Behind the scenes of Moon Knight’s Ammit vs Khonshu battle by Wētā FX, plus the VFX studio’s work on the ‘million night skies’ sequence.

At one point in the Marvel Studios/Disney+ series Moon Knight, Egyptian goddess of judgement Ammit and Egyptian moon god Khonshu appear as 100 meter tall creatures fighting amongst the pyramids. They also battle inside the Chamber of Gods.

These sequences were handled by Wētā FX. In this befores & afters interview with visual effects supervisor Martin Hill and animation supervisor Kevin Estey, we learn about the particular build required for the crocodile-like Ammit, the animation challenges, and the environment work done for Cairo and Giza. Plus, Hill and Estey also break down the earlier ‘million night skies’ celestial sequence in the show.

b&a: Where did you start with Ammit versus Khonshu as giants?

Kevin Estey (animation supervisor): We started working with Ammit and Konshu as their 9-foot-tall characters in the Chamber of Gods before we worked with them as giants. It was good to be able to do that because we got to develop Ammit’s character first, then found ways for that to translate into her behaviour when she was 100 meters tall. [Framestore built the asset for Khonshu and passed that onto Wētā FX].

For them as giants, there were a lot of things that were different, namely the weight, speed, and latency of actions that would happen. There was a lot of push and pull with that because if you really try to create actions accurate to scale, it’s going to be pretty boring and slow. It’s easy to forget the scale too when you’re working in that regard. That’s why it was really helpful early on to use real-world physics alongside the animation so that you are reminded, ‘Oh, it’s taking a long time for that rock to fall.’

One of my favorite moments is where Khonshu pulls up his staff using ‘the force’, as it were. The FX team added all these cars and light poles getting pulled up by the staff, which we didn’t have present when we were animating. It was another effective reminder that ‘Man, these things are massive.’

Martin Hill (visual effects supervisor): As Kevin says, there was a real effort with the dressing that we put in Cairo to remind ourselves of the human scale to contrast with the scale of the Creatures and Pyramids. These shots are fully digital and we went off the previs a bit to bring the cameras down to human height. Ammit is 100 meters tall! If you are only in the air, you only have the point of reference of the Great Pyramid, which is 141 metres. So we tried to make as many shots as we could low and looking up.

Kevin Estey: In animation, we had to be on top of it, too, because you’re often looking at things in simplified environments. So you could easily have the camera traveling a couple 100 kilometers per hour and not realize it. We’d say, ‘Let’s put a few things in front of the camera very close, or let’s get the camera down right on the surface and put a human-scale character next to the camera so we know it’s not actually 100 feet off the ground. Then all of a sudden, you’d realize things that you didn’t notice before because you didn’t have the context.

Martin Hill: The physics simulation was quite interesting because, as Kevin said, when they smash a tomb, the blocks come out flying in a properly simulated space and that gives everything lot of weight and scale. But the characters themselves need to be faster, for the energy of the sequence and the speed of the edit. With the bandages and dust flying off them and Ammit’s dress simulation, we needed to find a sweet spot for secondary animation that’s connected to the characters at the large scale with the speed of the characters’ motion. The cloth and bandages that come off Ammit’s face are now 20 centimeters thick, they’re going to look really odd simulated at that scale.

So we needed to still make them loose, but not as loose as they were at nine feet and still work with what was happening on the ground at the large scale. It meant there were some interesting trade-offs there and we needed to keep in mind both scale and maintaining the excitement.

b&a: For when they’re normal size, nine feet tall, and then 100 metres tall, was there reference shot, stuntvis, stunt performances, or even motion capture that could inform both those separate kinds of fighting?

Martin Hill: Originally, we did plan to have motion capture on set with actors there, and I’m very glad we did. It meant we could put them in costume and they were really good for lighting reference and for eyelines. They had sticks out of their heads with markers so the other performers could see where their eye lines were, but when we got into the performance, it very quickly became clear the strides weren’t correct for the character size. So we had to re-work that from scratch.

Kevin Estey: At Wētā FX, we have a capture stage that’s just around the corner. We can usually get in there pretty quick and capture some motion. I’m a huge fan of capturing whatever you can, knowing full well that you can change it later, but at least if you bank it, you’re going to have a good base. And it’s a great place to play with ideas as well.

