The World War II submarine film is relying on some bespoke real-time, virtual production, live compositing, A.I. and metadata tech, all worked out in early pre-planning.

We all tend to know the previs, production and post stages of a film production. And we all also know that with new virtual production approaches, these stages are merging, re-ordering and just simply changing around more and more.

An Italian feature film project called Comandante, directed by Edoardo de Angelis, epitomises the paradigm shift in virtual production right now. The film is the true story of a World War II submarine commander, necessitating the need to feature ships and subs at sea and, of course, the ocean.

Doing that for real, or with traditional VFX techniques, can be expensive. So producer Pierpaolo Verga set out to adopt some different approaches by bringing visual effects designer Kevin Tod Haug on board. Haug soon brought together his own collaborators in virtual production, lensing and VFX.

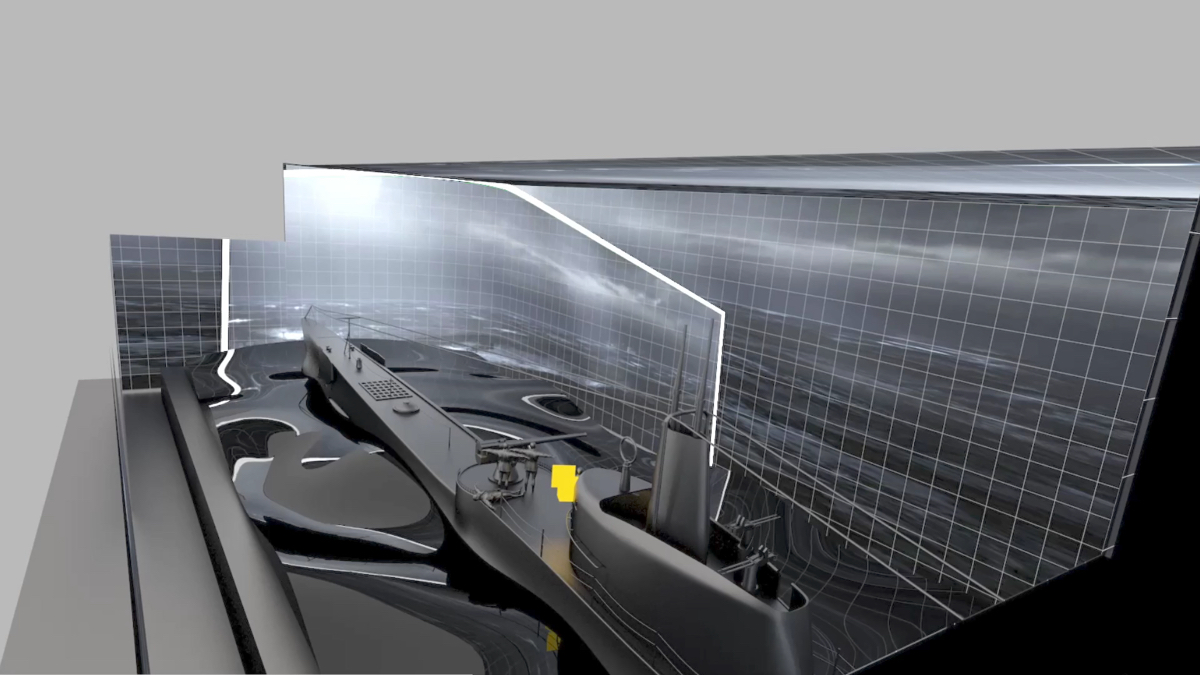

Indeed, Comandante–even before any live-action filming has taken place–has gone through a number of R&D phases, resulting in what Haug describes as a ‘near real-time’ workflow. The idea is that complex scenes (for example, actors needing to be placed on a submarine in the middle of the ocean, but actually filmed in a dry-dock) can be imagined and filmed, with new tools allowing the director and other filmmakers to get to close-to-final or final template shots almost in real-time.

The workflow has seen the collaboration of Foundry with its Unreal Reader software and A.I. CopyCat tool for interoperability with Unreal Engine and roto/live compositing, Cooke with its lens calibration and metadata solutions, in-camera VFX approaches from 80six, High Res and DP David Stump, and visual effects R&D and finals from Bottleship and EDI.

