effects you may have missed

Napoleon contains a vast array of invisible visual effects work. Here’s Henley on just some of the scenes that featured shots you may not have realized were VFX ones, including pigeons and pigeon guano in Moscow, and scores and scores of alight candles.

Charley Henley: For the scenes inside Moscow parliament buildings, Ridley would show us a storyboard and there’d be birds in it! I was like, ‘Oh man, we need to have pigeons here.’ We shot pigeon elements and used those and then also simulated some birds. On set, though, there wasn’t any pigeon crap, so we had to add that. This was both pigeon poop on the walls and floors and chairs, and a moment when one drops while Napoleon is on the throne.

The final kind of invisible effects shot was candles. We had to replace 1200 candles. The reason was, we were basically shooting proper period home buildings, with real 18th Century paintings in them, and a lot of them wouldn’t allow any live flames in there because of the risks involved. That meant there were about 18 fireplaces and then the 1200 candles that we had to put in.

On set, Dariusz Wolski wanted to light the scenes like Barry Lyndon with real candle light. The solution was to build LED candles with bulbs as small as a flame and have complete control of the light, which we test matched to real candle light spectrum. These had exactly the right color tone that gave us this authentic light coming from the candles. Then, PFX took on that job of replacing the candles, and they really became masters of it.