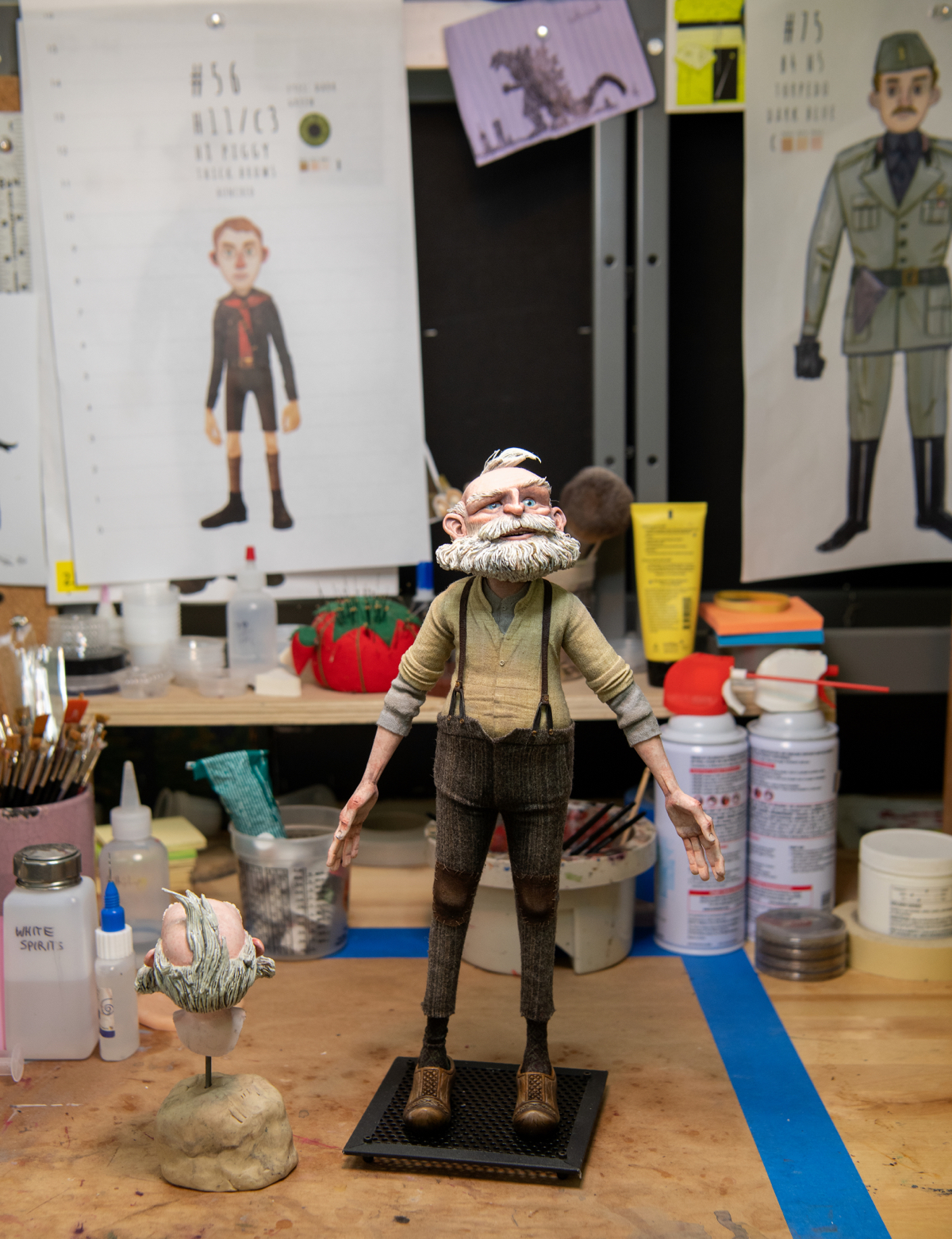

We break down how the puppets were built for the stop-motion feature.

This week at befores & afters, we’re jumping headfirst into Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio, with several features looking at the making of the film, from puppet builds, to animation, to cinematography and visual effects.

First up is puppet fabrication, and in particular the approach to puppet heads, which of course involves how the characters speak. In recent times, many stop-motion puppet heads have been brought to life via rapid prototyping and 3D printing hundreds of heads with poses and mouth shapes that are then used for replacement animation.

