The MR. X team breaks down their detailed creature work.

Diablos. Rathalos. Apceros. Palico. Nercylla. It sounds like a VFX dream to re-create these beasts from the Capcom Monster Hunter game series. And that’s exactly what the MR. X crew were tasked with doing for the live-action Paul W. S. Anderson film.

befores & afters talked to several of MR. X’s team—Jo Hughes (VFX producer), Trey Harrell (VFX supervisor), Ayo Burgess (DFX supervisor) and Tom Nagy (animation supervisor)—to find out how the studio pulled it off. Here they cover shooting plates without creatures, the creature builds, sand sims, digi-doubles and more.

b&a: With so many creatures and environments to create, what can you say about the workflow from concepts/design to VFX on this film? How did that process work?

Trey Harrell (VFX supervisor): Mr. X began developing concepts for Monster Hunter in 2014 alongside our long-time collaborator and friend, Paul W.S. Anderson. We produced a short during that period in which we worked out many of the issues regarding scale, physicality and how to shoot for creatures of this scale.

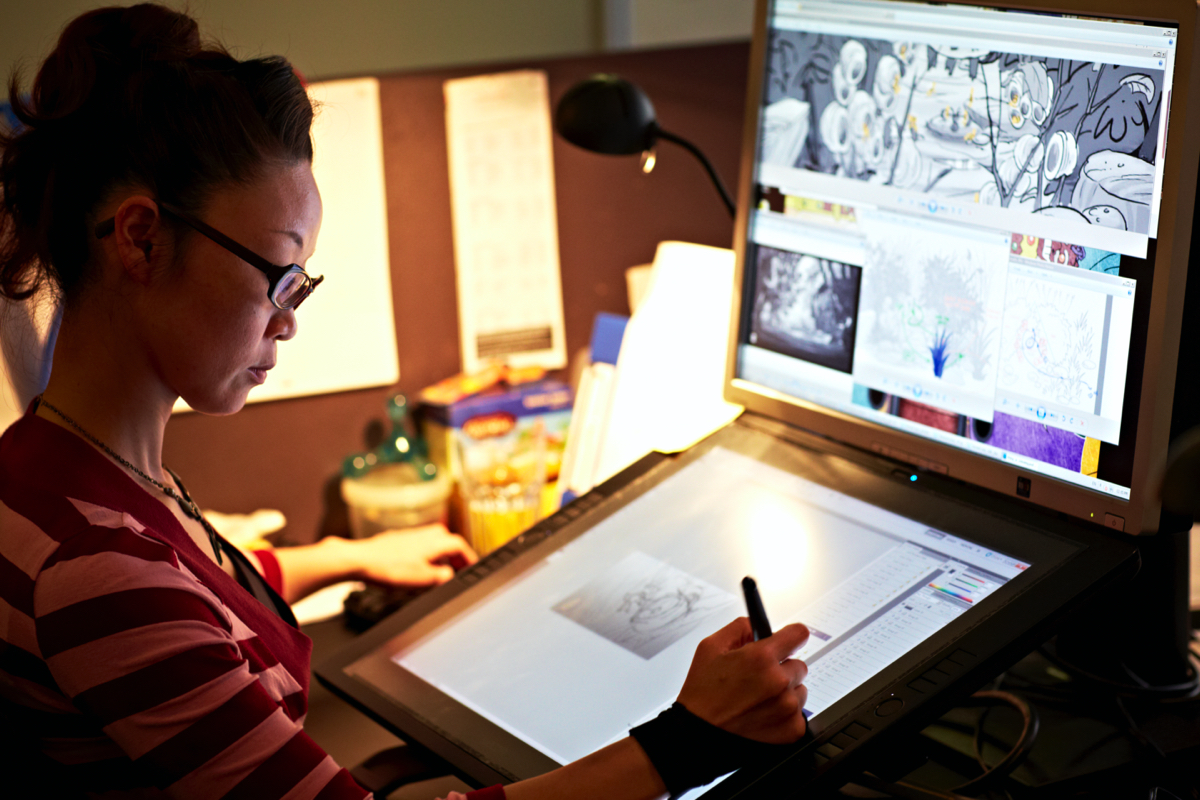

Ayo Burgess (DFX supervisor): With a project of this size concepts were essential to make sure that we executed the right VFX work inside of the schedule. Early concepts for the show were done here at MR. X to get the project greenlit. MR. X visual effects supervisor Dennis Berardi had a clear sense of what Paul wanted and usually would work directly with a concept artist to develop a design. All concept work started by referencing source material from Capcom’s Monster Hunter games, be it art book concept art or direct reference from one of the video games. From there we would develop the design to give it a real world interpretation. This usually meant realizing more detail than you’d typically see in a game by leaning on real world sources. For the creatures this usually meant interpreting more fine details, this was especially true for the Nerscylla monsters who had only appeared in much older games with low resolution assets.

