Later this week, a new animated version of The Addams Family will be hitting cinemas, care of directors Conrad Vernon and Greg Tiernan, and Cinesite.

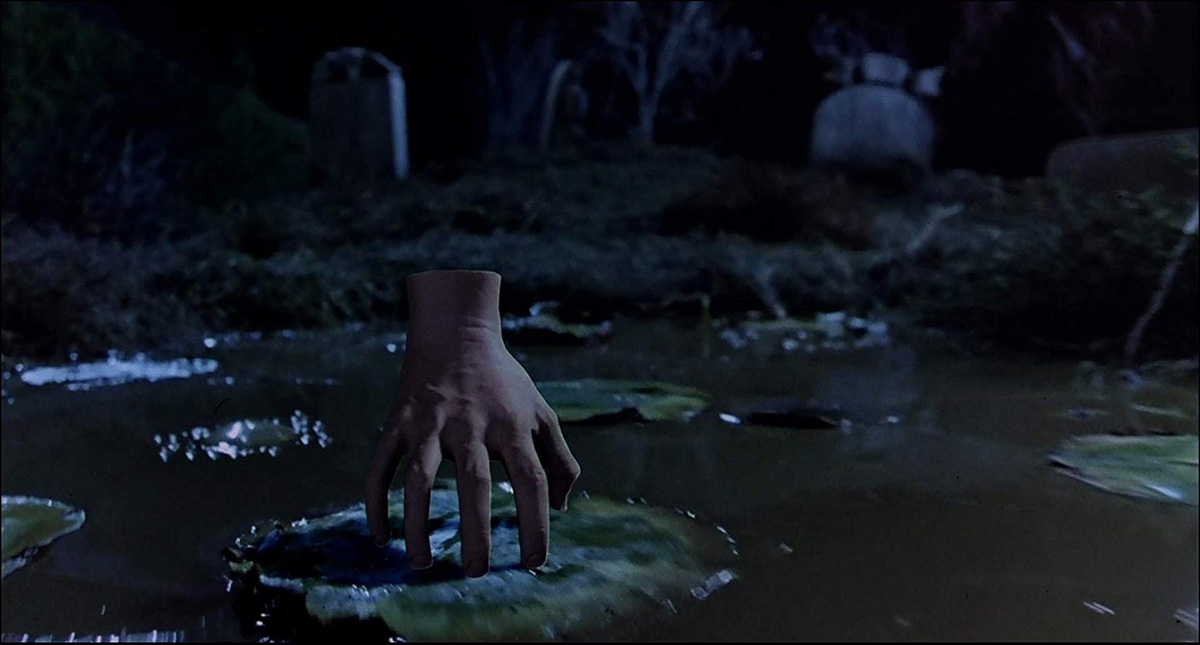

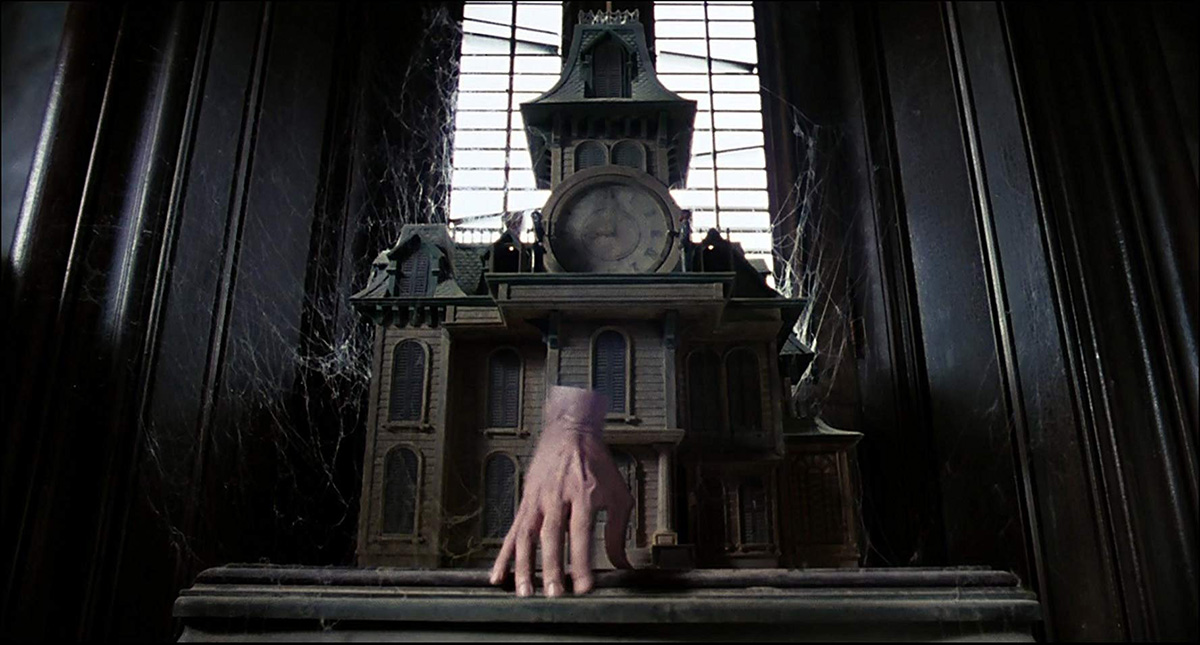

In honor of this release, befores & afters is going back to the early 1990s, when director Barry Sonnenfeld helmed two Addams Family films; the first was 1991’s The Addams Family. A major effects challenge for the movie was Thing, the disembodied hand. Since it had to crawl around, do stunts and generally ‘act’ in scenes, Thing was essentially a principal character.

These days, a ‘live-action’ Thing may well be carried out solely in CG, but back then it was only early days in that area. So, how would Thing be brought to the screen? I asked The Addams Family visual effects supervisor Alan Munro to run down the process for the 1991 film for befores & afters – the VFX supe scored the gig by suggesting to the filmmakers that a very well known dancer could serve as reference for the creature, and then later advocated for a real-life human to perform Thing.

Here’s Munro’s (hilarious) breakdown, which includes details of the actor hand casting process, the minimal use of prosthetics and the painstaking rotoscoping required.

Alan Munro: My association with The Addams Family began in Scott Rudin’s office in 1990 on a sunny summer Monday. Actually, I have no idea what day of the week it was. I mention this to remind the reader up front that what I’m writing isn’t truth, it’s the world viewed backwards through three decades of liquor-stained cellophane. Where was I? Ah yes, sitting in the sunshine on Scott Rudin’s brown leather couch with Scott, and director Barry Sonnenfeld. I was there to audition for the job of visual effects supervisor. Naturally, Scott and Barry wanted to know how I would create Thing.

“I have no idea,” I answered, truthfully. “And right now, I don’t care. First, we need to decide who Thing is, and what he is doing. Once we know that, we’ll figure out how we’re going to make him come to life.”

