The ‘Wolfwalkers’ director is one of the speakers at VIEW Conference 2020.

At VIEW Conference 2020, one of the many VFX and animation speakers will be director and Cartoon Saloon co-founder Tomm Moore. Here he will discuss his latest animated feature, Wolfwalkers, co-directed by Ross Stewart. The film just premiered at Toronto International Film Festival.

Moore is perhaps best known for directing The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea. He’s also worked as a producer, art director, storyboarder, animator and Illustrator on a range of projects. To gear up for VIEW, befores & afters looks back at the origins of Cartoon Saloon with Moore and how The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea were made.

How Cartoon Saloon started

The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea, were both nominated for Academy Awards for Best Animated Feature. That’s a prestigious feat for any animator, but it is perhaps even more impressive considering that Moore and his collaborators made those films by starting their own independent production studio, Cartoon Saloon, in Ireland.

The company grew out of out a group of Irish filmmaking friends Moore had collaborated with at Ballyfermot College in Dublin, where he studied classical animation. During that time, in the mid- to late-1990s, Moore had noticed a change in views towards hand drawn animation. “There was something in the air then about hand drawn being under threat,” he says. “I started college in 1995 and that’s when Toy Story came out. I remember the muttering and mumbling. We actually watched Toy Story and Balto on the same day with classmates and there was a lot of discussion about how was hand drawn animation going to face up against CG? I was naive. I actually thought that stop-motion was the traditional art form that would be affected. But it was hand drawn which was dominant then that was talked about as being under threat the most.”

After Cartoon Saloon had been formed in Kilkenny, the studio actually used that experience to, as Moore describes, “look at everything hand drawn animation could do to re-invent itself and re-imagine itself.”

Inspiration came initially from director Richard Williams’ 1993 film The Thief and the Cobbler which had utilized pieces of Persian art in many scenes. “I thought we could do something similar with Irish art with both hand drawn and two-and-a-half-D animation,” recalls Moore. “That’s when we started looking at the ‘Book of Kells’ and how that had really inspired Irish art and calligraphy and manuscripts, to see if there was something there that we could adapt to hand drawn animation. It’s kind of backwards! It’s not the way I would advise anybody to come up for a story for a film, but it’s something that worked out so well.”

Although a hand drawn aesthetic was first and foremost in their minds when starting the animation studio, Moore says he and the filmmakers at Cartoon Saloon are not against the use of computers at all. “I always think we’re really lucky in a way to have computers,” he says. “We can use them to make animation that’s very organic and hand made and timeless that way. So The Secret of Kells was a real fusion and the first step in that. We were at the time experimenting with what we could do, mixing with hand drawn and computer techniques.”

Moore developed an interest in animation and drawing when he was young. A visit to Don Bluth’s studio in Ireland at the age of 14 at first made him think the animation process was far too labor intensive. “It didn’t seem very feasible that you’d get to tell your own stories through animation,” Moore says. “It wasn’t until I went to Ballyfermot that I got the bug again for animation. Luckily for us by then there were some new technologies that still let you do hand drawn animation but in more efficient ways.”

The initial establishment of Cartoon Saloon was tough. When the idea to make The Secret of Kells pushed ahead, the budget was low but the enthusiasm was strong. “We had really assembled almost a ‘coalition of the willing’ who were willing to keep working and living in a fairly student-like lifestyle,” describes Moore. “And Kells benefited in a way from the fact that we were so naive and enthusiastic that we didn’t have a big budget to spend a lot of time on concepts. But we didn’t need the budget – we were living off beans and toast!”

The secrets of The Secret of Kells

The Secret of Kells (2009) follows the adventures of Brendan (voiced by Evan McGuire), a boy at the Abbey of Kells who goes on a quest to help complete a magical book brought to the Abbey by a master illuminator, Aidan (Mick Lally), much to the dismay of Brendan’s over-protective uncle, Abbot Cellach (Brendan Gleeson). “The story, really, is about artists and art being important,” expounds Moore. “We found the story in the history and legends around the ‘Book of Kells’, which is where we’d traced a lot of the art that would be described as Celtic. That was seen as a visual high point in Ireland.”

