Forwards, backwards, practical, digital—and everything in-between.

Back in May, an on-set report about Christopher Nolan’s Tenet revealed that one of the film’s biggest set pieces involved the fiery crash of a real 747 Jumbo into an airport hangar.

The report spurred on an early discussion about the role of practical effects in modern movie-making, and, certainly, the majority of big shots in the film were achieved practically, while also utilizing digital effects to aid in the storytelling process.

To find out just how some of the biggest scenes, including the plane shot, a car crash, reversing bullets, a collapsing building, helicopters and a number of other forwards and backwards time moments were carried out, befores & afters spoke to visual effects supervisor Andrew Jackson, from DNEG.

Jackson, who also worked on Nolan’s Dunkirk, and previously on Mad Max: Fury Road, was on board Tenet from the very early stages to research efforts for the way that certain shots could be brought to life, whether they be practical or with some digital intervention from DNEG, or both.

b&a: Sometimes, in other films, the filmmakers talk about using a lot of practical effects. But actually in the case of Chris Nolan’s films, he really, really does try and do that, doesn’t he?

Andrew Jackson: Yeah, absolutely. It’s a really high priority. There’s a sort of hierarchy of preference for him. Starting with full 100% in-camera effects, and then if we can’t achieve that, then maybe a 2D comp of filmed elements would be the second best option. A CG element comp’d into a practical background would be the third. Obviously, we can pretty much do anything with CG these days if we absolutely need to but that will always be the last resort with Chris. We do put an enormous amount of effort into finding ways of filming practical effects or miniatures or elements.

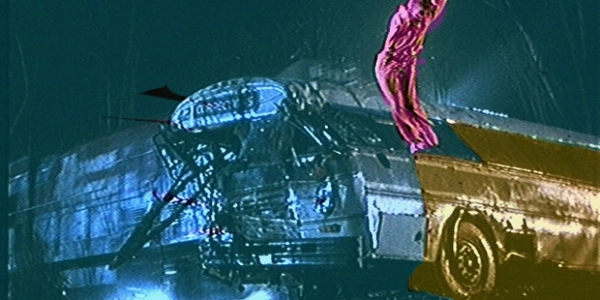

b&a: The plane sequence seems to highlight that the best. What was involved with actually crashing a 747?

Andrew Jackson: I think that’s the best example of the lengths we go to with Chris’ films to do things practically. That plane crashing into a building and exploding is almost all in-camera. The only effects work was some cable removals and there was a little bit of clean-up. It was full-size 747 smashing into a set-built building, and all of the flames, all the collapsing, the jet bridge— everything is practical in-camera. It really epitomizes literally how high that priority is to get everything in-camera.

b&a: But I’m curious, did you go down the route of maybe considering that it could be a miniature shot, or a CG shot?

Andrew Jackson: Early on, we did look at those options. But I think Chris actually came to the conclusion that it was probably not necessarily a lot more expensive to do practically. I mean, it’s a big shot to do a full CG plane and building destruction. But because of the way we arranged it—we went to the Victorville aeroplane graveyard where old planes go, like a wrecking yard. So we bought an old plane that was never going to be used for anything else. It didn’t have any engines. It was covered in pigeon shit. We cleaned it all up and then built a set there.

So, we didn’t have to move the plane anywhere. The place where we went had all the infrastructure for driving planes around. It turns out that it was actually not a crazy expensive way of doing it, it was actually a really practical solution to buy an old wreck of a plane and go to the place where the plane was to film it. It was actually a really sensible solution.

b&a: Were there other sequences in the film that perhaps ended up using something full-scale and practical that you might have thought would be miniatures or digital work?

Andrew Jackson: There’s a lot of Chinook action in the film towards the end, and we did approach that in various ways. We had Scott Fisher’s SFX department build miniatures that were great. We did film those, and we also did a couple of shots with CG Chinooks. But really, the vast majority of that ended up being the full-size Chinooks. We had four of them, re-painted them in the colors that we wanted and they carried real shipping containers around. So really, the majority of the shots involving those Chinooks were real.

I guess that would be an example where on another film you might assume that there would be much more CG work there, but it ended up really being largely in-camera. There is one shot in particular, and it’s there in an IMAX frame, which is taller than the majority of the 5-perf presentation, where there are two full-CG helicopters really close to camera. We did end up making full CG assets. Partly it’s a fall-back position, if we need them we know we’ve always got that.

b&a: Speaking of IMAX, how did the IMAX side of the shoot impact on your work?