Martin Hill: Yes, and when Kevin went in to do the Ammit capture shoot, New Zealand was in COVID lockdown. So, normally Kevin would be there, there’d be a couple of performers, directors, all the motion capture TDs. But for this one, Kevin was pretty much in there on his own.

Kevin Estey: We were just out of a level four lockdown in New Zealand. It was the first day we were able to go on stage, but we were only allowed a stage manager and one other person. Luckily, I have a lot of history doing mocap from way back in the early Hobbit days. So I said, ‘OK, I will play all the roles. I will direct myself in a suit as Ammit and as Khonshu.’

In later shoots when we were able to have more people present, I grabbed another colleague of mine who I’d done a lot of Hobbit mocap with, who’s also worked very heavily on the Apes films. We have a second language on stage, so we don’t have to communicate too heavily, and performance ideas just come naturally with that history working together. We became Khonshu and Ammit for the majority of what we created.

During the first post-lockdown shoot, we were tasked to find a feminine performer for Ammit. I said, ‘Yep, got the most feminine performer we could find…’ which was also the only performer we could find at the time, ‘…me’. During the Hobbit days, I was known to play the odd female elf as well. So I guess it didn’t feel too far off the mark being able to make the performance work.

b&a: This might sound like a strange question, but Ammit is a crocodile–is that right?

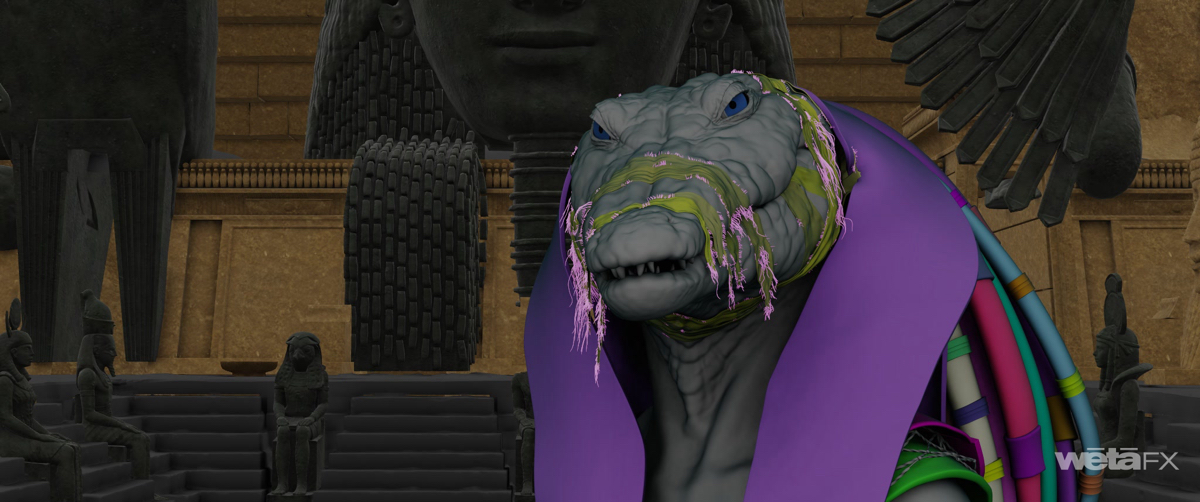

Martin Hill: She’s a chimaera. In the mythology, Ammit is meant to be part hippo, part lion, part crocodile, which are the three most dangerous things you can come across in Egypt, I believe. The first references that we found of Ammit was a quadruped with the forelegs of a lion and the back legs of a hippo. And we were thinking, ‘Well, how does this move?’

We ended up with something that’s much closer to the comics, which is essentially a bipedal crocodile. But that posed a lot of problems in itself because a crocodile’s head is rigid, they’re not terribly expressive. It’s really good when you want the mean evil stare, but we needed to have some sympathy to the expression and she needed to look conflicted at some points.

We started trying to develop the character and find out who she was. And we made a few adjustments, like putting in what are more or less human eyes, which made her a lot relatable.

