Well, that’s basically just one thing Weta Digital had to do for ‘The Suicide Squad’.

If you haven’t yet seen the major end sequence in James Gunn’s The Suicide Squad, you might want to stop reading right now. Let’s just say it involves a giant alien starfish called Starro and a LOT of destruction. Which meant that the filmmakers, including production visual effects supervisor Kelvin McIlwain, called in regular climactic sequence creator Weta Digital to orchestrate a ton of large-scale animation and effects simulations.

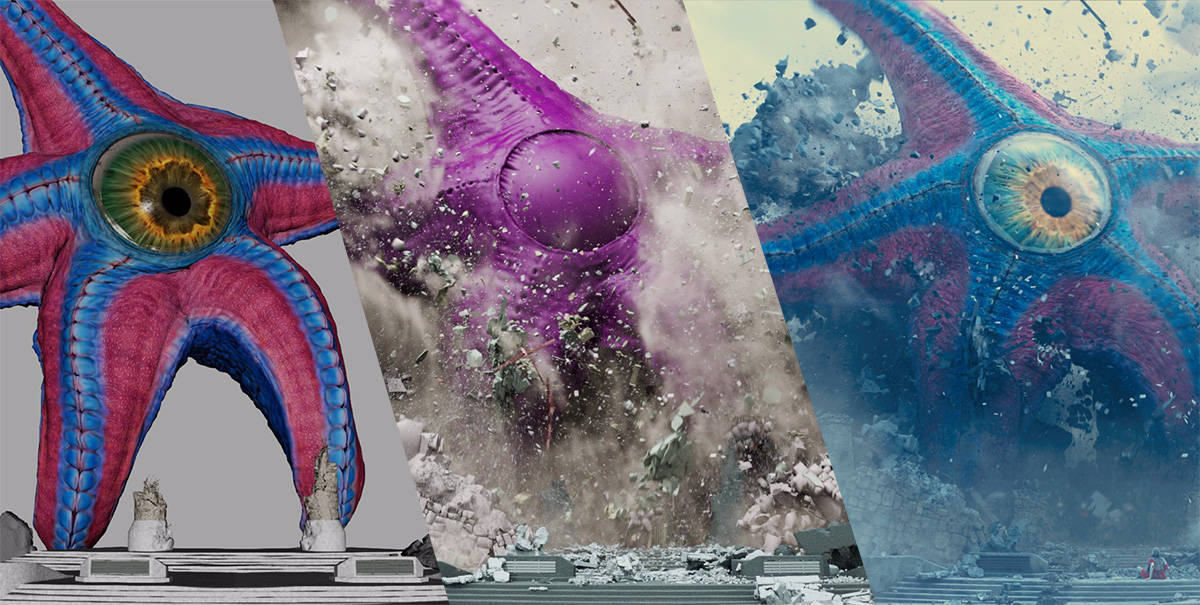

Here, visual effects supervisor Mark Gee and animation supervisor Mike Cozens– who worked alongside fellow Weta Digital visual effects supervisor Guy Williams– explain the Starro destruction scenes, making note of the AR app used during filming, the build process for the creature and the buildings, the behaviors that Starro needed to exhibit, and the particular approach to FX sims that allowed for so many different materials to be sim’d together.

b&a: I wanted to focus first on that destruction scene of Starro walking around. Where was that filmed and what kind of set up was there for that?

Mike Cozens: The scene where Starro emerges from Jotunheim was shot at Pinewood in Atlanta. There was a giant exterior set of the Jotunheim parking lot in various states of destruction as well as numerous interior builds. The exteriors where Starro walks through the city were shot in Panama. From my end, the biggest question going over there–as we saw the work and what needed to be done–was how to bring an idea of the scale of the creature to the crew. Working with one of our visual effects supervisors, Keith Miller, we developed an augmented reality app on an iPad where you could use the iPad camera and place a digital version of the creature into the shot, locked to the environment. You would be able to look at the street and you could frame up for the 150 foot creature with the iPad, and track the creature as he moved. We got it working with some basic walk cycles before we left for Atlanta.