Andrew Jackson: The resolution is higher, we’re working at 6-and-a-half K, so everything is done in higher resolution. And the frame size is taller than the 5-perf, which is the general presentation ratio. So, we’re working on a bigger frame at a higher resolution. It does impact the work you do, because everything has to be done at a slightly better quality, slightly more detail. Every aspect of the work that we do is lifted a little bit, because of the IMAX resolution.

b&a: One of the things I’m still a bit bamboozled about in the film was when things are moving forward and when things are moving in reverse. From a visual effects point of view, but also just filming it, and on the practical effects side, how did that impact on your work?

Andrew Jackson: One of the major impacts of the forwards and backwards was actually in pre-production, working out how we were going to achieve those things. We did a lot of work with Chris and all the other departments early on, working out what we wanted it to look like on screen, and then working out how we were going to achieve that.

Even resolving the story line, because if you’ve got a scene with a whole lot of events happening forwards, and intermingled with that, there are events that are happening in reverse, but you’re seeing them from the forwards point of view, then you see them again from the reverse point of view. Now, all of those actions points have to fit together in time.

So what ended up happening was, we used Maya to do previs on one of those scenes—the car chase scene in particular—and realized that blocking that scene in 3D was incredibly valuable because we were able to scrub through it forwards and backwards, and check that all of the story points worked in both directions and the way that they interacted with each other was correct.

Everything had to cross over, and both those stories needed to make sense from the point of view of the characters in the story in both directions. You kind of had to play it backwards with the reverse character’s point of view and make sure that all the events still worked in both directions. It’s very difficult to do that on paper because it doesn’t have the timing. Some of the timing is quite precise, like throwing things from one person to another, for example, or the car crash.

So that previs tool, if you like, became incredibly valuable. We went on to previs a whole lot of the scenes that had a lot of the forwards and backwards action. When I say previs, we weren’t looking at camera angles or even really precise positions of things, it was much more about the overall blocking of the scene, the timing. But it was incredibly valuable for working out how those characters moved around the scenes, when there were forwards and backwards people in the same scene at the same time.

b&a: I feel like it really hurts my brain trying to decode what’s going on sometimes, but that’s also something I really enjoyed about the film.

Andrew Jackson: Well, we all struggled with that. I think it was harder when it was on paper than when you have images to go with it. I read the script four times and I thought that I had a really good understanding of it, that I had the whole thing in my head. And you’d be trying to explain it to somebody else and you realize, ‘Oh actually, I need to go back and check that,’ because as you were trying to explain it, it wasn’t making complete sense.

It was a little bit like using a muscle that you’ve never used before. You had to develop your brain to actually be able to think in this forwards and backwards world. And we got better at it. It was just a little bit like limbering up, stretching, and warming up for an athlete. You couldn’t just leap straight into doing it, solving the forwards/backwards puzzle. You had to kind of work up to it and it took a little while. Everyone definitely got better at it over time during the shoot.

After working out what we needed to achieve, the question then was how were we going to achieve it. That involved a lot of rehearsals with the stunt department, and they did an amazing job. The stunt performers were basically learning how to perform convincingly in reverse. A lot of the action is people performing backwards in the same scene at the same time as people performing forwards.

b&a: Woah, is that really how it was done?

Andrew Jackson: Yep. And so a lot of the scenes where there were reverse people and forwards people in the same scene, they are all there and half of them are performing in reverse.

b&a: Did that need any particular effects ‘treatment’?

Andrew Jackson: There’s really only a couple of shots where we added some extra people. In some of the scenes where there were a lot of soldiers running around in the background, and maybe there weren’t quite enough or they were not doing quite the right thing, we did a couple of adjustments there. Very few. The vast majority of those shots were all in-camera. There was a whole team of people all running backwards. The people who were running backwards often ended up being the forwards people in the film.

Whichever was the easiest to perform in reverse, those people were performing backwards. But it would sometimes end up that we reverse the whole film, so those became the forwards people and the backwards ones were actually going forwards.

b&a: Had you and Chris and the DOP and anyone else, done much of a study into what it looks like when you simply reverse film? What kind of R&D did you do to think about how forwards/backwards footage would appear in the film?