Kevin Estey: That was actually an interesting shift. We had reptilian eyes on Ammit yet we were working with human voices and thinking, ‘How do we make this feel like a real reptile, but also make it believable that she’s speaking?’ At one point, I don’t know whose suggestion it was, but there was a thought, ‘Why don’t we throw some human eyes in there?’ All of us assumed it would become too cartoony, but we thought, ‘Let’s just try it out.’ As soon as we put the human eyes in there, we all just immediately connected with the character and it was such an important shift that we almost didn’t try.

b&a: Because of the reptilian nature of it, were there any fighting styles or beats of actions that worked better as a crocodile-like character than just as a humanoid one?

Martin Hill: There were a couple. Early on, the fight between Ammit and Khonshu was going to take place near Cairo Tower, which is on an island in the middle of the Nile. We looked at a lot of references of crocodiles flying out of the water. A lot of that turned into a prehensile tail, which she could use and control. There’s a whole shot where she grabs Khonshu, which is inspired by a crocodile roll. She bites him and then flips him over, which was pretty fun to do.

Kevin Estey: One of the significant aspects of her physicality is that her tail is fully attached to the back of her head. It contacts, but it does not come out of her back at all. So there was a lot of discussion around how the tail actually functions since it’s essentially a ponytail, but it turns into a ‘tail’ tail at times. The methodology we developed was to ignore the fact that it was attached to her head so it would behave independently unless we wanted it to coincide with what her head was doing. There was the occasional head whip and other head-motivated tail moves. But other than that, the tail functioned as if it was coming out of her back, even though it wasn’t.

Martin Hill: There was a conversation at one point of, ‘Well, does she have two spines? What’s going on?’ Originally, it was an entirely reptilian tail coming out of her head, to the point where if you decapitated her, you’d pretty much be left with a snake. But after a little while, when we got more into the design, we changed a lot of the reptilian stuff, the top of the head, to more of a mummified braid or plaits of the hair. There was then some ambiguity about whether it’s hair or whether it’s a tail.

Kevin Estey: Another of the biggest aspects we worked on throughout all of this development of the character was the believability of her speaking. A critical notion was trying to develop lips for her that looked 100% legitimate to what a real reptile would have, but moved in a way that was convincing of her vocalizing and creating phonemes and sounds with her mouth. A big no-no we wanted to avoid was clapper board movement of her mouth. It was very easy to fall into that type of movement with heavy dialogue because that’s the only thing the mouth really can do on a creature like this.

I think we got upwards of 100 versions of just one line of dialogue trying to work on how much or how little we move the jaw. We ended up with a less-is-more approach. We have a history of working with long-snout characters who talk, like Smaug, where we learned a lot about making convincing phonemes on an elongated mouth. What we learned with Smaug and even more so with Ammit is that you want to focus the audience’s attention on the front of the mouth. Everything that’s happening at the back of the mouth just aids in what’s happening up front. You essentially have to divide the mouth into three components so you’re almost doing triple the work than you generally would with lips, as you’ve got a front, middle, and back.

In fact, I remember a discussion before we convinced everyone of the believability of her speech, that she might just be shrouded in smoke and darkness if her speaking wasn’t convincing enough. I guess we gained enough confidence to put her out in front and in the light, which was great.

Martin Hill: All that hiding her in smoke went away once we did the dialogue test which showed we could make her talk convincingly. Subtlety of motion was the key, but we also found with all the scales and paint on her head, and the gold leaf and all the bandages, acted as camouflage which detracts from the broader shapes and made the dialogue harder to read. It was about finding that balance where we could read the motion with all that detail on there.

Kevin Estey: On the notion of subtlety, there was a lot of care and attention put into head angles. Not only could you gain a lot in terms of attitude and expression from just doing a small head turn, but there were also some no-no’s with her head angles. Front on and straight down her nose was not a good angle. Often, we found that seeing one eye versus two was much stronger because you could get a lot more expression from one eye. Additionally, with her eyes being on the sides of her head, it was tricky to create convincing eyelines. I think if you ever looked at any of the shots with a camera rotated 45 degrees the other way, her eyes would not look right. You had to really play to the camera constantly to make it look like her eyeline was accurate.