What you’re really trying to help with onset is shot construction. You want to understand the speed and size of a creature like that. Having a visual representation that we could take with us, and even thought it was a very early version of the creature, informed the shooting and got the actors and crew excited about the character.

James Gunn is all over his storytelling. He knows what he wants in each shot because he has crafted his storytelling through his writing, the boards and the previs. We did have an opportunity when showing Starro in the app that James and Henry Braham, Director of Photography, came up with a new shot of the creature travelling over Harley and the squad. It was great to be providing solutions on the day.

b&a: Mark, for the scenes in which Starro is really causing havoc on the buildings, where did Weta Digital start with its destruction work?

Mark Gee: Our FX team experimented with various FX solvers to destroy these buildings. We built the building exteriors to start with, before adding interior walls and floor details and including structural components like columns, trusses, joists, and rebar. Finally, we dressed the buildings with furniture including curtains, tables, chairs, and other various pieces. Jotunheim tower was actually built brick by brick, floor by floor, and like the other destruction buildings, we populated it with various interior structural components and dressed it with office furniture and fitting. All of this additional detail not only gave us realistic destruction behaviour, but it also added so much more visual detail and interest to the sims.

Some of the biggest challenges they had were simulating all those different material types together. You’ve got a variety of physics solvers in Houdini that all have different strengths, but they don’t interface well with each other nor scale well to very large datasets. So FX Supervisor David Davies worked with FX Destruction Lead Rogier Franson, who came up with an approach of using the Bullet rigid body solver that’s integrated into Houdini to simulate all the various different material types together. So, the curtains in the buildings would still be able to react like cloth, but also simulate and react to other material types like breaking concrete and the splintering wood which would in turn react with each other.

We spent a lot of time working with the concrete slabs and debris that broke away and came crashing down during the building destructions. FX used a staggered approach where the primary sim featured only larger objects. Constraints from the primary sim were analysed to add additional chipping and fracturing detail only around the impacted areas. This really sold the reality that the objects falling were massive pieces of concrete and made the impacts far more believable.

There’s also a scene where our heroes are running along a linoleum tiled floor as they try to escape a collapsing building, and each of those tiles react to the underlying concrete breakup. Creating a believable result would have been much harder to achieve if we weren’t able to sim those material groups together with the same solver.

And Animation did play a big part in that, because they blocked out the timing of the basic destruction, which meant we were able to get director buy off on the destruction blocking even before FX did any simulation work. This streamlined the whole FX pipeline which was vital due to the amount of destruction we had to do in such a short amount of time.

b&a: I’ve always been interested in that, Mike, the relationship between anim and FX sims, or effects artists doing stuff in Houdini. I mean, do you start something, do they also start something?

Mike Cozens: It’s a good question. There are parallel bits of development happening between the FX team and Animation. Animation is trying to answer the shot construction: what James wants to see inside the frame and when. We are chasing the storytelling over the series of shots. We work roughly and quickly so we can turn the ideas around fast. We are breaking stuff in animation and modelling stuff in animation so that we can quickly represent the idea of the shot and show that to James for buy-off.

To keep the turnaround fast and to answer those questions quickly, it’s what we call working dirty, which is basically that the work is all throwaway because it cannot be passed down the pipe. However, it answers a lot of questions. And you can imagine when you have shots that needs a lot of digital support inside the frame, you need to represent that and understand what that is early on before the FX artists are in there making it look beautiful.

b&a: And Mark, a subsequent question to that. What does Kelvin see, or what does James see in terms of early anim for destruction scenes? Does he also see some gray shaded effect sims? I’m always interested in the review of these assets and shots by the filmmakers as they get made.