Andrew Jackson: Yes, very early we filmed people doing various things and reversed it and watched that. That was how the stunt department worked, they filmed themselves doing something, reversed it, and then they watched that film and learned how the movement was and the weight a body would feel like in terms of timing. So they were mimicking exactly what they looked like when they were reversed, just from the foot falls and the bounce and how the timing looked. The actors as well, John David Washington was fantastic. He could act very convincingly in reverse. It was amazing watching some of the performers do that because it’s actually really difficult to tell which ones were forwards and which ones were backwards in some scenes.

If there was something like a person being thrown or falling, that had to be shot the wrong way so that those people would, say, leap up off the ground. Those were the kinds of events that defined which way we shot it.

A fairly big part of my input in the early stages was filming things like dust from wheels, and that sort of thing, in reverse. How does that look when you have an inverted car driving? It’s sucking dust into the wheels instead of spitting it out. So, I was doing quite a lot of testing with that. And then there were also discussions about, when you’ve got an inverted object moving through a forwards world, what impact does that have on the environment around it? Does it affect the world in front of it, because it’s going backwards, or is it behind? So, we were looking at simulating little tests of that with just simple particle simulations, as part of trying to resolve what the rules in our film were.

It was very important to Chris that it didn’t feel like magic or fantasy. Like all his films, it had to feel like it was grounded in reality. We also talked to Kip Thorne, who Chris worked with on Interstellar, about black holes and the science of time. And Kip drew a little diagram of an object moving through a field of order, and this little space of disorder in front of it, and the little space of order behind it. The object itself was inverted, so it was like a boat wake with this little distortion of time in front and behind it. It was what we called swimming against the tide. If the inverted object is pushing against the normal flow of time, what impact does that have?

Whether the solutions are visual effects or not, we’re very involved in that process very early on. Because quite often I think visual effects are treated as a separate thing you do at the end and it’s not as integrated into solving the whole film as it is. It’s something I love doing. How can we come up with that, how we can shoot this? I’m always thinking about the whole solution, wherever the solution comes from, whether it’s practical or digital.

b&a: How was the car crash sequence, which we see happening forwards and backwards, achieved?

Andrew Jackson: Again, it was pretty much in-camera. We had cars that we re-built to drive backwards. They had a driver in the back facing backwards. I think it was a clever little trick where you flipped the differential, you turned the differential upside down and then all the forwards gears worked backwards.

So they had a driver in the boot looking backwards, or on a pod on the top if it was an interior scene. Those cars were quite easy to drive at speeds in reverse. Then we had all the various cars, the forwards ones and the backwards ones, surrounding the car that’s going to flip.

The majority of the visual effects work in that scene was getting rid of all the camera cars, because we obviously had cameras everywhere. We only did that stunt once and it was seen from a couple of different angles, but also in both time directions as well. The majority of the VFX work in that scene was getting rid of big camera cars and adding more cars in the background, making sure that all of the cars were in the right place. But the actual flip itself and the cars around it were all real.

There was a lot of cleaning up of the underneath of the car and that sort of thing. One of the biggest effect shots that we did was when the car explodes, and here the world is pushing back on the explosion and it sucks back into the car. That related to that idea of the world pushing back on the inverted effect.

b&a: What about the sailing scene? How was that done?

Andrew Jackson: They’re SailGP catamarans, they’re sort of Formula 1 racing yachts. They have hydrofoils and as soon as they get up onto the hydrofoils they’re incredibly fast. I think they do 50 knots or something like that. We were in really fast ribs and they were overtaking us.

The actual scenes that we shot had the real actors on the real boats, sometimes with the crew on the other side so that we had the actors on one side and the crew who were actually steering were on the opposite side. We had wider shots with the crew dressed up as the main cast. We also towed the boats with another fast boat, without a sail. They were less dangerous without the sails on, so you could just tow them around where you wanted. We added the sail back into a couple of shots, and we did some face replacements in there, but not very much.

b&a: Then there’s the opening opera house scene. Can you talk about the crowd there, the bullets and the explosions?

Andrew Jackson: I think they had 3,500 extras, and we went to an old concert hall in Estonia, in Tallinn. It was amazing building there that was in quite a bad state of disrepair. But it’s an amazing building, so the production cleaned it up and we shot there. All the bullet scenes were all practical effects, squib hits. The people were all real, the only area in there that we were involved with was the reverse bullet hit. That was the first time we saw a bullet hit disappear. That was the first major clue that there was something odd going on.

When we see the big explosion at the end, from the interior, we did a little bit of work on that to adjust the timing. But, they did actually do a practical explosion and we had to put the crowd back in under the explosion because they were too close to where the actual explosion was. So, we did that but with 2D crowd elements.

b&a: We talked a little about IMAX, but what about just generally shooting on film—how does that affect the VFX process?