Martin Hill: With the eyes on the side, if she was looking forward at you, it was very easy to make it look cross-eyed and that was something we took care to avoid.

b&a: What about the environments? Here, you’re placing these huge characters into the pyramids, how did you approach the environments here?

Martin Hill: When we first started the show, the plan was to shoot in Egypt, and for various reasons that went away. So we were then presented with, ‘We can’t shoot Egypt and we can actually only get very little reference in Egypt itself.’ Remember, our director’s Egyptian, so there’s nowhere to hide. He clearly has an in-depth knowledge of the city and a very clear idea of what he wanted as well. He didn’t want Giza to look like it is some pyramids in the desert, he feels like that’s how it’s often portrayed in films. He wanted to portray Cairo as the modern, vibrant city that it is. So accuracy was key.

The first thing we did was look to what was available through open source data sets. Cairo is one of those cities that is so heavily photographed. It’s actually really hard to sort the wheat from the chaff and find decent reference where you know what the camera data is. So you can’t just Google, ‘Give me Cairo images’ and throw them into a photogrammetry tool. We went to Maxar, which is a satellite imaging company, and bought a 10 kilometer square area, which was from Giza around all the way to the Cairo Tower. It had DEM data but also different angles. That was pretty good in terms of far backgrounds that we could project on and add moving cars and lights to give it some life.

Kevin Estey: Having that real-world context really helped us try to figure out where they were going to end up, what side of the pyramid she was leaning against, for example. That’s not to say we didn’t take liberties on a few occasions and maybe moved the Sphinx as we needed, just for composition purposes.

Martin Hill: We shuffled around a lot of the tombs from where they were standing as well, to make the shots look interesting. But for the rest of the city–they were shooting in Jordan, so we scanned a whole bunch of buildings there and also found some Cairo-like buildings, some mosques and minarets. We also built this library of dressing for the rooftops and streets of some very Cairo-specific things, some very Cairo-specific colour palettes. There are lots of pigeon coops on the rooftops and washing lines, and lots of building materials all over the rooftops there, which really helped give a high level of detail.

In the marketplace, we utilized some buildings from Budapest where the stages were, which fitted in with the colonial area of Cairo. What we’re always very cognizant of is putting the right buildings more or less in the right place in Cairo. Then when we put the shots together, it was a case of, ‘Well, let’s rotate this mosque around a little bit…’.

One of the things for Giza itself was that we started placing a bunch of gack around, particularly the archaeological work lights, and it was a great compositional tool that we used to draw the eye and map out how we want the viewer’s eye to move through the shot to complement the animation.

Kevin Estey: Once Martin started adding those work lights, I remember that’s what really made that sequence pop. Those work lights, for some reason, just really brought it all together for me. It added that contrast and warmth against the cool moonlight. And it gave a chance to get in some underlighting, which gave them a real sense of scale.

Martin Hill: We also got to smash them, which was fun as well!

b&a: There’s also the Chamber of the Gods work I wanted to ask you about.

Martin Hill: I really enjoyed the Chamber of the Gods because it was this fantastical interior that drew from the ancient architecture. You can go around and find all this museum reference and archaeological dig reference. It’s just really fascinating for me when you start to work on shows like this, how you can do deep dives into subjects and use that to really inform the work. Although, one thing I would say is the Chamber of the Gods environment doesn’t fit inside the Great Pyramid. It’s actually slightly bigger.

Kevin Estey: In fact, I had to learn that the hard way because there was an early version of the shot that unfortunately got cut down to roughly a 5th of what it had been. There’s an establishing shot of outside of the Giza complex, the pyramid’s at dusk, with the sun setting behind it. It was one of the first shots I had worked on, and it was a good 20-second shot that started down on the floor of the chamber and pulled all the way up into the ceiling.

Then the camera travelled through the inside of the walls of the pyramid and ended up coming out of the walls through a small opening, slowly revealing that this was all inside the pyramid. There was a lot of work and development done on that. I was really proud of the collaborative process we had.

When I was setting it up, Martin said, ‘By the way, the environment you are starting in doesn’t fit inside the pyramid we are coming out of.’ So we had to figure out a way to make this work. I had to at one point move the inside environment away so that we didn’t see it when we exited. And it’s a shame none of that got to see the light of day. I was really excited about that shot as the full-length version was very effective.