In this befores & afters round-table, we talk to producer Pierpaolo Verga, visual effects designer Kevin Tod Haug and Foundry head of research Dan Ring about the unique Comandante production.

b&a: Pierpaolo, how did this project start?

Pierpaolo Verga: Everything started about three years ago when we discovered the true story of this man called Salvatore Todaro, who was a commander of an Italian submarine during the second World War. We discovered that he was one of the few people in the world who, after sinking the enemies’ boat, would save the enemies that were drowning. That’s because, for the law of war, he was forced to sink the boat, but for the law of the sea, you have to save the men who are in danger. One of the submarines he commanded was the Cappellini.

This beautiful paradox made us fall in love with the story. One reason we were so moved by this story is because, at that time, but still today, there are thousands of people dying in the Mediterranean and the head of the Italian coast guard, during a press conference, told the story of Salvatore Todaro. We though at time that that story was so current, and nowadays even more.

After we had a script, we started talking about virtual production in general. We have funding to not only develop the script, but also the technology to make the movie as well. That’s where Kevin comes in.

Kevin Tod Haug: The idea that you developed the technology for the movie was a norm up until there became big visual effects vendors, which didn’t really happen until the late ’80s. So we had this paradigm of the production needing something and having to spend time to develop it and then do it.

Virtual reality was part of the discussion. There were certain characters that I knew and, as I was talking about how to do it, I reached out to them. Two important ones were David Stump, who’s Mr. Metadata for the ASC, an old friend of mine, and Peter Canning, who I had worked with on Nightflyers, where we did a certain amount of virtual reality stuff. And so I reached out to them and started poking around as to what existed in Europe and who might be able to do it and what is the state of the art.

It’s one of those things where the second you start to scratch off the paint, you start realizing how little there is underneath, that there’s an awful lot of shiny objects involved, but very few people have done it. There are no standards, there’s no best practice. It’s really crazy. One of the things that hadn’t really been touched at all really, was the use of metadata that was there already, just lying around. Everybody knew it was an issue, but nobody spent the time to make it work.

It’s an interesting gray area between what a vendor like Foundry could do, because it needed hardware vendors like ARRI and Cooke to join up. The only place where these companies meet each other is in production. They don’t actually have a natural connection that would come without us. And production is Production. You have to have a project or you don’t have development money.

Dave Stump introduced us to Cooke and the friends he knows at ARRI. Then I started talking to Peter Canning about it and he says, ‘Oh God, you need to talk to Dan Ring at Foundry.’

So the next thing I know, we have six people on the screen and we are all talking about it and putting it all together. Then suddenly there’s this €40,000 piece of glass flying across the world for us to play with because, from Cooke’s point of view, they built these beautiful lenses with all this great data in them that no one was touching. We set up some tests and did them at High Res, Peter Canning’s place, and brought it all together.

b&a: Dan, do you want to talk about Foundry’s overall involvement?

Dan Ring: Peter Canning got in touch after the RealTime Conference presentation we did back in 2020. It was about bridging the gap between on-set and post, or what we called our timeline of truth. He said, ‘We have a production. I need you to meet someone,’ and then he introduces us to Kevin.

The goal in one of our first tests was, could we use the lens metadata from Cooke? This is the problem that we’ve seen on the VFX side where VFX folks are saying, ‘Look, these lens grids are terrible. We can’t use them to get a good solve, we have to eyeball, we have to send it to Match Move.’ And then Cooke are saying, ‘Look, we have this. We made this. We made this ages ago, but nobody’s using it. How can we use it?” And Kevin was like, ‘This is where we’re going to use it. This will work here.’ And it did.

Then the next part was that we realized the marriage of on-set and post isn’t a technology problem. Well, it isn’t just a technology problem, it’s a production and a people problem. It’s, basically, what are you trying to solve? In this case, it wasn’t that the technology wasn’t about making just post lives easier, it was about showing the folks like Kevin, like Pierpaolo, like Edoardo, what’s going on, showing them a better version of what’s happening. Not even a better version, but informing them, giving them a better sense of this is how it’s going to look, this is how it’s going to work.

