The director’s follow-up to ‘The Witness’.

Alberto Mielgo stunned audiences with his animated short, The Witness, which was created for Netflix’s Love, Death & Robots. It was hard to describe what it was, offering a subtle and surreal CG animation and also painterly experience.

Mielgo is back with the equally surreal The Windshield Wiper, a personal tale about love and relationships that again highlights the director’s unique style of filmmaking. He spoke to befores & afters about how it was made.

b&a: Thanks for making the film, Alberto, I really loved it. It reminded me of sometimes when I, before the pandemic, found myself in different countries for work and I suddenly step off the plane and I’m like, ‘How did I get here?’ And I was doing five countries in one trip. It really felt like that to me.

Alberto Mielgo: Thank you so much. You mean because of the variety of landscapes?

b&a: Yeah.

Alberto Mielgo: Okay, okay, okay, cool.

b&a: And sometimes, those trips included Europe, back to Australia, jump over to Hong Kong and just such varying landscapes. Is that what you were trying to go for?

Alberto Mielgo: Yeah. All this reflects places and vignettes that I’ve been, either sometimes where I was living or where I was going there for work. I wanted to represent an international love, per se, for what’s happening all over the world, which is similar. When you go to a city, people wear the same clothes, listen to the same music, and that’s the kind of relationships that we are talking here. If you go deep into the towns, still you feel the difference. But in the cities, except for the landscape and the style of the buildings, the people look very similar.

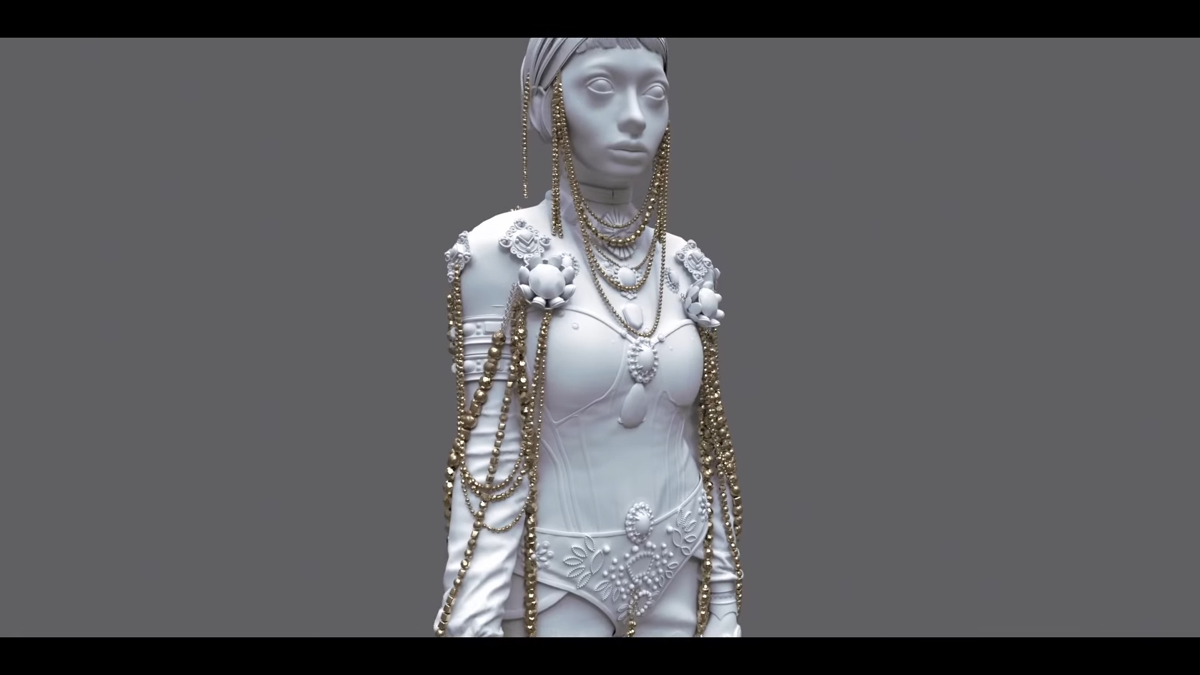

b&a: The reaction I get from this film, but also from your other work and The Witness, is it’s so ‘real’—I actually feel like I’m there. But, you control the detail with your painted backgrounds, the characters themselves, and then the animation. It still feels real, but not in the same way that a live-action film is, and not real in the way that sometimes animation can feel ‘too’ real. Can you explain that?

Alberto Mielgo: It is hard to explain, but I think I have the key of it. We have something that is called uncanny valley. Sometimes animation is so real that it feels weird. But I think that what I usually do, my art is based on impressionism, which is basically what you can catch with the hint of an eye. And the eye is very delicate, and in fact, it only focuses on whatever you are looking at. Anything else is vague.

So with impressionism, what I like is that it looks real, but it’s only details, only what is important for the eye to complete the image. When you do that, and it’s something that is very important in my art and in my career, you make a better experience for the eye. You create compositions that need to be clear, but just with the hint of the eye.

When you see all these films that are CGI films, that they’re full of details—pores, hairs, etc. Everything feels overwhelming and sometimes it’s very difficult to read. I think that in order to be away from the uncanny valley—I didn’t actually do it on purpose, it’s just the way that I learned from painting, I don’t know how to do hyperrealism, for example. I don’t know how to do these super detailed brush strokes that you cannot even see the brush stroke, that is, ‘Is this a photograph?’ I don’t know how to do that.

I guess that’s what you’re feeling. And then I apply that to everything, to the characters, to the animation, to the colours. Everything is like a simplified version.

b&a: While that’s the look of the film, what’s your process in telling the story? Because all those vignettes, they totally meld into a really powerful story, but I’m actually really curious what you have in your head, say, as a script, as boards, as an animatic, or just paintings? What is your actual process for putting this together as a story?