“Okay,” they asked, taking my bait, “Who is Thing?”

“In the script, Thing has been conceived as a family pet. Not so much a faithful dog as a hapless hamster, who simply scurries about the house. To me, Thing needs to be much more. He needs to be magical. He needs to be Fred Astaire.”

“Fred Astaire?”

I continued: “Think about it. Fred’s characters aren’t magical per se — they are grounded in the natural world. At the same time, they don’t seem bound by natural law. Fred is so graceful, so elegant, so effortless, so unbound, when he dances up the wall and onto the ceiling, it seems like the most natural thing in the world. That’s the quality Thing needs to have. Natural, yet unnatural. Bounded, yet unbound.”

I got the job.

While I take some credit for who Thing was as a character, I cannot lay claim to how Thing looked. That honor belongs to production designer Richard MacDonald. And also to a children’s birthday party puppeteer.

To my mind, Thing’s look was quite obvious. in keeping with the Fred Astaire theme, Thing should wear a starched white french cuff fastened with an Addams’ Coat-of-Arms cufflink. What would Thing’s wrist look like? You’d never know. The inside of the cuff would be deep enough and fall off into shadow so you’d never see inside it. Simple, elegant, magical.

“Thing wearing a cuff is ridiculous,” scoffed designer MacD (the nickname Barry had bestowed on Herr MacDonald), “It’s like putting a hat on a hat.”

“No,” I corrected, “It’s like putting a cuff on a wrist. But never mind that. How do you think Thing should look?”

“The inside of his wrist should be like a teacup.”

“Huh?” I replied (By the way, all the dialogue herein is paraphrased with the exception of this one line. I’m positive that was my reply).

“When you look into an empty teacup, you cannot see the bottom.”

What MacD meant of course was that the smooth porcelain inside slope of a teacup creates a vague illusion of infinite depth. If you’re falling down drunk.

MacD continued: “As Thing will be a puppet, this will look most correct.”