Martin Hill: It did look really good. It was a wonderful combination of filmic cheats. We were going through these air shafts and so we looked at pyramids and looked at the angles of those shafts and made sure they were correct. We made a real representation of the Queen’s chamber looking from one angle that we flew past. And then the bit that we came out of, there’s an entrance in the Great Pyramid called the robbers’ entrance where tomb raiders, I guess, years ago broke in and raided the pyramid. We used that as the exterior. It was really nice finding all these elements and combining them in a way. It was really exciting. But then it got cut, unfortunately.

b&a: Tell me about the million night skies sequence, and how you started with any look development on that.

Martin Hill: We got involved really early on this sequence. Framestore was doing the previs of the characters and the blocking of the scene. They had some rough ideas of what they were going to do with the sky, but what was really cool was getting involved early so we could actually work out the timings and light the actors on the stage with what we planned to do. This also meant a lot of the work was done beforehand, similar to if you were working on a virtual stage.

We needed to tell the story point of Layla and Steven having found this celestial map where the stars point to the MacGuffin, but it was created at the time of the pyramids. So the stars have misaligned and they need to wind back time so everything’s accurate. Khonshu and Mr. Knight then go forward and also wind back the time and the constellation so everything lines up. Our thought was, ‘Well, we know we need to spin back time. What would actually happen if we did this properly?’ And by properly, I mean, with some semblance of physical correctness.

So, we built a pretty plausibly-accurate earth, moon, solar system, and then galaxy model, and then inverted all the rotations, so Cairo at its 30 degree latitude was at the origin, and then started spinning back time. We used an astrophotography app to validate everything we were doing.

It turned out that there were a few interesting things that we discovered by doing this which went into the final piece. This included the libration of the moon, the way it rocks on its axis. It’s not just perfectly locked to us. When we had the frame rate of one lunar day and lock the camera, we found the motion of the analemma of the moon, which is a big figure of eight, we put that into the final sequence.

Still, we weren’t tied to, ‘This has to be absolutely accurate.’ We’re making a piece of entertainment, so it was really a case of the final piece being inspired by the physics. We also added in glitches and supernovas.

Kevin Estey: I remember that being the sequence you were working on when I joined the project. We talked about the glitches as a reference to Fight Club when visuals start to stutter and lose focus. We also discussed the notion of being in the desert and references to The Doors, peyote, and heightened visual influences where everything is surreal and overly vibrant.

It was one of those rare sequences where Martin’s team’s work had to be nearly complete before we could get buy-off on the animation because the characters were controlling the skies. It was a tail-wagging-the-dog-type approach, which was a really, really cool way to work.

Martin Hill: What I love about the glitches is that normally we’d be talking about little camera shakes, but here we’re talking about inaccurately capturing the whole Earth’s rotation. Kevin would also be adding in all of this muscle tension into Khonshu and Mr. Knight’s arm that was in sync, having that same energy between them so you could really see that they were driving what was going on in the stars.

b&a: What I really liked about it was it also evoked some of those long exposure light paintings that I’ve seen a lot of done in the Australian desert, say.

Martin Hill: Yes, one of the first things we did was look at astrophotography and long exposure photography. It inspired a lot of lens choices, too. One of the things about real astrophotography compared to what we were doing was that we needed to go over only the 12 hour night period of the moon. So we just ignore the sun, which is quite difficult to do in real photography. Otherwise, the whole thing would just be a complete strobing mess.

b&a: What were you doing during the shoot to aid in interaction?

Martin Hill: We’d made the orbits of the star fields and the trails of the moon, so we had the timings of them. When we had a six panel LED rig for lighting the on set characters, we thought, ‘Okay, we’ll be using this section for this particular shot, this section for this shot, etc.’ It meant that the timings were correct, and we knew what sky they related to. Going full circle back to lighting Khonshu as a digital character, we had synced witness cameras on each of those panels, so we could sample the lighting intensity at the different spatial positions, and then they could relight the characters. Our CG supervisor, Ross McWhannell, did a really great job of putting together a system that brought in all those witness camera references and essentially concatenated them down to create a light rig where it would get all that timing for us.