Andrew Jackson: One of the biggest impacts is having to choose what to get scanned, and not necessarily having access to absolutely everything that was shot as easily. So there’s a little bit of a time delay when you need to get something additional scanned. Working with Chris, it’s not just shooting on film but he wants to finish optically as well. Ordinarily he doesn’t use a DI, all of the visual effects work is output back to negative and that gets cut into the original neg, and then color-timed optically.

Shooting digitally, though, has other challenges. You end up with a lot more takes, a lot more footage than you do when you shoot on film. I think it does kind of sharpen people’s focus a little bit more when you’re shooting on film. There’s a sense around a lot of digital shoots where people just leave the camera rolling as if there is no impact. But actually, there is quite a lot of work involved in managing the hours and hours of footage where the camera is just rolling. I do think that even though it may be harder in some ways, probably there are advantages as well, shooting on film.

We actually had a little IMAX visual effects crew that we carried for the whole of the shoot. We would shoot elements and occasionally pick up extra little bits and pieces for Chris as well, when there was something they needed but had moved on. Other times we would go ahead of main unit and get something up and running before they arrived. The racing yacht scene, for example, we went a few days ahead and we were getting the cameras working on the yachts, and working on how we were going to mount them, what angles worked.

In general, shooting on film, can be more of a challenge because you’ve only got your 3 minute rolls. A 1,000 foot roll of IMAX only lasts a few minutes. And then if you’re shooting miniatures and you want to over crank it, then you’re down to 1 1/2 minutes a roll. It had a much bigger impact on us for Dunkirk than it had on Tenet. On Dunkirk we were shooting miniatures over the water from a helicopter, and so we only had a minute and a half in the camera. We had to go back, land the miniatures, land the helicopter, reload the camera. But, it did make it very satisfying when you achieved the shot you wanted.

b&a: Are there any other scenes you wanted to highlight, Andrew?

Andrew Jackson: The end scene had one of the biggest involvements for us. It has a building that simultaneously implodes and explodes. It’s where half of the soldiers are forwards and half of them are backwards on both sides. So even on the Tenet soldier side, half the team is moving backwards in time and half are moving forwards in time.

There’s a central area in that battle where there’s a building. When we find it first, the top of the building is sitting on a pile of rubble, as if part of the building has been destroyed and the top of the building is sitting there. We find it like that from the protagonist’s point of view. But for the people coming from the future, they find the same building with the base intact and the top destroyed. So it’s the same building in two different states, depending on whether you’re coming at it from forwards or backwards.

There’s a moment in the film where both sides fire rockets at the building, one of them basically sends a reverse rocket at the base, which re-builds. And the other one sends a forwards bullet at the top, which collapses. So the building re-builds and then collapses the other way around. It’s this nice little symmetry of the building going from the bottom destroyed to the top destroyed, depending on which direction you’re watching it. But the two explosions happen at the same time.

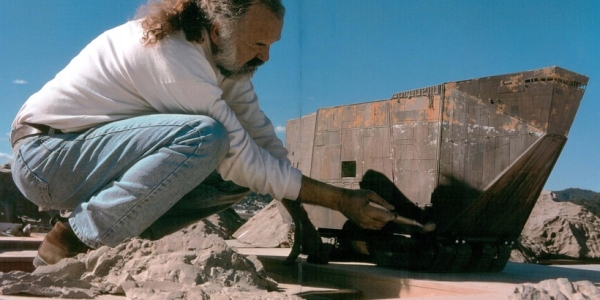

As with everything, Chris and I were looking for ways that we could film practical effects for that. So we came up with a plan that involved building some large miniatures. They were 1/3 scale, and we built two buildings, 1/3 scale and we blew them up. One, we’d blow up the bottom, one, we’d blow up the top. We matched the camera angles so we could comp those two together. It was a comp of two separate miniature explosions.

We filmed it from two different angles, on both buildings, so we had two separate angles of the same event, from two different directions. One of them got a bit overcome by dust—the camera was swamped so it lost the view of one of the sections. We had to introduce a little bit of the element back in just to make the story clearer. But the main components were practical.

That was a good example of the whole integration of visual effects, special effects and the art department all working together to come up with a solution for that event. That was probably the biggest visual effects / practical effect on the film.

Andrew Jackson is the final keynote speaker at VIEW Conference, find out more details here.