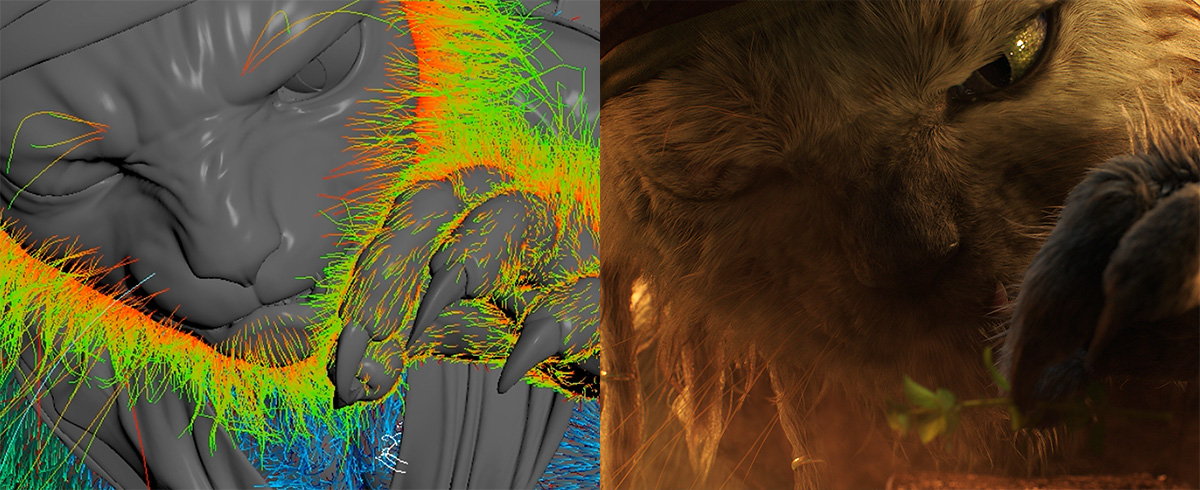

After concept art was approved by Paul, we would continue the design work in 3D. Utilizing tools like ZBrush to create 3D “clay sculpts” to further the designs and make sure they worked when making the jump from a 2D concept image to a full 3D model. This process allowed us to iterate creatively at a relatively low cost. By the time we completed this process for the various creatures, environments and effects in the show we had a good idea of what we needed to build for the VFX shots in the movie.

Building assets and planning shots is always easier with good concept reference and designs so in most cases we took the designs and fleshed them out in to full production assets without many surprises along the way.

To summarize, our general philosophy on the show was to always do a concept piece if there was any doubt about what something would look like to make sure we executed the correct VFX. We found this to be an efficient process that kept lots of space for creative iteration, kept cost under control and minimized the number of revisions we had to make to our assets and shots.

b&a: What kind of boarding/previs/animatics process was involved on Monster Hunter? Was this something that directly led into live-action production (ie with techvis), or was it used for more of a guide?

Trey Harrell (VFX supervisor): Many of the key concept frames were developed by our internal team, headed by Jordan Nieuwland, as well as the art department translated directly into the film almost verbatim as “big” moments. In addition, for some of the more complex sequences such as Artemis and the Hunter mounting the Diablos, MR. X generated techvis to give a sense of the range of motion and requirements for the practical “rodeo” rig.

b&a: In general terms, how did MR. X’s build team tackle the creature builds (ie. modeling, rigging, texturing etc). Any new approaches required here?

Jo Hughes (VFX producer): The Monster Hunter games have established these fantastic and beloved creatures. Our concern was to be faithful to the fanbase, but also to make a cinematic film that is photo-real. The film was shot in broad daylight so there really was nowhere to hide! We did our own research on real-world animals, to take inspiration for texture and shading, especially to add details to portray the immense scale of these beasts. Real-world reference was also imperative to make sure our digital creatures behaved in physically realistic ways. Two things we came back to time and time again were weight and scale; the surface details and the performance of these creatures had to work together to sell the photorealism.

Trey Harrell (VFX supervisor): For the Diablos and Rathalos, we had fairly high resolution ZBrush assets provided to us by Capcom as a starting point which we would use as a launchpad for the “cinematic” versions of the creatures. Our team would identify resolution requirements for each creature based on previs coverage, tactically targeting areas of the creature that would be most visible in shots. For these creatures, we took very few liberties with Capcom’s fundamental designs — it was important to us as well as Paul that the creatures matched what fans of the property were expecting to see. We would do exploratories on how the creature’s musculature and skeletal system would work, how the inside of Rathalos’s mouth would look, we added the ability for the Diablos to tuck its wings in for a more streamlined silhouette in motion and so on. We also developed facial rigs for these creatures as we wanted to give them substantially more dramatic range than “roaring” or “not roaring.”