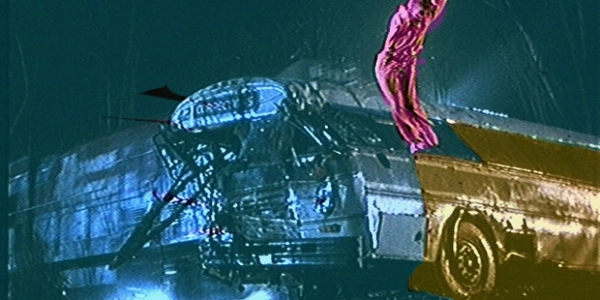

The traditional artwork in the legendary book directly influenced the approach to animation in the film. “All the hand drawn character animation was done with paper and pencils,” notes Moore, who co-directed Kells with Nora Twomey. “The backgrounds started with hand painted textures and hand drawn elements like trees or buildings. We’d draw them on big sheets of paper with pen and ink or pencil. We used a little bit of Flash for background characters such as in the dream sequences. Then it was all digitally composited.”

The luscious textures of The Secret of Kells were explored early on in the concept stage, with art director Ross Stewart referencing not only the ‘Book of Kells’, but also such inspiration as Gustav Klimt paintings, stained glass designs and impressionist artworks. The animation process began with storyboarding. Since the film would ultimately be animated in several locations across a number of studios, the boards had to be quite precise. “We could only do the blueprints here in Kilkenny and just the main backgrounds, the main key poses for the animation and about 20 minutes of full animation,” outlines Moore. “Storyboards helped figure out the angles and compositions. Then those would be edited. A second pass was done in layout, where it was refined and some more changes done. What followed was key posing stage where we would try again. Only after that did we have the sequence working in very precise black and white form that we could send out to be animated.”

The style of animation in Kells often allowed for the book’s magical properties to be explored in fun ways, such as when Brendan first flicks through it and Celtic designs literally pop out of the pages. “All of that had to serve as the character’s journey,” notes Moore. “We had to make it clear that we were showing the world through Brendan’s eyes or how the world might seem through a kid living in Ireland at the time. Also, the distance between imagination and reality was blurring – and that’s what we used as an impressionistic technique throughout the whole film. It allowed us to be quite free with the art direction. It gave us permission to show things on screen that might only be seen by the character or might only be in the character’s imagination.”

On his quest to finish the book, Brendan ventures into the forest and is saved from wolves by a fairy named Aisling (Christen Mooney). Aisling, marked by her striking long, white hair, “came late in development,” admits Moore. “We had a problem early on in the scripts where because it was set in a monastery it felt a bit like a submarine movie – it was so male and it just felt wrong. Then working with the screenwriter Fabrice Ziolkowski, we realized it also felt wrong for that period because then the Pagan aspect of that period was very matriarch, so we wanted a stronger female influence. But we didn’t want a love story so we played with the idea that Aisling is like an antagonist to Brendan.”

“I grew up with three younger siblings, so we had the idea of a pesky little sister who was better than Brendan at everything and there was a little bit of one-upmanship in their relationship. I think that’s what kids really relate to. I think the Brendan and Aisling relationship, even though it’s a small amount of screen time, is really the heart of the film. The way they play off each other is what a lot of kids can identify with.”

At first, the filmmakers gave Aisling black hair, but, says Moore, “it soon hit me that white hair would connect the characters. We also thought it was cool and mythical to give Aisling long white hair and align her with Aidan and his cat Pangur Bán, that way, as distinct from the other characters.

Moore and Twomey considered that strong, and local, voice talent would be required to tell the story of Kells. “We’d actually contacted Brendan Gleeson really early on,” says Moore, “really naively before we’d put the budget together. But he’d always been really supportive. So when we called him up and said we had the budget he was already a pretty big star in Ireland. We’d even changed his character a lot but he was very happy to support us and record voices.”

