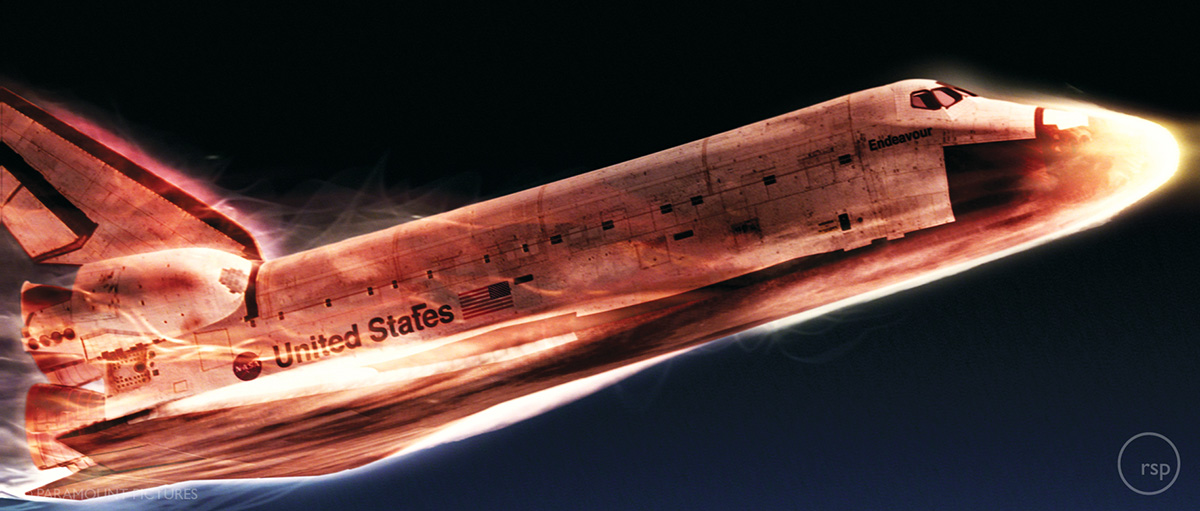

Looking back at Rising Sun Pictures’ wild space shuttle crash-landing for ‘The Core’.

In 2003, I was at a visual effects festival in Melbourne where Rising Sun Pictures’ Tony Clark, Ian Cope, Ben Paschke and Dan Kripac presented on the studio’s space shuttle crash-landing visual effects work for Jon Amiel’s The Core.

The thing I remember so distinctly from back then was an audible gasp in the room when RSP showcased the final shot from the landing sequence in which the shuttle – now ‘safely’ downed in the LA River – dangerously approaches a worker on scaffolding, stopping just in time. The audience applauded Rising Sun’s CG shuttle work and the lengthy rotoscoping involved in compositing the asset behind all that scaffolding.

So, when I heard Rising Sun Pictures was celebrating its 25th anniversary this year, I thought it might be fun to look back at that killer work from The Core with some of the team involved at the time. It turns out to have been a milestone movie in the studio’s history, being something much more complex than they had handled previously, and paving the way for how the Australian-based studio would deliver work and communicate with VFX supervisors on future projects.

How Rising Sun scored The Core

Greg McMurry (visual effects supervisor, The Core): I had done Queen of the Damned (2002) with Rising Sun, which we shot in Melbourne. We really hit it off, and I’ve worked with them ever since.

Tony Clark (visual effects supervisor, Rising Sun Pictures): Red Planet was the door opener for us working on big American films. We then got connected with Greg for Queen of the Damned. That was a great experience and then we went on to do The Core.

Tim Crosbie (digital effects supervisor, Rising Sun Pictures): The brief was pretty simple, ‘land the space shuttle in the LA river.’ The details, however, took time to get right as they always do when we’re seeing things up close on the big screen. We all enjoyed ourselves because it was such a great little sequence, lots of eye candy and a lot of fun to watch.

Ben Paschke (lead 3D artist, Rising Sun Pictures): We had two offices at the time, Adelaide and Sydney, and it was a joy to complete the film with excellent cooperation between the two offices. But perhaps the most greatest memory for me was being flown to Los Angeles to work at the Paramount Pictures Studio lot on previsualisation for one of the final sequences.

Dan Kripac (lead 3D artist, Rising Sun Pictures): I was a new-comer to the freshly formed Sydney office and the counterpart to Ben who was leading the Adelaide 3d team. The Sydney team were charged with producing the water and various atmospheric FX surrounding and interacting with the shuttle as it crash landed. It was an exciting time for us building up our pipeline, getting to know the all the talented RSP team members and getting a synergy going to produce a fun adrenalin pumping opening sequence.