For the secondary creatures and Gore Magala, we launched off from the most recent Capcom game assets. The Apceros and Cephalos, developed by Black Ginger in South Africa, deviated very little from the designs fans of the games might be familiar with.

The Nerscylla required more liberties taken as the older game designs for the creature were quite stylized from an earlier console era and didn’t fit into a more grounded cinematic world. The legs required another joint to achieve the range of motion necessary for some story beats and we gravitated a bit more closely to real world mantis and arachnid reference while keeping the iconic features such as the crystals on their backs. Mr. X worked closely with Capcom throughout production to ensure the base lore of the creatures were honored with any design modifications we might make. A fun piece of trivia: Nerscylla back crystals are the result of poison seepage from their bodies as they sleep inverted hanging from cave ceilings!

The Palico, Meowscular Chef, took a far different development pipeline. We worked with concept artist Guy Davis to develop early concepts of a version of the very stylized and cartoonish game character and transplant him into a more grounded reality. From there, our team did nearly a year of exploration on designs, grooms, animation mannerisms, facial performances and simulations to find the core of the character that ended up in the final film.

b&a: How were digital doubles crafted for the film? How do you work out how much ‘detail’ to build here—when do you know when to stop?

Jo Hughes (VFX producer): For all assets, MR. X used a system of three stages for asset development: Stage 1 was a preliminary build where we focused on silhouette, proportions, and a low-to-medium level of detail in textures – at this point, we would put them into shots to get performance notes, and “first-impression” look notes from the filmmakers. This workflow allowed us to get a greater number of assets into the majority of shots more quickly than if we had worked assets to higher level before deploying to shots, which garnered feedback across the entire film’s assets and understand not only the client feedback but also our own technical and creative notes, which allowed us to integrate all the feedback into a cohesive plan to make our Stage 2 asset. Only a few assets needed to be revised beyond Stage 2. This workflow meant we didn’t waste time “over engineering” with work we would never see in shots, and instead focused our resources on making our creatures and digital doubles perfect for their shots.

Trey Harrell (VFX supervisor): Our friends at Black Ginger supplied a full body photogrammetry rig along with key crew that we hauled to some of the most remote locations on Earth! Every single performer and stunt double in the film had full body scans made, and we performed FACS facial capture sessions for our key actors.

In general, we had a sense when production wrapped which characters would feature heavily and more hero (Artemis, The Hunter, The Admiral and The Handler) whereas we could safely assume the other digidoubles could be held to a midres standard.

As with any hero asset, the only time you know it’s safe to stop is when the film premieres. All of our key digidoubles were continually refined based on per-shot needs via our stage system until the end of production. My mantra is always “let’s see it in a shot” — you run the risk of overbuilding and missing the forest for the trees if you review endless turntables that don’t represent actual shots and actual shot lighting.

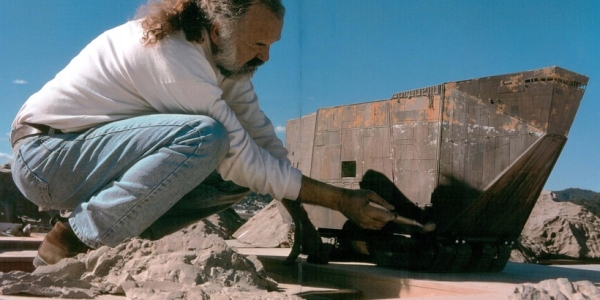

b&a: For filming live-action scenes that would have monsters in them, what were the things done on set for surveying, data, measurement, reference (including any stand-ins for monsters) and other things done when capturing plates?

Trey Harrell (VFX supervisor): We captured lidar and drone surveys for every single location in the film, leveraging DroneDeploy’s cloud-based terrain solves heavily. For all shots, we also captured chrome/gray balls under shot lighting at creature positions in addition to the usual HDR capture workflow. Paul’s a very organized and disciplined filmmaker. All of the key sequences were boarded shot by shot and we had a good idea for composition and scale based on that prep work.