Indeed, this 3D printing process was how the Pinocchio character itself was made, largely because of the rigidness and wood grain look required. But for other characters, del Toro sought a more flexible performance, and that meant many puppets would incorporate mechanical components under a silicone skin that, when moved frame by frame, provide facial movement and lip sync.

befores & afters learnt more about the 3D printing and mechanical head approach, as well as the crafting of puppet bodies, from Georgina Hayns, a director of character fabrication on the film. We interviewed her at the VIEW Conference in Turin.

b&a: I wanted to ask you first about the decision to go with mostly ‘mechanical’ heads for the characters, but also the decision to do head replacement for Pinocchio himself.

Georgina Hayns: It’s interesting because Guillermo wanted it to be mechanical head animation, really, because he directed this film in a completely different way to how all stop-motion had been directed up until this point. He directed the animators as if they were live actors, not as if they were animators.

b&a: Interesting.

Georgina Hayns: He wanted the performance to come through in the puppets as actors rather than puppets. And what he felt was that mechanical heads gave more ability for the animators to actually act. They’ve got more control over the mechanical heads. When you’ve got a box of replacements, then that’s your facial acting just taken out of the equation.

So that’s why he chose mechanical faces over printed or replacement faces. But then when we did a test for Pinocchio with a mechanical face, there was an Uncanny Valley look to it, where we started to see the wood looking like rubber. So that’s when we all got together and said, ‘Well, I think it’s going to be better to do a replacement face.’

At that point as well, we could have gone about it sculpting the replacements, but the 3D printing technology just speeds up the process so much more. We were just very careful that it was on style with the mechanical heads as well, and on style with the boy of Pinocchio.

b&a: Let’s talk about the evolution of the puppets themselves. This starts–after designs–with clay maquettes, right? How does this part of the process work?

Georgina Hayns: The first thing we ever do with the maquette, once the director has approved it, is it’s molded, because it is such an important working model that takes us through the movie. So we cast them in resin, and generally just gray scale paint them. But sometimes we will also put color onto them, just so we can start to see what the characters look like with flesh tones.

b&a: I’m interested, too, in that step from maquette to, ‘Okay, we’ve got to turn this into an animatable puppet’ for the mechanically operated puppets. How does that occur?

Georgina Hayns: It can be really hard to perceive the level of detail that goes into this step, especially head mechanics on puppets. A head of a puppet is generally no bigger than three inches in diameter, and we’re cramming tiny mechanisms into that skull that essentially are going to operate jaws, lip paddles—they’re emulating the muscular movement and the bone structure of a human skull, or a dog skull, depending on what you’re making.

It’s an intricate process, lots of tiny engineered parts, and it’s also very organic, because when you’re working on head mechanics especially, you can’t overly engineer that, because a face is so asymmetrical. Nothing is a lump of engineered steel with symmetry in it. So we’re literally hand positioning each joint and pivot point into the head skull, depending on what the surface sculpt is. So it’s really interesting, you have to have an understanding of anatomy and the human body, and then you also have to have an understanding of engineering and mathematics pivot points and angles.

b&a: Moving on to Pinocchio specifically, for his body, I understand that was a 3D metal printed armature. Tell me about that process.

Georgina Hayns: We had an amazing artist, Richard Pickersgill, he’s one of the head puppet makers at Mackinnon & Saunders. And he had actually come out and worked on Coraline with me, for the latter part of the production. So when he was on Coraline, he worked with the 3D printing that we were doing on that. And then he went back to Manchester and introduced 3D printing to Mackinnon & Saunders. And he had been working back in Mackinnon’s for at least 15 years when Pinocchio came up.

We knew Pinocchio was going to be a challenge because of the scale of the puppet, and if we were going to try and make his parts in resin and do a lot of cast parts over metal, it’s always just a lot more fragile. And we knew that we’d got to have a very strong puppet. So Richard also had been doing a lot of research in England with the different 3D printing facilities, and he had found a metal printer that he was blown away with, in terms of the quality level of the metal printing.

We talked about it, we said, ‘Let’s do some tests.’ He and Peter Saunders set up that process. Richard built the Pinocchio puppet and he oversaw the computer modelers. So what’s great with Richard is he’s a brilliant practical stop-motion puppet maker. He knows how to make armatures, he can sculpt, he can pretty much turn his hand to it all. But now he also a really good understanding of the digital aspect of making puppets. He was the right fusion between the old and the new.

b&a: Right. Because in fact, that’s what Pinocchio’s body was as well, the 3D printed metal but with handcrafted parts?