Mark Gee: It’s a very layered approach. Animation essentially blocks out the motion and timing of the FX using low-res geo for the destruction. And then FX would do their basic FX blocking pass of it using the animation to drive the simulation. At that point, we would send a version to Kelvin for feedback, and if he thought it was important to show James, mostly at that stage for story point or editorial feedback, then he would.

The turnaround times in FX are quite fast at that stage. We were able to do multiple iterations within a day. And once that was bought off on, we’d kick off a higher res and more detailed sim simulating all the material types together, which gave us all that lovely detail that you see in the final shot. These were longer sims, that were generally ran overnight, and some of the more complex sims would run for days. But the fact that we were able to have an FX blocking stage, saved a lot of time in the initial stages.

Mike Cozens: The reviews depend on what you’re trying to answer. So from the animation side, we’re trying to answer what’s in the shot and when, and so we would show the previs or postvis of this work. And then as it spins up in the FX side, you even have more diagnostic looking versions early on, where you’re just testing FX work. Then you start getting it into shot and presenting it for the finely tuned FX work, since by then we’ve answered the questions of what the shot is about.

b&a: Let’s talk more about Starro. Mike, I always like going back to the beginning and what sort of discussions and tests and lookdev you did for the behavior of a walking starfish.

Mike Cozens: I spent a lot of time at the beach, Ian.

b&a: [laughs]

Mike Cozens: We wanted him to feel big, and so the early motion tests were all about scale. The early tests we presented him as massive and slow-moving but over the course of the production we realized he needed to get faster and have more energy as he starts tearing through the city.

We wanted him not to feel like a guy in a suit. It’s a starfish. We didn’t want to put legs on him, we wanted his locomotion to feel like a creature trying to walk on tentacles. He’s sort of like a rope-rig kind of creature. He’s just a bunch of ropes, five ropes. We were playing with walk cycles early on, and that was some of the work that we took to Atlanta with us to show with the AR app.

Then from there, it evolved into other motion tests of him, like him climbing out of the Jotunheim, him learning how to walk forward. Destruction played a big part in all of that. Visualizing and mocking up the destruction, not only of Jotunheim, but of other hero shots through the city helped support his performance. Again, just to give him scale and to understand how big and how quickly and dangerous he was when he moved.

A lot of that work is built up in animation vignettes and then turned into shots or pitched as shots. It’s an exploration that happens over the course of post-production because sometimes the direction for the character changes as the needs for him evolve. When James and editor Fred Raskin are looking at the cut and need more energy, sometimes the dials get turned up or down. And the Animation team are chasing that through the course of post-production.

b&a: In a lot of animation for a CG creature, if it’s humanoid or even an animal, you might try and shoot some vidref of yourself, or even mocap. I’m not saying a starfish can look like a human, but there’s a side of it where I feel like James or you could express what’s going on with your bodies. Is there some ridiculous vidref around like that?

Mike Cozens: With a bunch of animators there is always ridiculous vidref around, Ian. Whatever you’re doing, whether it’s a digital human or a giant walking starfish, it needs to be integrated into a live action plate and be believable. We didn’t want him to move like a biped, like he had legs. You’ll see a shot where he tumbles forward as he’s learning how to get on his legs, and there’s some different style of motion in there as he progresses through the city. There is some strange reference done by the animation team to problem solve some of his performance.

A lot of the exploration for him was done with the intent of what we needed in terms of storytelling through the course of that sequence. So when he needed to be threatening and when he needed to be dangerous… and we built a lot of his action around capturing that.

b&a: In addition to the gross animation that’s on Starro, what were some of the things that helped perhaps sell him in the shots?

Mark Gee: One of the things was the level of detail that we went to in the model and on the look development. Starro had to hold up to close scrutiny. We had shots where the camera was less than a metre away from him, so we had to work out a way that we could shade him so the skin would hold up to a crazy level of detail as well as work for the wide shots. Models got us a lot of the way with sculpting the finer details of Starro and even going as far as modelling the fibres in the iris of his eye with curves.