Additionally we had a full-time monster stand-in on set as part of the VFX team, who would hold up eyeline targets for the actors. The scale of some of the creatures made this fairly challenging as there’s a limit to how big a stick one can hold up in 40 mile an hour wind! We would also occasionally utilize one of the drone team’s drones for eyeline. Low-tech solutions like measuring out cones to give sense of a creature’s scale from nose to tail for the DP and camera crew were also utilized, depending on the shot needs.

b&a: From a technical point of view, how did MR. X handle the sand simulations for the emergence of the Diablos? What other kinds of simulations were required when it interacts with people, vehicles etc?

Ayo Burgess (DFX supervisor): Sand simulations were one of our biggest technical challenges. All of our sand simulation work was done in Houdini using the Vellum Grains solver. Simulations were broken in to a number of layers:

Low res base – initial simulation to tune the overall performance of the sim. This would be reviewed and given early approval before moving to the next step

High res simulation – An enhancement of the base sim. This involved simulating many more grains of sand that were “guided” by the low res simulation

Dust simulation – A secondary simulation driven by the high res simulation. Fine dust was a key part of the look for the sand. Dust simulations were typically broken up even further in to a few different zones so that areas that didn’t interact could be simulated separately

Secondary grains – A final layer of added fine grains, e.g., in shots where the Diablos emerges from the ground you might notice grains of sand cascading from her body

Even with a really high level of detail in our sand simulation there was no way to feasibly simulate grains of sand at their actual scale (there are billions of grains of sand in a cubic meter).

To make sure that our sand grains never looked too big, we leaned on Houdini’s built-in renderer, Mantra, which contains a point replication procedural. This procedural allowed us to spawn millions of additional points at render time by replacing input simulation points with 100s or 1000s of smaller ones scattered around the source point. If tuned correctly this can have the effect of making the simulation look much more detailed and complex. This had to be tuned from shot to shot but gave us lots of flexibility to increasing the apparent detail of a sand element without going back to FX for a new simulation.

b&a: What kind of environment and foliage work was required for the Apceros creatures?

Trey Harrell (VFX supervisor): The team at Black Ginger, led by co-founder and VFX Supervisor Marco Raposo de Barbosa, spearheaded the Oasis sequence. Careful surveys were taken of the practical filming locations at Cape Town Film Studios and replicated in layout.

The Black Ginger team developed a custom destructible foliage pipeline specifically for this sequence in Houdini where ambient greenery could be laid out and arbitrarily made to tear, part or be trampled by the creatures whenever animation updates came down the pipe, as well as very hero shot-specific foliage assets that had to break or react a certain way.

b&a: How were Palico scenes realized? Can you talk about how any kind of stand in or stunt work was done, and any motion capture here? What were the fur simulation challenges for this character?

Trey Harrell (VFX supervisor): We felt very strongly going into production that it was important to have a performer be physically present to give the cast someone to interact with. Aaron Beelner was cast and performed the role in a gray tracking suit, giving Ron, Milla and Tony someone to play against. Our animators took a lot of guidance for timing and attitude from his performance as well, although our vision of the Chef had superhuman dexterity and speed, which no actor could match exactly.

In addition to the Steve McQueen reference that Tom leaned on, I’d always had in my head Toshiro Mifune in Yojimbo or Seven Samurai — in addition to effortless cool and swagger, he could shift from incredible physical humor and nonchalance to a primal ferocity in a heartbeat. As a card-carrying cat dad, I see this as probably the defining feature of feline behavior – those mood swings aren’t gradual at all and can be quite shocking.

In post-production, Meowscular Chef’s role grew and we performed motion capture sessions with our Palico lead, Andrew Grant, once we had the scenes blocked out, which were then retargeted and simulated on the Chef’s rig. Tom Nagy (animation supervisor): Several motion capture sessions were performed with our animation team, and given the complexity of this character we also used a wide range of video reference, including of Steve McQueen (he’s a cool cat after all), different martial artists, and of course real cats to sprinkle in some subtle feline mannerisms. This helped us to capture the nuances of his acting, and we fleshed this out further with keyframe animation to help accentuate and give him that extra pop on screen.

Ayo Burgess (DFX supervisor): We knew that Palico’s fur would be a big challenge from the beginning of the show. We did extensive concept work and organized reference shoot where we filmed real world cats in the studio to get a sense of how their fur responds as they move. We used Houdini to groom and simulate the Palico fur. We broke our groom in to “zones” to maximize control of the look and hand groom each section to match our reference. Our workflow was to groom a subset of curves called guide curves and then procedurally generate the final render curves. This allowed our grooming artists to maintain good interactivity in their process while still giving us the ability to generate millions of hairs at render time to match our reference.

