How visual effects in ‘Gran Turismo’ helped tell this real-world gaming story.

Neill Blomkamp’s Gran Turismo is one of those films in which the filmmakers set out to shoot as much of it practically as possible. And, in fact, they really did. All the races seen in the film–which is based on the true story of gamer Jann Mardenborough who became a professional race driver–were shot as real racing on real tracks, with scores of cameras capturing the action.

It is also one of those films where visual effects ended up being relied upon in a big way in several key areas to further enhance the story. These included augmenting and sometimes completely reconstructing race tracks, dealing with crashes and explosions, adding in stadiums and crowds, and removing pod car rigs and camera rigs used for filming race scenes. Fun video game overlays were also part of the mix.

But perhaps the major way VFX came into play was for something a little more unexpected; helping to make the cars appear faster on screen. This saw a mix of manipulation of live-action footage and the use of CG cars to add much-needed dynamism to the final shots.

Ultimately, Gran Turismo would feature 1,156 visual effects shots, overseen by visual effects supervisor Viktor Müller, who shepherded the work by his own company UPP, along with contributions from Pixomondo, Crafty Apes, Zero VFX, SSVFX, DNEG’s motion graphics team and Müller’s L.A. in-house team.

S.P.E.E.D.

As Müller and the filmmakers were reviewing the principal photography of the races, they were certainly excited at having captured so much practical footage from so many angles. However, states Müller, it was clear that “while the cars looked real and fantastic–because they actually were real–they were not fast enough. Or, more correctly, they didn’t feel fast enough.”

Wanting to keep as much of the practical footage as possible, Müller first considered ways of accelerating the plates, or the individual cars in them. “We tried a few experiments with speeding-up the cars, but it didn’t work. We did use this for a few shots in the end, but the challenge was that our cameras were very dynamic, so if you sped up the movement of the camera then you could see this in the shot.”

A second option was to keep a practical car in the frame, but then add in other CG cars to help accelerate the shot. “This was going to be one approach, in any case, since we only had a limited number of cars to shoot with, so there were always going to be some cars added. I would get some nice notes from Neill, saying ‘Make it F.A.S.T’ or ‘S.P.E.E.D.’ when he was talking about the cars.”

In the end, a shot-by-shot approach was undertaken for when a scene needed a CG car replacement to ensure the action was as dynamic as possible. This approach needed to fit in with what was already filmed, including the many pieces of action drone footage shot sometimes at 200 kilometers an hour (Müller comments that matching the motion blur in these plates for scenes with CG cars or stadiums or crowds was particularly challenging).

At one point, too, Müller realized that some of the digital cars were driving at something like 470 kilometers an hour to fit in with the desired cut. “We took them back down to a normal, more real speed after we saw that.”

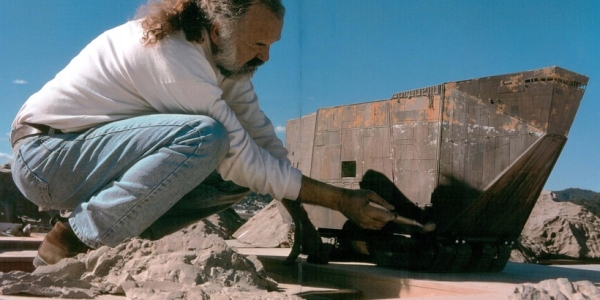

Crafting cars (with baby powder)

In order to make those digital cars (which were also utilized for a large amount of invisible rig and camera removal shots, discussed below), UPP set about scanning the real ones used during production. Archie Madekwe, who played Jann Mardenborough, was also scanned in order to create a digi-double to sometimes place within the CG version of his car.

While Lidar scans of environments and tracks were possible, the same approach to scanning cars proved to be a more difficult prospect, given the reflectivity of car surfaces. Those reflective surfaces also make photogrammetry difficult because the reflections get baked into the photogrammetry itself.

With those issues in mind, Müller commissioned a large white tent to be built at one of the filming stages. “I had done something similar in the 90s when I did a lot of car commercials, where you’d just wear white clothes, you’d put a white cover on the camera so you only had the black lens, and then you’d light from the outside of the tent.”

The approach worked well, says Müller, but there were some catches. The Capa Lamborghini featured in the film was mostly gold. This presented a problem for scanning and photogrammetry. “My scanning supervisor said, ‘No worries, we’ll use this special spray which then vanishes in half an hour.’ Well, we sprayed it, scanned it, and the liquid disappeared, but the shine didn’t come back! Eventually they had to reskin the car.”

“That was when somebody suggested using baby powder instead,” continues Müller. “This effectively puts a tiny grid over the whole car and it means you can scan the detail. UPP then did a stellar job building CG cars.”