And, also forcing you to make decisions sooner as well. We know about virtual production having to load the virtual art department sooner, having more stuff happen on-set and then prep and pre-stages. But this is all completely brand new to us, this whole way of working.

b&a: You’ve all previously referred to this as ‘near real-time’ workflows. Kevin, what does that mean here?

Kevin Tod Haug: The thing about near real-time is that we went into this thinking, ‘Oh, we should be able to do this in real-time because the metadata is streaming in real-time.’ But as we got closer to actually doing it, we realized that the processors on both sides of the reality take a little time. There’s a tiny lag. That five to six frames tends to be the processing time to get it onto an LED wall.

But then there’s the problem of this movie, which is that we’re not doing hard bodies with easy texture maps and things that frankly, game engines do well. We’re doing chaos! Water, fire, wind. To be blunt about it, even if real-time gets better than anything we can do offline right now, there’ll be a better offline version that’s running parallel. It will never make sense to do real-time chaotic things, because you can always get a better product if you take a moment more.

We know that with a real-time approach, the director gets to see what he’s doing on-set in a way that makes sense, just like they would’ve been able to do before, but we want them to see a better version of it right away. It can happen soon, but it can’t happen as we do it. That’s where ‘near real-time’ came up. We also call it ‘near set’, where we’re not generating it on-set, we’re generating it in the cloud someplace. From a company in Bulgaria that’s using the cloud so that you can see it pretty quickly, but it’s not actually happening on-set. These are just terms that were useful as we go.

b&a: Pierpaolo, do you have an observation about this near real-time paradigm that you’ve been exposed to now and what you feel about how it can help shape this film?

Pierpaolo Verga: Well, I’d heard about the LED volumes when The Mandalorian was released. I had a few directors that were showing that to me and I was impressed by it, but it stayed in the little part in my mind. Then when we started talking to Kevin, we didn’t talk about this in the first stage, because the idea was to do everything practically, to build this submarine and to go out in the ocean and to shoot for real. Then reality came and we realized we couldn’t go out in the ocean for real. It was not legal. It was not safe. It was not possible. So we started talking about LED volumes and we’ve been working on that.

We did a few tests so I was able to understand this technology and I was able to share this project with the director. Edoardo was open to the idea of having something projected around the actors. It’s not the real experience, but it’s the closest thing we can get. So we decided that the word greenscreen was forbidden, and it is still forbidden. That started the process of working with Foundry and everyone on this virtual volumes technology project.

During the second test in London, something happened because Dan asked me what kind of things Edoardo would like to do. I knew Edoardo likes to shoot very long shots. Most of the time, it’s a Steadi-cam or a super long master for every shot. So I took the camera on my shoulder and I started doing some handheld camera moves and I was panning down around the character and, right after, what happened is that CopyCat just put that character on the submarine. We were in a studio, we had LEDs on the left, but on the right side we had lights and we had people. And on the floor, we had a normal floor. After CopyCat did its job, we had a character on the submarine. My pan was going down on the floor, on the deck of the submarine, with the water on the side and, right on my right, there was not anybody but there was the submarine and, on the left side, there was the ocean. So I said, ‘Why are we still using the LED walls?’

Kevin Tod Haug: This was the big paradigm shift. I started talking to Peter Canning again about this. Peter comes from lighting, and he starts saying, ‘Well, the whole point of LEDs here is not just interactive. If you put green out there, everything will get wet and it’ll reflect and you’ll be reflecting green and it’ll look like shit.’

Then there was this issue of the fact that, well, if you put nice LEDs–LEDs that don’t moiré–up on the wall, they’re going to get wet and they’re going to break. So then we’d use low-end LEDs and replace it all anyway. And then there was the issue of shooting daylight scenes. An LED wall can maybe give you better than a bunch of ARRI panels, but it can’t give you daylight better than daylight so maybe we should just do this in daylight and replace the background.

Things moved on to now talking about shooting out on the water, but with towns and modern artifacts in the background–certainly not in the middle of the Atlantic, but still doing everything else we talked about with the metadata, so that the director can look on the screen and see what he should see. It’s just, what’s in the background now, is good lighting.