Tylney Taylor (3D artist, Rising Sun Pictures): I had literally just come fresh from Europe. Dan Kripac had made all of the water there – he was an absolute God with all the amazing shaders he had written. I’m a trained aerospace engineer and they asked me to do the particle and dynamics effects that would be layered under and over and around the space shuttle.

Ian Cope (visual effects producer, Rising Sun Pictures): The Core was a great ride – my first proper VFX project at RSP – filled with enthusiasm and trepidation. There were lots of challenges, including working across two locations, rolling out new infrastructure, such as our publishing file system, color workflows, and more, and building a studio from scratch in Sydney to go from 2 employees to approximately 30. One tricky thing was even understanding the American accent, and taking notes by writing things down phonetically before going and working out what the hell they meant.

Planning the landing

Greg McMurry: I had a whole previs done for the landing. It was originally planned that the space shuttle would land at LAX as an emergency landing. Then because of September 11, we couldn’t shoot at the airport. So we just came up with this idea of having them land in the Los Angeles River. We converted the previs to be for landing in the river.

Tony Clark: Greg told me about the space shuttle sequence and I thought, ‘Yeah, that sounds amazing!’ I had no idea of how complex it was, because at the time the company was really just learning to do complexity. The general level of complexity out there wasn’t particularly high in the world and it was the domain of a really finite group of people at the time.

First, the re-entry

Tony Clark: We start with the shuttle in outer space, and the actual re-entry scene was very challenging, partly because there’s limited reference available for what a spacecraft looks like entering the Earth’s atmosphere being surrounded by ionized air particles.

Greg McMurry: I had access to a consultant for the space shuttle to talk about how things looked. At one point, Rising Sun sent me a rough draft of the re-entry approach shots and it showed this big long plasma tail that came out from the shuttle as it was coming into the atmosphere. It looked great, but we really had no reference for what that was supposed to look like. I showed him what RSP had done and he says, ‘Well, from the little that we’ve seen, I think that’s pretty much what it looks like.’

Tony Clark: It was quite fascinating because some years later we had a similar effect in Gravity – still with no reference. You have to decide whether to err on the side of realism or err on the side of drama.

Ian Cope: It was a nice journey to go from The Core in 2003 and then to Gravity 10 years later, which ended up winning the VFX Oscar. Even greater was that the original team members who worked on the original were on Gravity. It shows how much the company has progressed, but that our commitment to amazing movie moments endures.

The live action elements

Greg McMurry: It was one of the very first times we were able to get a filming permit to get a helicopter in the air after 9/11. I asked the helicopter pilot, ‘Can we get a POV of the space shuttle coming down and going under a bridge? Can you fly on helicopter under one of those bridges?’ And he just said, ‘Sure. I’ve done it several times.’ The first time we did it, the helicopter looked like a pea – those bridges are actually massive.

Ian Cope: I recall once a re-shoot that was due to happen was delayed because they found a dead body in the LA River – it was my first taste of the random things that happen in the film industry.

Tony Clark: Greg is a guy who comes from a camera background. So he had a good sense of how to visualize the shooting of all that and what pieces would work when you brought them together.

Greg McMurry: We did some of the insert shots of the shuttle crashing into the bridge and side of the river practically. For that we actually started with a miniature that we had built for when it was going to land at LAX. We had Jack Sessums make some large scale pieces that we could smash. It really gave those parts of the sequence a tactile feel.

Making a space shuttle crash land

Tim Crosbie: The big CG asset work was looked after primarily by our Adelaide team which added a little to the complexity for sharing across offices but really allowed us to explore how best to work with remote teams and workflows – something that we had to be good at even back then. Rendering the Earth (and the shuttle) for some of the really long shots took out the farm for quite a while so we had to plan things very carefully and get them right as often as possible first time. No rendering on the cloud with what feels like infinite CPUs, we had to make this all work with what we had on site.

Tony Clark: There was no real physically-based rendering being used in a big way then, so any lighting that had to be done had to be explicit. When we were lighting for shadows or passing under bridges or anything like that, those objects all needed to exist and the bounce lights all needed to be created.

Greg McMurry: With that sequence, too, we were really going to have to deal with how the space shuttle crashes through the water in the LA River. In those days, there weren’t a lot of studios doing water. ILM had done The Perfect Storm and I remember VFX people after that were saying, well, we can do water now! Tony at RSP said, ‘We can do it, we can do it.’ And I think they did a great job with that water.

Tylney Taylor: The particle effects were done in Maya. Back then there was no software rendering of the particles. They were all hardware rendered sprites. With RSP system administrator Joe Connellan, we set up some of the render machines to go through the hardware renders when people weren’t using them.

This was all straight particles. I programmed a particle spline field. You had a curve and I made the particles run along the curve and then around it. You could control essentially where you wanted certain vortices to pull the spray around. 3D artist Jeremy Pronk helped me build a plugin for that.