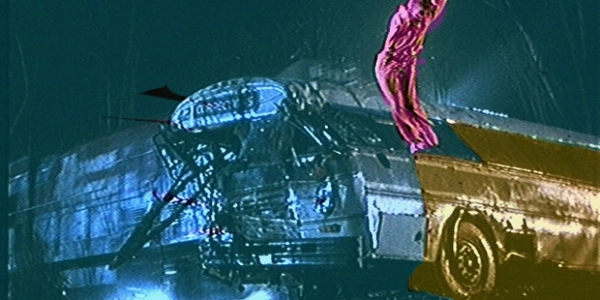

The dynamics of a crash, and the art of bungee cords

Digital cars were also employed for significant crashes, including one involving Mardenborough at Nürburgring Nordschleife. The airborne moment was not one that production looked to film practically, for safety and logistics reasons. That task was left to UPP, who studied the real crash and sought to replicate it one-to-one digitally.

“We started that crash by animating a first pass,” describes Müller. “Then we took everything into simulation. There was no way that I wanted to do handmade animation for the full crash, because if you do that it always looks fake. So we animated a pass, then applied simulation on top of it in Houdini. It gives you all the right dynamics.”

Originally, only external views of the spectacular crash were envisaged. But a note from the studio suggested that it would be good to be in the car with Mardenborough as the vehicle tumbles. This was only about six weeks before delivery, and Müller didn’t think he would be able to deliver such a shot in CG in time.

“So,” says Müller, “we built a special cage construction with bungee cords in Prague and used one of my colleagues dressed in racing gear to sit into the cage. We shook it like crazy in front of a greenscreen and filmed it. I felt it was going to be the only way to get those dynamics, and it was great to have a real element to use.”

Car parts

Car replacements became another area where the digital vehicles were invaluable on Gran Turismo. During filming, several different camera set-ups were employed, some on the sides of tracks and others directly on the cars. These include pod car installations on the top of the race cars, or cameras hanging on the back or on the edges of the vehicles.

The effect of this was that the footage captured the real cars and the real racetracks, but with these cameras and rigs sometimes visible in frame. The VFX teams were then responsible for painting them out or replacing car parts, or even full cars.

“If we had a pod car, for instance,” explains Müller, “we would need to re-touch the driver and the pod from the roof. That meant there were a lot of additional shots which were about replacing things. That’s also where our CG cars came in, for matchmoving, and partial replacements. Crafty Apes and Zero VFX did a lot of these shots, as well as UPP, Pixomondo and SSVFX.

Making tracks and making crowds

One of the other major VFX challenges Müller would face was that while many tracks featured in the film are actually the real tracks, the production was not going to be able to film at Le Mans for the 24 Heures du Mans race scene in the film. This meant no filming, no scanning and no photography or photogrammetry could take place at the actual location. Instead, visual effects would create Le Mans based on racing footage filmed in Hungary and additional CG builds.

“I’m a big lover of Le Mans,” notes Müller. “I’ve been there nine times for the real race and I often take some of my crew from UPP. That meant we had a lot of pictures in our personal libraries already, and then we also searched on the Internet and started building Le Mans, based on those pictures. Then, we had the Hungary footage and we had to modify our Hungary track to look as close as possible to Le Mans, but at the same time fit it into the set of Hungary.”

Other tracks that would require extensions, or grandstands to be built and populated, could be Lidar’d, scanned and photographed. Then came the need to populate tracks and grandstands with crowds.

During filming, some smaller crowds were able to be placed in the stands, but Müller relied on UPP and Pixomondo to tackle most of the crowd replication via digital means, starting with photogrammetry scans of extras. He was also able to film a range of crowd elements for more close-up views on some additional shoot days.

Game overlays

Finally, a specific narrative device was used to connect the real-world racing with Gran Turismo’s video game roots. The shot required an ‘exploded’ gaming car overlay to appear around Mardenborough as he sits in the simulator. That overlay would be made up of hundreds of actual Nissan car parts which would then, in holographic form, slowly begin to conform around him, ultimately turning into an actual race car on a track.

The effect was fully computer-generated by UPP and composited into the scene. Plates of the actor featuring a moving camera were tightly matchmoved, with the various modeled pieces then animated to form around the driver. Interestingly, Müller found that a very early initial render of the overlay was almost immediately successful.

“That first render became a reference to the very end, because when we started to polish it and polish it and polish it, we all realized that we liked the first version better. It was as if the lower-quality render gave it a better hologram feel. I wasn’t sure this effect was going to work, at first, but it’s something that a lot of people loved in the movie.”