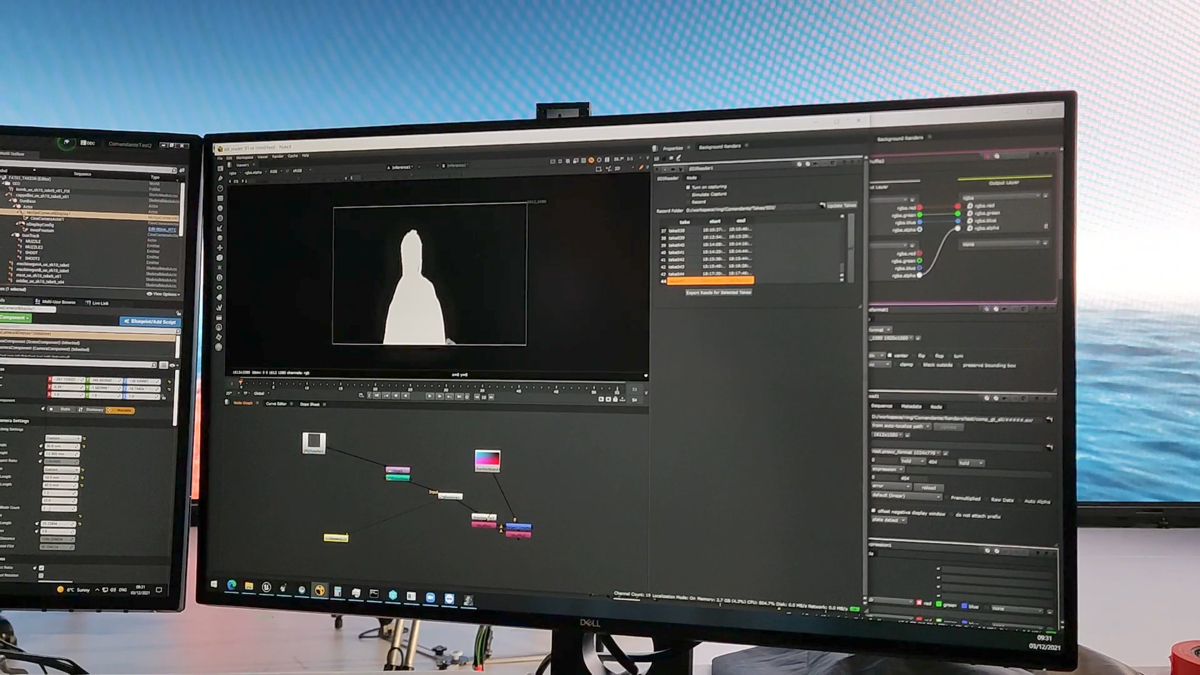

b&a: Dan, do you want to talk a bit more about that evolution of the Nuke workflow with CopyCat? You were using it here to basically rotoscope the actors off the background and be able to place them into a synthetic scene, right?

Dan Ring: Yes, just to go to something that Pierpaolo and Kevin had said, when I started asking Pierpaolo what does Edoardo want to see, Pierpaolo said, ‘Let me show you some shots.’ They are these really long Steadi-cam shots and it’s really clear that you’re never going to have enough LED wall to do these sorts of shots. They’re amazing. You want the director to be unencumbered by technology. Edoardo shouldn’t need to care about this. You should just shoot the way he wants to shoot. But what was really clear was that we were never going to solve this with LED walls.

I think ILM’s StageCraft has a nice thing of connecting two large volumes together to get these sorts of shots, but that’s practical for one or two shots. Edoardo wanted to do more than this. This is where this shift towards the next version of LED wall is no wall. Once we had solved the lens metadata issue with Cooke, the next thing was tracking.

For that we used the EZtrack system and once we had that solved, then we connected it. The workflow’s basically a connection of those bits for the hardware, and then Unreal for the rendering and then Nuke’s Unreal Reader and CopyCat. Unreal Reader is the tool for taking the renders, high-res’ing them, tying all the bells and whistles up, and then CopyCat for rotoscoping and getting the mattes that you want from the foreground actors, and then doing the replacement. And you need that for any AR application, to get the right segmentation.

The trick for that was to figure out the best way to use CopyCat. The original CopyCat workflow was, from the first test, we’d shoot all day and then I’d come home and get out my Wacom tablet and then roto till 4:00 in the morning, train until 11am o’clock, and then I’d download the model from the office.