We simulated our guide curves with Houdini’s Vellum solver and cached the results to disk. Then as a pre-lighting step we would generate the render curves and render them directly through PRMan. For fur shading we took advantage of the outstanding work that MPC did on The Lion King and used the fur shader that they made for that show. This is one of the big advantages of being under the Technicolor umbrella in that we can collaborate with MPC, The Mill and Mikros if they’ve solved similar problems recently. Luckily PRMan is the primary renderer for both MPC and MR. X so we they were able to share this technology easily. We initially struggled with the fur look using traditional hair shading models which are designed to match human hair rather than animal fur but found that switching to the fur shader from MPC solved those early problems and gave us a really nice look for the fur.

b&a: What very specific animation approaches were required for the Nercylla creatures—what reference worked and didn’t work for these?

Tom Nagy (animation supervisor): The Nerscylla were a unique challenge to animate, as they incorporate design elements of different insects, but are also enormous creatures and needed to move believably at that scale. We did use real world reference of mantises and arachnids to initially help define their movements, but everything needed to be adapted and slowed down quite a bit to make sure they were able to move dynamically, while still having the proper weight on screen.

Given that they only have four legs, we also used their front claws to not just attack, but help with locomotion and interaction with the environment in certain cases. For the hero shots, not having any recognizable facial expressions, we concentrated on strong, readable poses and silhouettes to imply their intent and thinking process. For the wider crowd shots, we didn’t want the Nerscylla to be a generic ‘horde’, and added a lot of variety in their movements and personalities, as we layered in different performances to add more visual interest.

b&a: For the Rathalos, can you discuss what you found worked here for scale? What were technically the hardest bits to deal with skin, scales, wings, muscles and fire for this creature? And what are the hardest parts of dealing with both a flying creature and a plane for that amazing scene that was featured in the trailer?

Jo Hughes (VFX producer): To portray the gigantic scale of Rathalos, we had to come at it on all fronts, with the asset team adding small details across the whole creature, particularly in texture and shading to give breakup; the shot work required attention to the physics of the Rathalos, with speed and weight always being discussed in Animation dailies! Of course every department played a part, for instance the Creature FX team’s dynamics work included wing simulations, and here they made sure to include smaller scale ripples to indicate the size of Rathalos.

Getting the eyes of the Rathalos right took a significant effort. As an audience, our gaze tends towards the eyes, and if the eyes don’t work the whole creature suffers. Rathalos, Diablos, and Palico all had hero eye builds for their final shots. We researched real-world eyes to understand what exists in the animal kingdom and after selecting references worked to match them with texture, shading, lighting and comp working in tandem – all while staying true to the game design.

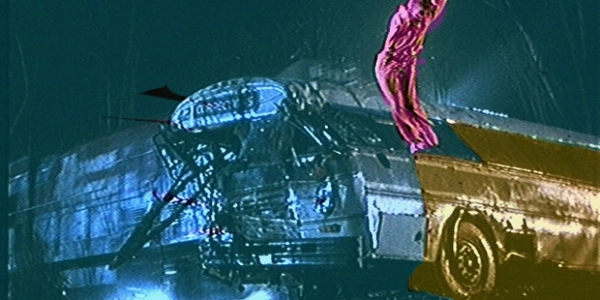

Tom Nagy (animation supervisor): For the animation of the plane sequence, other than the creative performance the biggest challenge was to try and figure out the real-world physics behind the action to make it feel believable. With the interaction between Rathalos and the plane happening at such high speeds, we had to consider things like the relative weight, drag, and wind resistance, as well as their respective flying trajectories. While being as accurate as we could, at the same time we got creative with the framing and composition of the shots, to make sure all of it read properly on screen given the quicker cuts of this action sequence.

Trey Harrell (VFX supervisor): Early on during pre-production, Paul fell in love with a concept image of Rathalos tearing apart a 747. We built our scale outward from this assumption: he’d need to mount a jumbo jet and fit the whole cockpit of a V-22 in his mouth.

I’d say one of our biggest challenges was to ground both Rathalos in the real, physical world with military hardware as well as heighten the military world somewhat — the film takes place in a reality that doesn’t take itself too seriously. The tone is incredibly important there. We’d sprinkle little things like “no step” stencils on the wing of the plane that’s about to be torn off, in addition to a few other cheeky Easter eggs.

How much does a dragon’s wing membrane flutter when moving at 400 miles an hour with wind resistance? How about his soft tissue? We iterated early and often on the big moments of the film with regard to physics and a sense of weight as well as mechanics. We also followed the in-game logic for his fire breath fairly closely.

Rathalos is able to breathe small fire balls at will after a deep breath’s downtime, but he’s able to release a much bigger, sustained blast much more rarely, which required a bit of a conceit. In the film, he has to “charge up” his bigger napalm attacks, giving our heroes motivation for their tactics.