Georgina Hayns: Exactly. In terms of handcrafted parts, he had silicone gaskets so his arms could move much more. He had a little silicone neck, and we did mold certain parts and casts. We did cast resin onto certain areas, but his whole body torso was 3D printed metal, and then all the joints were 3D printed metal as well.

b&a: So you’re 3D printing that, and you’re adding in handcrafted parts, and what’s the next step after that in making Pinocchio?

Georgina Hayns: The metal printed parts are attached to metal armature parts. The body torso is a 3D printed torso, but it does have some armature parts attached into it. And then the joints of all of the arms are 3D printed metal, but the rod that goes underneath and the outer surface is resin. The last part of it all is, when you’ve got all the parts made, you then have to paint them to look like wood, because everything’s metal or resin or silicone.

b&a: How is the armature arrived at? Does the animation supervisor or even director come in early and say, ‘I want my character to be able to do this’?

Georgina Hayns: Yes, we got a brief from the director and from Guillermo and from Mark Gustafson, the co-director, on what performance each character was going to do. We sit down in a round table meeting with all of our fabricators and the head of animation with the maquette in front of us, and we talk about what the expectations from the animation team are. At the end of the day, you have to make a puppet do more than anything a normal human puppet would do.

We’ll have certain points for the head of animation like, ‘Well, if we make it like this, it’s going to impede that.’ So there’s a lot of back and forth between us and animation. And then also our rigging team who are the external armature makers, they’re always there as well. Because, what we’ve found with animation over the last, I would say 15 years is, it’s become more and more rig heavy, because it allows for more extreme body performance. You can get a puppet leaping, singing, dancing, and just doing all this extreme movement, if you are holding it in space by something that’s really strong and really rigid. And also, a lot of our rigs can also be attached to motion control. So the rig is moving with the puppet.

b&a: Are the pieces of the armature off the shelf, or are they hand engineered?

Georgina Hayns: When we’re getting ready for a film, when you’re in a studio like Laika, it’s all in-house. But when you’re setting up for a film like Pinocchio where we were building the studio out, and actually buying everything to start making this movie, we found we work with two joint manufacturers. So there are people out there that just make ball and socket joints and hinge joints for a living. Mackinnon & Saunders had their person, and then we worked with Patrick Zung. He makes his own joints now as well.

What you do is you do a joint count, you’ll take the character lineup as best you know of what it is at the beginning. And you can work out pretty much, you can do a guesstimation of sizes and amount of joints you’re going to need. So that’s the first order of joints you put in to these people who are making them. And then throughout the movie you often find you have to put more joints, buy more joints.

They come as kit forms. But then we also design and have engineered certain key parts, like the miniature gears that operate the head mechanics. We had those made in England, Pete Saunders designed them, and then we bought a whole load of them for state side and Mackinnon’s used them on their side as well.

b&a: For the 3D printed heads and head replacement for Pinocchio, I’d love to work through the process here. You are relying on old school things approaches but also new school things like CG and the 3D printing. But where does it actually start?

Georgina Hayns: With Pinocchio it all started practically. So we initially did some drawn animation tests, and drawn cell tests over the puppet maquette head sculpt, just because it was really important with Pinocchio that we got the language of his mouth shapes correct. We had discussions, ‘Are we going to put lips, does he have lips? No, he doesn’t.’

It’s a cut piece of wood, and that’s how we should always style his mouth shapes. So those early sketches and those early drawn animation tests were all about figuring out the shapes and the styling of his mouth. Then we actually at one point did a claymation test, just to see how that would work in three dimensions. Because it was a quick and easy way that we could do it in three dimensions, without having to get things printed.

b&a: For that, is there an animator who you go to?

Georgina Hayns: Brian Leif Hansen, who’s head of animation, is an animator himself. He did a lot of those very early tests, because we had to budget everything out. We had to bring animators in if and when needed. So Brian did some of the early claymation tests, and then we had a couple of animators locally that we could call on who would come in and do some testing. We had one animator in England that would go to Mackinnon & Saunders and test their puppets. And then by the time we’d got a lot of our puppets coming through, we’d actually got two assistant animators already started.

b&a: How do things start getting modeled in the computer?