The roles of Brendan and Aisling were harder to nail down. “You want to use a real kid – you don’t really want an adult to pretend to be a kid, suggests Moore. “But you don’t know in that tiny window of time that you have to record the kid whether there’s someone out there who’s right. The problem, to be honest, is that sometimes kids are ruined if they’ve been through acting school. If they want to be an actor they’re not really the right choice, because they’re a bit precocious and they overact a little bit. So we needed to find kids who hadn’t yet been ruined by wanting to be actors! We traveled the country looking for them and I felt we were really lucky with Evan McGuire and Christen Mooney.”

Moore says the filmmakers were also lucky to score the services of Bruno Coulais and the group Kila, who were responsible for the music. “The way it worked was, Bruno sent keyboard demos he had done, and then I had a couple of meetings with Kila, and then we had a short recording schedule where all the arrangements were recorded right at the end of the production. We were just so lucky with the talent because we had no time. It’s always like that with animation, you just labor away for years and years on the visuals, then suddenly you hear the music and it’s fifty per cent of the film and it can all be recorded in a week, and suddenly the film is fifty per cent richer.”

The Secret of Kells won a slew of animation awards and much praise during its release, but the Oscar nomination came as a complete surprise to Moore. “The nomination really came out of passion,” says the director. “An animator had seen it in Dublin and started spreading the word in LA. Then different key players in the LA industry saw it and started talking about it, unbeknownst to me. So by the time the nomination came up, it was a real surprise and I only found out retrospectively that we had all these sorts of underground grass root champions amongst different animators and people in the Academy and in the LA animation community. It was a huge validation of all the work over 10 years that so many people had put into it.”

The story of Song of the Sea

Telling Irish stories remained important for Moore in his next feature, Song of the Sea (2014). This film told the tale of a young boy named Ben (David Rawle) whose mother, Bronagh, leaves Ben, his father Conor (Brendan Gleeson) and a newborn sister, Saoirse, who by age six has not spoken. Eventually it is revealed that Saoirse is, like her mother, a half-human, half-seal selkie.

Moore had the idea for the film after holidaying with his wife and son at a coastal location and seeing some dead seals on the beach. “That was because of a cull in 2004 or 2005 where fishermen were killing seals,” says Moore. “My son really loved animals and we’re all animal lovers in the family and we were quite disturbed by it. Someone there told me if wouldn’t have happened years ago, that there was a belief that seals could be the souls of the dead and that people who were lost at sea became selkies. It was a belief system that connected people to the landscape.”

The director also encountered a book called ‘The People of the Sea’, a collection of fairy and selkie stories from Scotland. “It made me think about stuff that was going on when I lost someone in my life,” he says. “Losing somebody you love was really part of the whole selkie mythology. I thought between the environmental connection of connecting people to the landscape and the underlying theme in those stories about dealing with loss that there was a very potent story to explore as an animated feature.”

Moore looked to take what he had learned as a first time director on Kells and apply it directly to Song of the Sea. “I learned so much developing and getting Secret of Kells off the ground that I wanted to apply it to a second film. This new film was a little bit more focused on folklore and storytelling and how it could invigorate that for a younger generation. I do see Song of the Sea as a lot more story focused while Secret of Kells is more art direction focused.”

In terms of the look of Song of the Sea, Moore is quick to acknowledge that he was heavily influenced by legendary Japanese animation director Hayao Miyazaki. “He was able to mix in with a modern story some of those older beliefs in Japanese culture,” suggests Moore. “I was inspired that he was able to take his culture and his background and be true to it and not package it up like a product but speak from it. It gave you a little window into Japanese culture, but it was packaged into his films in a way that was international – you didn’t need to know a lot about Japanese culture to enjoy it, but the more you knew maybe the more you enjoyed it.”