The next stage was, we resurrected some tools from a previous project to help with the roto so I got to go to bed at 2:00am instead of 4:00am, but it was still the same process.

As we went on, we started doing more tests. We figured out a workflow for setting the wall to green or blue, doing some rehearsal takes with a locked-off camera, throwing it into IBK in Nuke, and then generating a model quite quickly. Like Pierpaolo said, the model you can generate from this is what you can get within 5-20 minutes. It won’t be the best thing, but it’s the starting point. And then it’s the same data set, so you can still have it running overnight, then you can kick it off, so that freed us up more. And it fits with Kevin’s paradigm of the near real-time workflow.

The idea is, you want to see a first pass of a very simple low-res version of something immediately. The director has to see that immediately. Then you’ve got the two-minute window. What can you do in two minutes? That’s where you do a little bit more. Depending on the length of a shot, you could probably throw CopyCat in there and do something. Then you need the 5-minute or 10-minute mark as like, if you had a compositor dialing things and noodling things in the background, during the next setup up then, what can you get there?

Then from there, it’s about packaging the assets and then being able to say, okay, we’re happy with this, we have the metadata that’s all saved in either Nuke or Unreal. And then we can package that off to the VFX vendor which is Bottleship who can then ‘overnight’ it and have it ready for dailies.

Kevin Tod Haug: Dan, I just want to jump in because you just said that word: dailies. Ultimately, you get a lot of this in visual effects where it’s like, ‘Oh yeah, that’s in post,’ and everybody’s just not that interested in the result. At some point or other they want to go old school, they want to do it all on-set. They want to see it. And basically the ultimate argument for this paradigm is that if you can see it in dailies, this is really old school.

This is all you could ever do in film. You didn’t get to see it right away in film. You had to wait until the next day and sit with your colleagues and look at what you’ve done and see how you did. It’s not, ‘Oh, it’s just on those post guys.’ It’s on the whole crew looking at it, going, ‘Oh, how could we do that better next time?’ Or, ‘How great was that?’ That dailies paradigm is a big part of this.

Dan Ring: Yes, exactly. We are going to be shooting on a 200 meter dry dock. Now, if you don’t get the shot you want and you find out three months later that you didn’t get it, that’s just not going to work. But for something now where we’re able to say, ‘Okay, well, can you pause, can you wait five minutes to see if that’s a thing?’ or ‘Edoardo, can point to the Unreal operator and say, Actually, can you move that explosion over to the left? or, Can we see what the framing was like? Can we save the take that we just did, or is there much work in that? Can that be fixed or do we need to reshoot?’

From a production sense, obviously, this makes Pierpaolo’s life very happy because we’re saving huge amounts of money. For Edoardo’s life, he’s happy because he can see the thing and he knows in his heart whether he’s got the thing. And obviously Kevin’s happy then because the post production budget is dramatically reduced.

Kevin Tod Haug: Also, I think actually what’s happened is the post-production budget doesn’t start at wrap of the last scene. Post-production starts in prep. We’re in pre-prep and Bottleship is doing R&D. You know, one of the hardest things to do is a boat’s wake. A boat’s wake is turbulence in two different dimensions with a barrier. I mean, it’s just the most complicated thing to do. We’ve all seen bad versions. On a submarine, you’re naked because it’s a convex thing. You can’t hide it like you can on a boat.

So the theory here is to get all of that R&D out of the way, seen by the director and approved before we actually start shooting, so we already know how dailies ought to look before we start generating dailies, which is not so different than how Doug Trumbull used to work on my favorite two old movies. I mean, honest to God, the tests that came out of Blade Runner look just like the movie, it’s just not Harrison Ford.

b&a: When you do start shooting, what is the planned methodology at this stage?

Kevin Tod Haug: We start with developing the assets. We use as many of those in previs as we can. We previs as much of the movie as makes sense so that we have a preview of what the dailies ought to look like.

After previs is prepping for the movie, getting it all ready, getting things pre-baked and ready to go. Then on-set, we have a version where the metadata’s coming in, tracking the camera properly, and we’re looking at an output of the game engine, Unreal in this case, and we see that on one screen, see the live on the screen and be able to mix the two together. Then, within the two-minute mark, we’re going to have what we’re calling a slap comp.