Georgina Hayns: Once the maquette is signed off by the director, then that maquette is scanned, and the face of the maquette was scanned and sent to the digital modeler, who then translated that into a digital model file. At the same time, we were still practically trying to figure out how we were going to separate the eyes and the mouth. Because in the past we’re all used to just putting a line across the center of the eye and separating the brows and face.

But a little wooden boy has got, number one, more challenges and his face isn’t really like a human face. So his eyes were holes, rather than any kind of ball or anything sticking out. And then we had to deal with the wood grain, and the wood grain on him is all vertical. So it would’ve been a nightmare to get rid of that line. I physically made a test head, cast a head out of resin from the maquette, ground the eyes out and made little car body filler, which we use a lot of.

It’s a resin paste that you can quickly try things out with. I did a practical eye test and I separated the plugs. When the maquette was first sculpted, the line around the knot of the eye shape didn’t link up. But I just linked it up, and at that point we went back to Guillermo, we showed him and said, ‘Look, we can make these eyes as a replacement entity, it doesn’t have to be a perfect circle, but the line has to join. Are you happy with that?’ And he said, ‘Happy, I love it.’

We developed that in Portland, while in England they were modeling the face from that scan of the maquette. And then from the model, once that was approved as a CG model, that goes to the rigger, the rigger can rig it, because at this point we’ve done our 2D tests, we’re on style with what we want the mouth to be. And then it can go into rigging that mouth and then animation.

b&a: And then how many face shapes do you produce out of that?

Georgina Hayns: One of the things that Guillermo was really nervous about with replacement facial technology, was the Uncanny Valley aspect of it. It’s almost, there’s too many faces, so everything’s so smooth that you forget its stop-motion animation. So we limited the amount of face shapes, and that really came out of Brian Hansen’s knowledge of stop-motion animation. And Kim Slate, who was the artist that was doing all the 2D breakdowns of mouth shapes. She also did the animation of the mouth. So once it was rigged, it went back to her and she was doing the face shapes. And it was really through early tests that we figured out how many face shapes we needed for our Pinocchio.

b&a: Then they’re sent off for 3D printing to an outsourced provider, is that right? What did you receive back?

Georgina Hayns: The faces were printed in color. There was a lot of back and forth at the beginning, and there were some nail biting moments of, ‘Is this ever going to work?’ Especially in the time that we had and for the budget that we had. But they got it, and I think it was probably about a three-month period of nail biting back and forth, and then a set of faces came back that were orangy brown, it’s like, ‘Oh, this is our guy!’

b&a: It comes back with a base color, is it then hand painted again?

Georgina Hayns: No, it’s printed with the entire color palette. We lay it all out and do it in a flat, and then that’s wrapped around.

b&a: So you do texture paint the 3D model, which gets 3D printed?

Georgina Hayns: Exactly. And the whole paint job is worked out. And what we did do for Pinocchio, which was really important, is that we got as close as we could and as happy with the faces, and then matched the paint job of the body to the faces. Because there was more ability for us to tweak our practical paint job than to do infinite tweaking with the facial technology.

b&a: How many bodies were made for Pinocchio?

Georgina Hayns: We had 32 puppets. We did print a couple of extra heads for stunt shots, but we pretty much had 32. And then masks we had in the thousands. The head itself is just a core, the back of the head. And then the masks are the face plates that go onto those.

b&a: In terms of the paint job for Pinocchio, it needed to match the 3D printed resin face. So what were the challenges there of doing the body paint?

Georgina Hayns: The biggest challenge when you’re using a 3D printed face next to a material that is opaque, like metal, is well, with the 3D printed material, light basically will shine through it. It’s a white plastic, the basis, but it’s semi translucent. So it almost weirdly gave you for free that translucency that computer animators are always trying to get with skin. So it’s a beautiful effect, but then when suddenly with the body, you can’t get that effect, because it’s not translucent, it’s made out of metal. You’re trying to match a color to a material that’s completely different.

Now, silicone works in a similar way to the 3D printed material. So the neck and things like that, depending on how much pigment you put into it, you can get a little bit of that diffusion of light through it. But with the body, we used the design of Pinocchio to our advantage, in that he’s a twig, a stick, and we started with everything at the top of his head being a lighter shade of the wood. And as it goes down to his extremities, it gets darker, like a natural tree does, like the branches of a tree. So it’s fresher wood around his face going into the sort of older bark, light wood around his ankles and things.