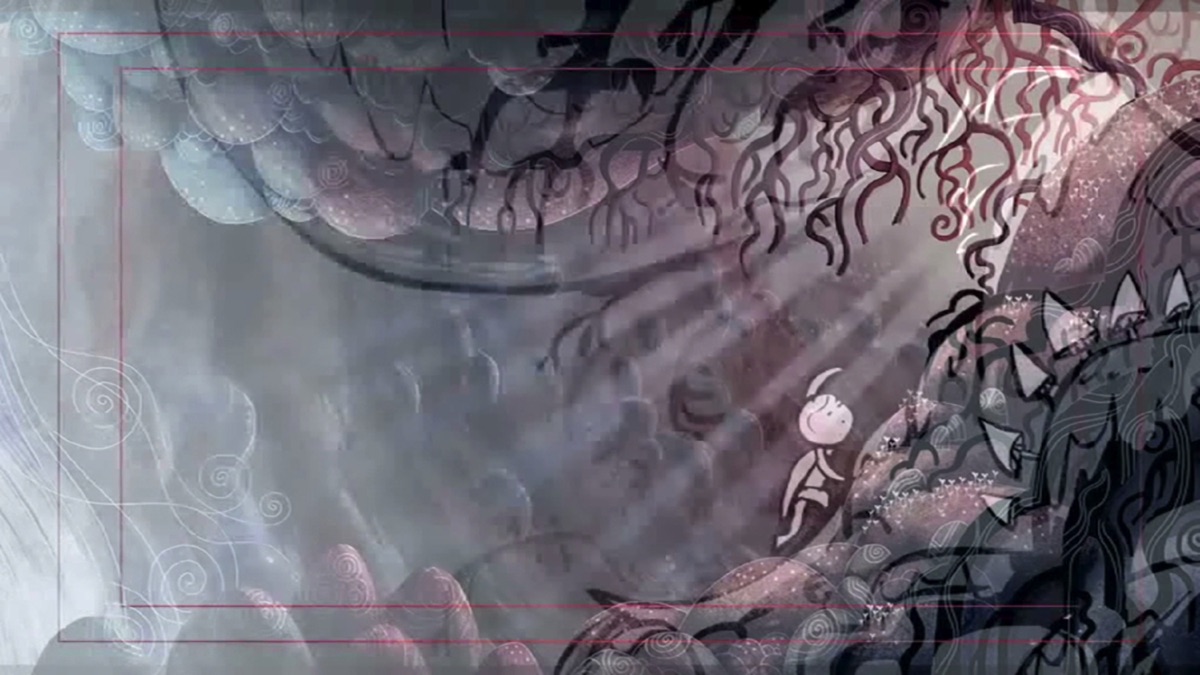

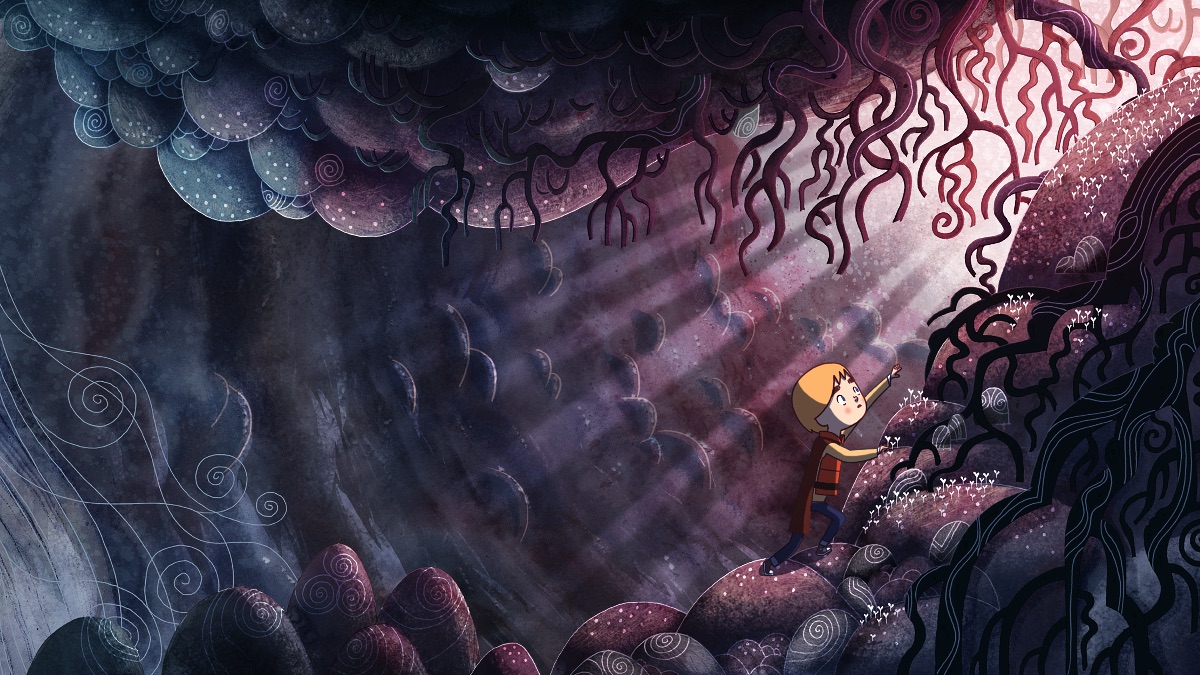

Moore adopted several animation styles that would match the progress of Ben’s journey with his sister. “I wanted it to be more like a picture book for the majority of the film where everything was represented an illustration that read really clearly,” he says. “As the main character Ben got freer and freer of everything that was holding him back and freer from the resentment towards his sister, we started loosening up the camera, and that led us all the way to being able to have the sequence with the flying dogs and the underwater sequences where we were really able to have the camera moving everywhere. Those later sequences had a lot more power to them when we really did start moving the camera.”

Backgrounds for Song of the Sea were initially planned as watercolors drawn with a sketchbook feel, but over the course of the film’s production art director Adrien Merigeau introduced several other modern art influences. “He referenced the abstract work of Wassily Kandinsky, for instance,” describes Moore, “and even saw parallels between old carvings and rock art with the Irish art we wanted to use.”

“What that meant was that we ended up with even more of a hybrid style than we had had on Kells,” adds Moore. “Every background would start with a watercolor painting or a sketch. Most of the backgrounds were drawn on paper with inks. We used a trick of having pencilly lines in the forest but mainly ink lines for the rest of it. That would then be combined in the computer and Photoshop. Then quite a lot of work was done in Photoshop to create the final look. It is interesting to see how loose the backgrounds became at the watercolor and ink stage – it almost become a little sheet with elements drawn all over it and a little game you had to put together. The actual background was all assembled from little hand drawn elements all assembled in Photoshop.”