Then we have a temp comp. The temp comp is CopyCat. Not CopyCat’s best effort, but CopyCat’s quickest effort so we can see the two together in a clean way that’s decisionable. These are all big, ugly stunts and effects. You don’t want to make anybody do a difficult stunt more often than necessary, and not only because you don’t want to break them. So, you want to stop once you’ve got it, and special effects take a long time to reset and we need to know if we can move on. This is what that’s for. He can say, ‘Do I need to go to take three? Can I actually leave this setup? I’m ready to go.’ He can circle those takes and the 5, 10, 15-minute version will roll in shortly where it’s the best output of everything that’s happening on-set.

But at the same time, that’s gone up to the cloud and we’re already working on dailies for tomorrow so that the background is no longer the Unreal background. It’s now Houdini, something that had already been approved by the director, re-tracked and re-rendered as quickly as possible, in the most automatic possible way, that we can see in dailies. Then the director gives notes. I’m calling it a first take final. From that point on, we’re finaling those shots.

b&a: It’s almost like a template for the final shot.

Kevin Tod Haug: Right. Well, my best example comes from the art department. What do you see first? You see sketches. From the sketches you see maybe a foam core model. From a foam core model you end up with blueprints from which you can build a better foam core model. Then they start building the set and you walk around in the set and you go like, ‘Oh God, I’ll have to have that wall go away, etc.’ Then they start dressing it and painting it and literally two seconds before the camera rolls, someone’s in there fixing something in the background. Then it’s done, we hope. Of course, it also goes to Post where they can fix things, etc…

Dan Ring: Kevin’s way of thinking about this, even going back to previs, is this persistence of decision, making sure that whatever is decided in previs is moved through. And in Kevin’s mind, Kevin is just swapping out the elements. So you’re just swapping out the virtual, the render and previs frames, with something that’s actually a painted physical thing on-set or with a physical submarine. Or swapping out, what we’re calling them, “Gumbys”, with real people. Actors even.

It’s really nice then because then it’s very clear to everybody along the production what’s expected and what needs to be swapped out and what needs to be worked on and how it’s going to happen as well. So it makes previs even more valuable and important. Again, it’s great to see that and it was very clear then during our tests, when Kevin said literally, to ‘What are we doing?’ Kevin just pulls up the previs and says, ‘We’re doing this. This is what we’re swapping out today. This is what we need here. This is what the land should be doing,’ and it was immediately clear to everybody on-set. I think that’s a really nice shift in the way of work.

Kevin Tod Haug: I’ve done previs for a long time and one of the most horrible things is there was a lot of talk at one point about the digital divide, the fact that what you did on-set often got lost because you went into post and there was this divide. But there’s also been forever an analogue abyss where you created all this lovely stuff and then it just gets tossed because you have to go into production, which is all analogue, and then you come back out the other end. So that creative leakage has bothered me from the day we started doing it and one of the very first shows I worked on where we did extensive previs was Panic Room.

One of the things we did do on Panic Room was, when we liked a move well enough, given that director and his compulsiveness about wanting to see what he’s done, we would take the move out of previs and convert it into motion control files. The motion control would do exactly what we had done in previs. And so I’ve been looking at it ever since then as like, ‘Well, that’s the way it ought to go.’ You make that decision in the quiet moments in prep, when you can make those decisions. Then they’re just ready for you on the day. And, if you happen to decide you need a second or a third or the fourth camera that you didn’t plan on, well now you have time for it because “A”camera is ready to go.

b&a: I was going to ask you, Pierpaolo, because this process is different in some ways to the usual process, does that make it harder to budget and plan for?

Pierpaolo Verga: Well, this is an independent European production and we knew it from the start. Before talking to Kevin, I was budgeting the movie with vendors based on the screenplay. And numbers that were coming out of that were much higher than this. The technology is exciting for many reasons, but it is also useful because it’s saving us a lot of money and it has also been designed for Edoardo’s vision.

He will have many advantages because he’s going to be able to see almost in real-time what usually would take weeks. And on the other hand, maybe he will have to be a little bit patient because we will still have to have some technical rehearsals to train CopyCat.