“Correct or not, Thing will not be a puppet,” I interrupted. “Thing will be a real person’s hand, with the rest of the body optically removed.”

“No,” MacD insisted, “He will be a puppet. I’ve already found the puppeteer.”

“This I gotta see.”

The next day, there appeared in my office a very nice man in green-checkered slacks carrying an orange checkered carpet bag. The very nice man opened the very large carpet bag, pulled out a cassette player and placed it on my desk. Next, he lifted out two marionette control bars with a dozen strings each tied to an articulated wooden hand. For the next three minutes, the wooden hand waltzed to The Blue Danube on my low pile office carpet. The hand did in fact have a hollowed-out teacup wrist — although this had been done to hide some of the string connections. When the waltz finished, the very nice man asked in his very thick Czech accent if I wanted perhaps to see a goat dance the polka. I politely declined. Before he left, the very nice man made me a very nice balloon dachshund.

Happily I had invited everyone — including Barry the director and Scott the producer — to watch the proceedings with me.

The verdict: Thing would have a teacup wrist, and MacD would have no say in how any effect would be done.

Sometimes you lose the battle but win the war.

Next came casting. My first choice to play Thing was a friend, Don McLeod. Don was a brilliant mime, an apprentice to Marcel Marceau. His main claim to fame, however, was as the “American Tourister Gorilla” (for those old enough to remember, it’s the commercial where a gorilla, played by Don, would try to bust open a suitcase). The first camera tests of Thing were shot with Don. Amazing as his performance was, Don’s stubby hand simply didn’t look the part. Fred Astaire’s moves without Fred Astaire’s lithe form ain’t Fred Astaire. Exit Don.

I made a list of potential alternates. Other than mimes, the obvious choice was magicians. What better than men who’d trained to perform complex hand movements. The casting call went out to two dozen sleight-of-hand artists. What a day when all two dozen answered. Never have I been asked for so many quarters, divined so many playing cards, or had so many eggs pulled out of my ear. In the end, there was only one choice.

Christopher Hart had been an assistant to David Copperfield (he greatly resembled David which had been used for several of David’s most famous illusions). Aside from being a skilled magician in his own right, Chris was tall, smart, athletic, and had large beautiful hands. All that aside, Chris seemed vaguely normal — which doesn’t sound like a high bar unless you’ve spent an afternoon with two dozen magicians.

We had our Thing, but how to achieve the effect? Seems simple now, but back then — before the computer era — everything had to be done either practically or using an optical printer.

I turned to my friend and long time collaborator Pete Kuran. Together, we decided to shoot all shots in two passes — with and without Chris. Chris would wear various prosthetic wrists. For front, top and profile shots, Chris would lie face-down on a car mechanic’s dolly, his arm outstretched, wearing a black sleeve. The false prosthetic wrist would be added, turned upwards, giving the illusion that his missing body was positioned above. For shots from behind (or when Thing had to turn around), Chris would be positioned above the camera, with a prosthetic placed around his actual wrist (to create an edge).

In post-production Chris’s body would be removed via rotoscoping — a painstaking frame-by-frame animation process. Being the originator of the Star Wars lightsaber effect, Pete was Hollywood’s undisputed master of rotoscoping. The second pass, which contained the background without Chris, would be used to replace the areas where Chris had been removed. The pieces would be sandwiched together using an optical printer. Simple concept. Devilishly tricky in practice.

These optical shots using a real hand would be intercut with shots of hand puppets. Not marionettes, but mechanical hands covered in lifelike latex, designed to perform specific tasks (Thing as a golf tee, for instance). For this work, I used my old Nightmare on Elm Street collaborator, Dave Miller.

In this way, we could keep the audience guessing, from shot to shot, exactly how the effect was being done.

The first day of production we shoved Chris under a table so Thing could play chess with Gomez. Everything needed to be rock steady to make our two camera pass technique work. Unfortunately the chess table wobbled. And wobbled. And wobbled some more. Stabilizing it took forever. The set became a tangle of guy-wires. Barry nearly had a nervous breakdown. After that fiasco, I had my own camera unit. Essentially, I directed every shot of Thing in the film. This is not to say Thing is any more my creation than Barry Sonnenfeld’s, or Chris Hart’s, or Chuck Comisky’s, or two dozen other people on the crew. It’s simply the way it was organized.

See Alan Munro’s VFX credits at IMDB.

Very cool! Thanks for getting the interview 🙂