But it was the work that the shader team did that pulled it all together. Shader writer Artur Vill worked out a way to grow all the blisters on the skin procedurally as well as finer detail such as wrinkles. Adding to that, we used a second surface that looked like the blisters were constantly shedding old skin with additional dirt and decay layered on top. We also ran dust sim on Starro as he interacted with the environment and destruction, which really helped sell the scale and sit him in with the live action photography.

b&a: He had to look evil, and I thought there were some great moments where he’s like clenching himself, and then there’s his eye as well. How did you approach that side of things?

Mike Cozens: Well, he has a very different set of anatomy to work with. He has mouths on his legs with tinier mouth, or throats, inside there. He doesn’t have an eyebrow to make him look mad or anything. The construction around the eye is quite rigid. He had a scaly outer ring around that eye socket. In terms of the eye, it was, in a way, quite simple. It could look around. To make him look ferocious we leaned into what we could do with the body posing, and what you’re describing, which is he gets quite rigid, like he’s holding tension in his body in moments where he is roaring. And doing what we can with the mouth as well. So again, I think a lot of that stuff comes through in posing and in the performance choices that we make in shots.

It was interesting because the legs move like jointless tentacles, but a lot of the surface detail is solid, stony and scaly. There were some issues trying to make that all work and play nicely together and building it in a way where there are soft areas of tissue between the harder surfaces to give us a range of motion that works with the performance.

b&a: I was going to ask you both about, is there a shot or part of the sequence that was particularly tricky when you got into it, but that you were really proud of in the final result?

Mark Gee: For me, it was the definitely the some of the more challenging destruction scenes. James Gunn had something very specific in his mind to what these scenes would look like and how they would play out, so it was a great creative challenge for us.

I think the scene was where our heroes are trapped inside a collapsing tower. They were trying to escape and out run the destruction which was happening right under their feet, and this would definitely be the one I’m most proud of.

The whole team did an amazing job on that, and it’s a sequence that certainly had some unique destruction elements that hadn’t really been seen before. We were also cutting between the actors and their digi doubles across that scene, and it was so seamless that neither Kelvin nor James realised that we went digi until we actually told them at the end of the production. There was certainly a lot of work that went into that scene, from all the departments – it was a team effort and the final result was something everyone could be proud of.

b&a: What about you, Mike? Was there something that stands out?

Mike Cozens: The finale with Starro was quite tricky and very complicated, just because we have not often simulated crowd on top of a creature like that before. We typically simulate crowd on a surface, like a layout. Or if it’s a plate, there’s ground terrain that is picked up off of the LIDAR on the day, and we simulate crowd on those surfaces. In this case, we had plate and we had layout and we had matte painting and we had destruction–moving destruction–and we had a creature, and we had to move crowd over top of ALL of those surfaces.

So all of those elements had to be bought off on before we could get the final crowd working. We also had to figure out a way of pitching James the crowd work early on so that he could understand how the storytelling of the sequence of shots was going to build. We needed to figure out the amounts of crowd, where they were and what they were doing in each moment. And again, when you have a bunch of departments that are dependencies for the shot construction, it’s aligning all that work in a way that lets you hit delivery dates for even a blocking target. That was the complicated part. There’s a lot of chasing down of the individual elements to get things to a place where we could even show rough versions of the shots.

Again, simulating stuff on a creature is not typical. We had to do early versions of the crowd sim on a low-resolution puppet and then change the crowd simulation to work with the final bake of the creature once the creature is simulated. On the final simulation of a creature’s skin there’s muscle and facia moving the skin, and displacement on the skin surface that moves where that surface is. We need to lock all this down to get the crowd connected to it. there’s just a lot of complexity for the crowd work. Really cool shots to look at, but yeah, they were complex to build.

Awesome! Next thing to talk about is King Shark.