Featuring several of those classic Laika breakdowns.

When you think of stop-motion animated films, you think of artists meticulously hand-animating a puppet, snapping a frame, and doing that for hours or even days for a shot that might only last seconds on screen. But with films from Laika, that can often be just the start of the process of bringing a shot to life. This is because the studio also makes significant use of visual effects in the form of CG characters, set extensions and clean-up work in creating the final frames.

Getting a character on screen for a Laika film, such as for their latest release, Missing Link, might even be equated with making a live action film, where the ‘plate’ is just the beginning, and visual effects helps bring everything together.

The role of VFX and CG

“My philosophy is that I want to put the best possible version of the image on the screen,” Missing Link director Chris Butler told befores & afters. “It’s not about hiding the stop-motion, it’s not about polishing the stop-motion so much so that it becomes something else. I think it’s about taking what’s so fantastic about stop-motion, but not allowing that to limit your storytelling. We will do any trick in the book in order to give the audience the best possible version of that frame on the screen. And I think what it’s allowed us as a studio that does stop-motion to tell bigger stories, to have a wider canvas on which to play.”

The stats certainly tell the story in the role visual effects came to play in making Missing Link. There are 1486 shots in the film; CG set extensions were required in 465 shots, 460 had CG elements, 325 involved CG animation and 446 involved 2D and puppet seams clean-up. There were 531 CG assets built and 182 CG characters created.

Laika Studios / Annapurna Pictures.

“With our VFX department, the lines between the digital effects and the practical effects are becoming increasingly blurred,” says Butler. “I’ve worked with our visual effects supervisor Steve Emerson closer than I ever have before, because they had to be involved in the project right from day one. I think that’s another reason why it is a great hybrid process here, because we don’t bring them in half-way through production. They are, right from day one, in those initial discussions. I think, without that, you would feel where one medium ends and one picks up.”

Emerson notes, in fact, that his department tends to touch “every single frame of these movies, even if it’s in-camera and we’re just doing spot clean-up,” while also taking things a lot further with CG characters and environments. Luckily, he says, they have the advantage of time.

“These films, they take upwards of two years once we start production,” notes Emerson. “We get to run in parallel with the other departments in pre-production if they’re developing characters and set, environments. And beyond that, once we actually get into animation, as soon as plates start to drop, we’re grabbing them and we’re starting to build shots. So it’s not the typical plate to shot. From day one, as soon as they start animating, it’s headed over to our visual effects department.”

This process begins with any puppets that are designed in CG for the purposes of 3D printing. “We’ll make sure somebody’s represented there so we can make sure that we’re all on the same page,” says Laika CG look development lead Eric Wachtman. “We’re making CG puppets that have to stand right alongside the practical ones, for example, in the Optimates Club, where there’s a bunch of layers of digital characters wedged in between two or three practical characters, to a level that we haven’t quite done before.”

Across the ice bridge

One of the major CG/VFX sequences in Missing Link sees the characters attempt to cross an ice bridge that begins to fall apart. The scene started with a practical build of 64 individually rigged ice blocks that could be independently controlled. These were made of layers of poured resin, with snow material packed on top. A matching version was created in CG that would ultimately be made up of 37,000 parts. “It had to match pretty tight,” notes Wachtman, “because it would cut from shot to shot between the digital and the practical.”

At one point, Mr. Link is seen clinging to a giant icicle that begins to crack. This was crafted in plastic resin and in silicone. To enhance the amount of reflection and refraction – and the cracking – the visual effects got involved in the final shots. “First there was a faceted hero icicle that was made out of plastic resin,” explains Emerson, “and that became the foundation for the icicle look. The animators animated with the puppet on the plastic resin icicle. And then we built a special registration rig, where that resin icicle could be swapped out with a silicone version of that icicle that we would crack, which was shot to acquire multiple lighting exposures. When you chop into silicone, you get these really interesting believable crack patterns.”

Finding Loch Ness

Another significant CG/VFX sequence in Missing Link is the opening encounter with the Loch Ness monster. The filmmakers first considered the animatics for that sequence, and, says Emerson, quickly acknowledged that visual effects would take care of the water component of those shots. “The plan was that we were going to be photographing the rowboat and animating them on greenscreen, and that we’d also be animating with a practical ‘Nessie’ puppet, with maquettes to inform the landscape surrounding the loch, and digital sky done in conjunction with the art department.”

Things changed slightly when the Nessie puppet proved more challenging than first thought to realize in the desired poses. The character was therefore achieved digitally. “That allowed us to be able to hit all the shapes that Chris Butler had wanted,” says Emerson. “It made things much easier on us for water interaction as well. Luckily we had the puppet out there for pretty awesome reference.”

But visual effects was also involved in an even greater way in the Loch Ness sequence, early on in the process. The rowboat, for example, was computer controlled based on an effects simulation of the water done upfront. Then, of course, visual effects were used for the water itself, including underwater scenes. “We did a lot of work with particulates and just mucking things up down there,” observes Wachtman. “We used a two-and-half-D system in NUKE to generate all the particulates for underneath the surface of the water.”