But then the funny thing is, when he walks from one light to another, Frank Passingham, the DOP, he loves gels on the lights. And you go from a blue light to a warm light, the light reacts differently with the paint and the translucency. So all hell would break loose on some shots, we’d be like, ‘Oh, my God, he looks like his face is green and his body is brown. What is going on?’ So if there was a whole shot that was a long shot, we would repaint the body just to integrate it. We could never repaint the faces because of the chatter, and there’s a consistency that has to be there.

b&a: How did mechanical head articulation work for different characters?

Georgina Hayns: We did mechanical head articulation for Geppetto. Geppetto was fully mechanical, and he had the ability to make all the mouth shapes needed, I would say, for 75% of the movie. He had three lip paddles in his lower lip. He had a hinge that those lip paddles were on, which would allow you to get an F, so the lower lip would go in to get the F. Then four paddles in his mustache, all of which could move backwards and forwards, but then sideways as well. So you could get a smile with his mustache.

He didn’t frown very well with his face. His sculpt was sculpted kind of as a sort of neutral frown anyway, because that was the character he needed to be. And you could turn him into a smile, but we did have an issue trying to get him to really grimace. So we made a stunt head, and the stunt head was never on the original agenda, we didn’t know we were going to need to make a stunt head. But when it came to it, the animator had taken the puppet on set, and he came back after his rehearsal and said, ‘I can’t get any of the shapes I need to for this shot. He’s really got to have a down turned mouth.’

So when we knew that it would’ve ruined that whole sequence if we didn’t do something. I took that puppet personally and operated on it. And when I say operated, it was essentially getting rid of the lip paddles that it had in there, building out a wire which was strong enough to hold the mouth shape, and then cutting the skin. So, sculpting the skin but with scissors into a frown. And it’s amazing what you can do with silicone. You can actually sculpt with the wet silicone as it’s going off.

I resculpted the mouth into a neutral frown, but a down turned frown, and then there was a wire to pull it down further if needed. And it was interesting, because that head was only made for one shot and it was used for probably a whole sequence. So we got our money’s worth out of it. And then the rest of Geppetto, his eyes are balls that sit and float in a socket, but the blinks are also in that socket, and there’s a thin sheet of plastic between the blink and the eye, so that the blinks can move separately from the eyeball.

And then because of his beard, it was quite tricky for the joint to hold the jaw in place. So we put a gear which just sort of incrementally pushes the jaw open and closed. And actually beyond that, he doesn’t have any other sort of sophisticated mechanics. He has eyebrow movement, so he has eyebrow paddles, but he’s not the most sort of full of movement puppet, and yet he’s the most expressive puppet. And a lot of that is down to design, I would say the more deep creased the character is, the better the performance is going to be with mechanics.

b&a: What tends to happen with these puppets after production’s finished? I mean, these ones in particular.

Georgina Hayns: The joy of working on this film, from the onset, we knew that Guillermo is a big collector of film props. So we knew that our puppets were going to go to ‘the house’. And one thing that we learned at Laika over the years is, that they are very important assets. You keep the puppets, you store them well, they’re going to go on, in fact, we’re actually having a huge exhibition at MoMA as well.

b&a: Okay, so that leads into another question. When they’re being transported from London to Portland and vice versa, or to the roadshow, how scared are you? And also how do you transport them, is it eggshell, foam type thing?

Georgina Hayns: We use Pelican cases. They’re made for guns, so they’re going to be great for our puppets. They’re actually brilliant because they have foam inside them that is pre designed so you can pluck any shape out of the foam. So things sit in there snugly.

They still get damaged though, which is why a puppet maker is always following the puppets. If we’re sending them for an exhibition to MoMA, we have a team of puppet makers that are going to set those puppets up, because just in putting the puppets in the case and taking them out of the case, the slightest little thing can damage them. But that’s part of our job, we know how to fix them. We made them, so we do a lot of post film maintenance to keep them going.

b&a: And do you ever get scared when they go out on the crate?

Georgina Hayns: I get really scared when you check them in for airplane travel. You’re waiting at the other end and you’re watching the conveyor belt, and it’s like, ‘Is it, is that, oh, yay! Pinocchio made it!’