Plus we are still going to be shooting on a boat on the sea. The dry dock is a brilliant solution for many shots, but there are some shots that are going to be done for real in the sea with a submarine built and pulled by another boat.

b&a: Where does USD fit into all this?

Dan Ring: It goes back to Kevin’s philosophy of making the final decision as much as possible in previs and persisting that. USD is entirely around that. The philosophy around that matches this exactly. In theory, you do want your virtual art department to build the assets. You want the previs team–in this case Habib Zargarpour at Unity–to bring the assets into Unity, make the decisions on timing, framing, animations of camera, lens decisions, and then say, ‘Okay, we have that. Now just import that into Unreal wholesale and then ideally just use that for your virtual production.’

For us as well, when we’re capturing the camera tracks, we bring them into Nuke in USD. Any edits in cameras then are persisted in camera, then we deliver them to Bottleship, who are working in Houdini, which is obviously very USD compatible. So the guts are there. This is the way it should work. Philosophically, USD is absolutely the way forward. It is perfect for this project. I’m really interested to see how far we can push this.

b&a: Dan, I also just want to ask about some of the things that Foundry has been working on for this film and learning about, and whether the plan is to feed those new workflows into Nuke CopyCat and Unreal Reader?

Dan Ring: Oh, absolutely. I mean, already a huge amount of work has fed back from Unreal Reader. Its feature set has dramatically increased and I think, in the next version of Nuke, you’ll see better stability, much easier to use and faster. CopyCat as well.

One of the main things is, when I’d be using CopyCat and it’s taking too long or hours to train, I’d be feeding that back to Ben Kent, who leads the A.I. research team at Foundry, saying, ‘Look, this just isn’t and going to work on-set. We’re so far away from reality here.’ And then he’d go away and say, ‘Let me think,’ and he comes back and says, ‘Okay, I made it faster. It now works in minutes rather than hours.’ Suddenly it’s in the realm of possible again.

The other main thing that we’ve been focusing on is the metadata capture. We still need that timeline of truth, that source of truth. At the moment, Unreal is the place where the data converges and we save it to a tape. My colleague, Niall Redmond, has built what we’re calling our VP assist tool, which is essentially a combo Unreal plugin and Nuke plugin that allows you to signal and trigger a take recording in Unreal and in Nuke.

So you’re capturing all of the metadata to take the sequence in Unreal, and also all the live footage off an SDI feed into Nuke. And then, when the take is finished, it renders through Unreal Reader with all of the AOVs that you need for your pass, brings the footage into Nuke, aligns the time codes, and then you’re in Nuke. That’s your comp. So in this world, where Bottleship has created those temp final comp templates, where we know the shot’s going to look like this, we know we’re going to need some color correction, we know we’re going to need to account for some things, we’re going to need to do some glows or shadows or highlights and things like that. We know what the comp is going to look like more or less in advance.

Now you just drop in your footage, you check it out, a comp’er can spend a minute tweaking things and noodling things around and then get that two-minute or five minutes to comp. The VP assist tool is the only one that doesn’t exist in the public domain yet, but we are planning on releasing that because that’s the last bit of icing. I mean, getting Unreal to be nice and collect all that data and in the right format and in the right way that could be brought into Nuke–I think that was the last piece of the puzzle, to make sure that all worked. But other than that, I’m sure that there’s going to be lots more additions to CopyCat and, I think, to Unreal Reader.

There are improvements coming to the UI as well. Another colleague who came from a live event background at Brompton, she gave it a nice description: ‘If you’re making anything that needs to be used on-set or live, your operator needs to be able to use this while having bottles thrown at their head because that’s the kind of pressure and environment that they’re going to be in.’ This is not how Foundry typically develops software. Most people don’t throw bottles at VFX artists, generally, but we are writing our software now to make sure that it’s possible. So CopyCat and Unreal Reader and the VP assist tool will be written with a guarantee that you should be able to use it while projectiles are fired at you…

Foundry is presenting a ‘Comandante’: Braving the Waves With Near Real-time Virtual Production Workflows’ talk at SIGGRAPH 2022 on Monday, August 8 at 9:40am.