Alberto Mielgo: To be honest in all the projects that I’ve been directing, I work completely different depending on the circumstances. For example, the last project, because of COVID, I had to do all the storyboarding first and then I went on location. And then I was trying to match or to find the shots that I was drawing, which is an interesting process. The other way around, in The Witness, it was completely the opposite. I wrote the script and then I went to Hong Kong and then I found all my shots and I was planning everything there. And then I did the storyboards after, based on the locations and the camera angles that I was choosing on location.

But for The Windshield Wiper, it was a mix and match. It was a mix of the two process. A lot of the locations came up first and then I was doing my storyboards. And some others, the ideas, they come up first and then I have to storyboard and find a location for me to paint to match that moment.

b&a: Sorry if this is a really dumb question, but is that painting you’re doing, is that in Photoshop or Illustrator or is it more actually hand-crafted?

Alberto Mielgo: Actually, handcrafted in Photoshop is actually the same as handcrafted anything.

b&a: Yes, of course.

Alberto Mielgo: It’s basically the same. I actually learned how to paint in Photoshop and then later on I start doing oils. Everything is Photoshop. Adobe is cool because you can use Photoshop and then you can mix it with After Effects and then with Premier and then you can be in a loop, which is something that is very, very useful for my art.

b&a: And then when you collaborate with others, with individuals or studios, how did that work for this film?

Alberto Mielgo: In terms of the art, I do the art myself, the character designs. The environments in this case, I was painting them all by myself. In other films like The Witness, or the one that I just delivered, or a commercial that I did, there is a school of artists that either because they’ve been followed my art from before, or maybe because I trained them in previous projects, we all kind of have a similar style. So now I’m able to grow myself. Perhaps before I was doing a hundred percent of all the paintings, now I can make longer projects and maybe do 50% of the paintings or even 25% of the landscape paintings, and then have amazing artists that help me, creating a similar style. The bigger the project, the way more team you need and the more prepared they need to be in order to match any specific style.

b&a: Another really obvious thing I reacted to in the film was the sound design. In terms of the cafe conversations and then the song choice. I just really want to know how you came up with those things.

Alberto Mielgo: Think you so much. The inside of the cafe, what I wanted is to have a person that is wondering in a philosophical but very simple way, ‘what is love’, and trying to find an answer and everything comes triggered by some conversation that he’s overhearing. And the way that I wanted to do it is I wanted it to feel very fresh and almost like an experiment. What I did in order to capture the cafe, the cafe voices, I invited three men to a dinner and I cooked for them and then, I asked them six specific questions. Another, separate day, I inviteed three women. I cooked dinner and then I asked them the six specific questions as well, because I wanted to hit specific moments.

I was really amazed how the three men and the three women they have completely different answers, completely far apart. Mens and womens needs in terms of love, they are extremely far apart. That was really cool for my point. It felt very natural because it was people basically improvising, being natural in front of a question. That was how I did that. Of course, there were some other parts that were traditionally scripted and acted out.

The choice of the music, the last song, which is a Soko song. I’ve loved her music for a long time. I remember I was actually using that song in the storyboards in the very early stage, six years ago. The music is very simple. It’s basically just her with her voice and a guitar and few other instruments there. It felt perfect for wrapping the film. The other music…she’s a friend of mine. She comes to my place and plays guitar very often, she’s called Lera Pentelute. She’s lovely, she’s a multi-talent and she plays the guitar sometimes when I am there and we recorded it and it felt really cool because it can feel like somebody playing in the apartment, it doesn’t feel like it’s on a soundtrack.

Director Alberto Mielgo reveals all about those crazy visuals in ‘The Witness’

b&a: And just finally, one of the fun things when we talked last time about The Witness was some of the reaction to it was, ‘Oh my God, is this motion capture or roto-animation?’ because it was just so realistic. There are some moments in this new film where I had that same reaction, like the homeless man or a few of the other characters. Is there something you can say about, again with the realism or hyperrealism for the animation, which is actually very subtle, there’s a lot of subtle movements. Even the man smoking is just very subtle.

Alberto Mielgo: Usually animation, just because of the nature of movement, needs to be exaggerated, especially cartoons. I suppose that it comes from the times where there was not even talking. It was just actions of Mickey Mouse being naughty, which was the beginning of animation. Mickey Mouse was an asshole, apparently. It was not for kids. The nature of animation is exaggerated moments and I really like subtle. We don’t move that much, I mean, people. I’m an expressive person and maybe I move my hands a lot, but usually you keep yourself in the place. There is no need for over-anticipated movements or constantly having your character balancing which is what is happening a lot in mainstream animations that they are perhaps for families or for kids.

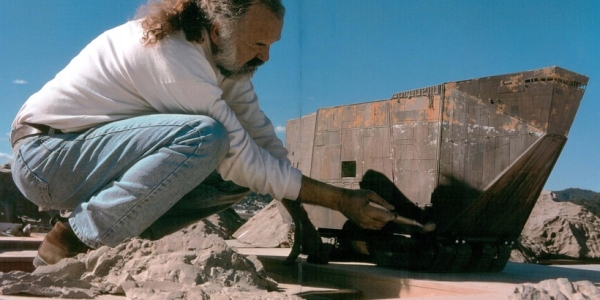

As we were discovering the animation in this film, I was basically shooting myself and shooting a lot of friends as well for the female roles. I was giving these as reference for the animators and I would say, ‘Follow this as close as possible because this is the right timing and this is what I want.’ Sometimes the characters they are still and they basically breathe a little bit and that’s good enough. We don’t need more, especially when the subject is this realistic and this, perhaps, mundane, I would say.