*That* scaffolding shot

Greg McMurry: We went out to the LA River with the intention of getting a greenscreen up. But when we got there to shoot, we realized very quickly that there was a pretty stiff breeze which meant no way were we ever going to put up this giant greenscreen. Ultimately I told Rising Sun, ‘Um, sorry, there’s no greenscreen for that shot.’ But I said that I would pick a take right away and give them the entire post-production period to roto that shot. We all knew it was going to be a difficult task.

Tim Crosbie: Camera tracking and other tools that we take for granted today would have made the whole process a lot easier, but back then it was pretty much a case of roll up the sleeves, dive in and get on with it.

Ian Cope: That was the infamous shot number ‘co_349C’. It will never leave my brain thanks to its length and brutal rotoscoping of a multi-level scaffolding over 800 odd frames.

Tylney Taylor: That scaffolding was six people roto’ing for six months. They were amazing.

Tony Clark: It was brutal, but, you know, they paid us for it. And everybody understood the value of it. It adds to the believability of the moment. There’s a whole thing about letting cameras be free and letting things get dirty and between the camera and the CG – they’re the things that you need to do to make shots believable.

Greg McMurry: RSP delivered me roughs over the period so we could screen the shot. They worked on all the nuances required, roto’ing all those bars and everything from the first day we started on post right to the end.

Tylney Taylor: We had problems in stabilizing the shot. Tim Crosbie and I worked on it. I tracked the shot as well as we possibly could get it, with that scaffolding running in the foreground in 3D Equalizer. Then Tim stabilized it further. We were close to giving up and then we spent some more time on it, and we got it.

Tony Clark: The poor people who rotoscoped every frame of that have gone on to have incredible careers out there in the world, subsequently.

A film (!) workflow

Tim Crosbie: This was all still in the days of film. Digital intermediate technology was in its infancy and our CG work had to integrate seamlessly with the color profile of the film stock that was used, not just what was shot and scanned but also how the images were printed.

Tony Clark: You had to make your work fit into the film plate, and integrating computer graphics with film plates was tricky because of the tonal response and the color response of film.

Tim Crosbie: There was quite a bit of maths and maybe just a little bit of educated guesstimates involved there. I remember being hunched over a calibrated lightbox looking through a loupe at printed dailies being a common occurrence as we got close to finalling our shots.

Greg McMurry: In terms of getting plates to RSP, we used to have to mail our drive – we would just put everything on a hard drive and FedEx it to Australia.

Tony Clark: When the work was ready to show them, the way that it had been done at the time of Red Planet was that we would send back a Betacam SP tape in NTSC. But then we started adopting Quicktimes where we would send them a link and they would download the Quicktime.

Instead of it being this two week turnaround where it would take you a week to write the tape and pop it in a bag and send it and then look at it, we turned it into this overnight turnaround. When we had a call with them, it would still kind of be blind and we’d all have to describe where on the Quicktime frame there were any issues.

But we started to get into this rhythm with our clients where they were saying that us being half a world away and seven or eight hours behind them was actually an advantage. They’d look at our work in the morning that they downloaded from the STP that would be able to put it into their cut and then they would be able to have a call with us in the afternoon.

You can probably see there was actually a pattern of interactions that happened between us and the end user where we were all wishing that we were looking at the same screen together. And that idea was the beginnings of where cineSync came from, based on experiences on Red Planet and The Core.

Greg McMurry: Sometimes I say to Tony Clark that I’m sort of responsible for you guys thinking of writing cineSync…

Science-fiction fun

Greg McMurry: With The Core, we weren’t trying to make any great science-fiction reality. It was just a ride, you know?

Tim Crosbie: The whole movie is a nice tongue in cheek disaster/comedy romp that doesn’t take itself too seriously. I’m really proud of the results that our team produced. It’s still a stand-out VFX sequence that holds the test of time. I’m very tempted to take another look, it’s been a while.

Ian Cope: And the sequence almost never made it to the movie. When the space shuttle Columbia, on Mission STS-107, broke up on Feb. 1, 2003, there was a call to remove the sequence. In the end it was left in there as a tribute to the bravery of the astronauts who had lost their lives.

Tony Clark: We had come from doing some fairly small scale, but good-looking computer graphics; I don’t think we’d ever done a show that had such a large amount of integrated computer graphics and simulations with environments. So we were just learning everything – altogether – all the time on the space shuttle landing.

Ian Cope: Working with Greg McMurry was great, and we still work with him to this day. As an aside, back then Greg had a train set that you could view and control from the internet – pretty cool for 2002…

This is a brilliant oral history! Thanks for publishing it!