During moments in the film where an interspersed story or memory was being told, the animation would take on a slightly different look to the main action. “In these sequences,” describes Moore, “we had this idea of a blobby water color effect or a little vignette where we even would show where the paint ended at the end of the page. It felt more like a half-remembered thing and more dreamy than the rest of the film which has lush detail right to the edge of the screen.”

Song of the Sea found an audience in both adults and children; Moore in fact took advantage of the fact that his wife was a primary school teacher. “We’d actually show her class every iteration of the animatic. One note we got early on was that aside from all the funny characters and mythical creatures, one of the key things that kids really identified with was the sibling rivalry. So we were able to play it up in various iterations to the point where Ben was almost completely unlikeable as a kid and so we had to dial it back.”

The songs of Song of the Sea were produced by Bruno Coulais and Kíla, with Lisa Hannigan contributing the main vocals. Moore says he thinks the film benefited from these artists also providing ideas for sound design in key moments. “It was really interesting,” notes Moore, “during recording sessions I would bring them storyboards and parts where I might be stuck and they would bring ideas and sometimes music would answer a story problem. For example, Bruno thought we might not need as many flashbacks to the mother – we could just use Lisa’s voice and thread it through the score. So he used the voice almost like another instrument in the final mix and that allowed us not to have so many visual cues to the mother and sometimes just give aural cues.”

You’ll be able to hear more from Tomm Moore in his talk at VIEW Conference 2020. The conference runs from 18-23 October, in both physical form and online, available globally. Click here to register. Group discounts are available; write to info@viewconference.it for more details.

befores & afters is a VIEW Conference 2020 media partner. Ian Failes will be hosting a number of online sessions at the event.