The work you might not see

Loch Ness and the ice bridge are perhaps sequences where the visual effects intervention is more apparent. But there is plenty of other work in Missing Link where VFX had a hand, and much of that is invisible. Some of the subtle work, for instance, was in making Mr. Link’s fur ‘flow’ in windy conditions. The puppet was made of relatively hard fur ‘scales’ made out of silicone, but to let it blow in the wind, the fur was actually painted with UV paint – not visible to the main cameras but apparent under ultraviolet light – that could then let the fur be isolated for augmentation by compositors. “We were able to take one of the color channels, which would give us a white value that was opaque at the tip and partially transparent at the base, and then we used that light value to drive distortion using NUKE,” says Emerson.

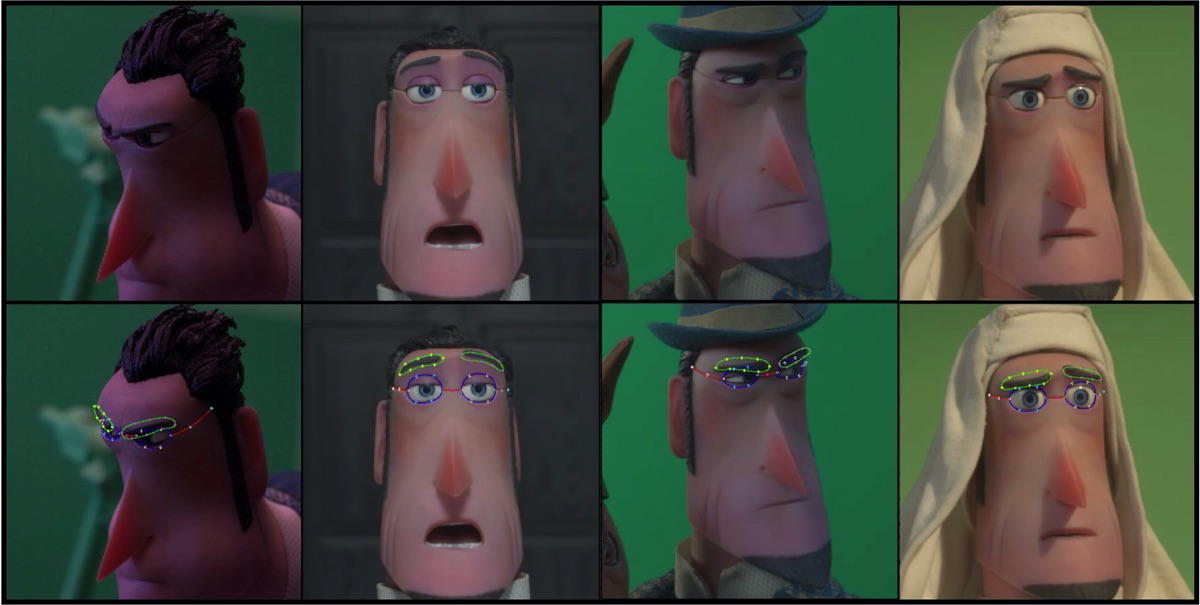

Other invisible work involved painting out rigs attached to the puppets, including remote ‘backpacks’ that allowed for small movements by the animators. The VFX shots even strayed into what could be regarded as ‘cosmetic’ work, says Emerson, such as the horizontal split line seams on faces that appear due to the replacement animation process or differences between the 3D printed puppets. “We also go through and we paint out just a little gap between the face mask that snaps on the puppet and the eyelids that the animator’s animating,” mentions Emerson. “We blend that in to just give it, the puppet, a little bit more of a human-like quality. All of that is handled by our roto-painting. In total on this film, they did cosmetic work on over 106,000 rapid protoype printed faces.”

Puppets and VFX, together

Clearly visual effects has opened up the story possibilities for Laika, which is not limited to action just on puppet-sized sets. “We don’t have those limitations now, and with every one of these movies we keep pushing and pushing those boundaries to see what we can do,” suggests Butler. “On ParaNorman, I remember sitting in an audience Q&A screening and talking about the character of Angry Aggie at the end, she was a combination of a practical puppet with a CG dress and a set of rapid prototype printed faces with hair that was spiking out of her like electricity based on melted glue sculptures. So it was a genuine hybrid, and I remember sitting with people who couldn’t work out what it was. They didn’t know whether it was CG, they didn’t know whether it was stop-motion, and I loved that.”

“I love surprising people and showing them something that maybe they haven’t seen before and they can’t quite work out how it’s done. That, to me, is great. There is something charming about seeing how something is made, but there’s also something really spellbinding about not knowing how it’s done, about it being a little bit of a cinema magic.”

Amazing what all the artists at Laika are able to accomplish. Beautiful work!

Too much CGI….Sad.

I mean to take nothing away from this wonderful film and the artistry involved, but…

In seeing it for the first time, and as a fan of old-school stop-action, I knit my brow. It was my impression that the film was almost entirely CGI. I get in a technical sense that there is still a significant element of stop-action. But sadly from an aesthetic point of view, it gets lost and I would say devalued by the wash of CG. I kinda wonder why bother since to even a savvy viewer the puppetry is glossed over.

Fun movie, good production, but only vaguely stop-action.