Harrison Ellenshaw breaks down the planning, painting and compositing of the classic shot.

The art of matte painting has captivated audiences since the dawn of cinema. And if you ever needed to find a film to showcase so many different matte paintings – and varied techniques behind them – that certainly could be The Empire Strikes Back, which is on the verge of celebrating its 40th anniversary.

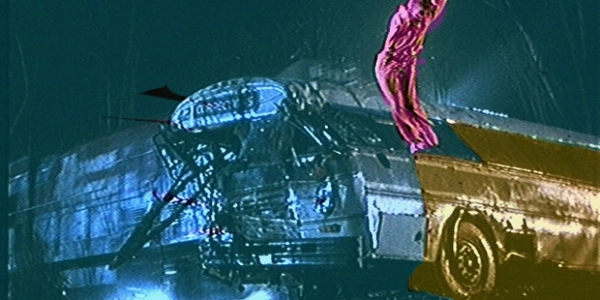

One matte painting in Empire has always stayed with me. It’s the shot of Boba Fett’s Slave 1 on the East Landing platform at Cloud City, with Han Solo frozen in carbonite being loaded onto the ship. It might seem like the shot has all the trademarks of a typical matte painting, i.e. a live action element composited into a wider painting, but it’s not until recently that I was reminded the Slave 1 ship in that shot is actually a photograph of a miniature incorporated into the finished painting.

So, to celebrate Empire’s four-decade history, I decided to speak to the ILM artist behind the Slave 1 shot, Harrison Ellenshaw, who was also the film’s matte painting supervisor. Here, Ellenshaw explains, in his own words, how this particular visual effect was imagined and why it was approached a little differently to other matte paintings in the film.

‘A lot of people thought it was cheating’

Harrison Ellenshaw: I’d been working on The Black Hole at Disney in Burbank, so I got there to ILM, which was then up in Marin County, north of San Francisco, late.

The storyboards by Joe Johnston and Nilo Rodis were fantastic; they had designed the spaceships, and Ralph McQuarrie had designed some of the spaceships, too. Slave 1 was Nilo Rodis’ design. It always looked like a steam iron to me, but Nilo said, ‘Well, I took it from street lamps.’ I think one of the things that make it look so cool is it doesn’t look like a spaceship as we think of spaceships. It doesn’t have fins. It doesn’t have a pointy nose.

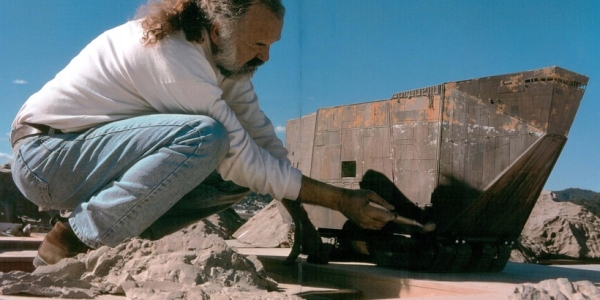

The model for Slave 1 had been finished, and they had shot the motion-control photography.

Now, since I was coming in a bit late, I thought, why don’t we do things a bit differently, that is, use a photograph of this thing. It’s a technique that nobody really said much about because a lot of people thought it was cheating.

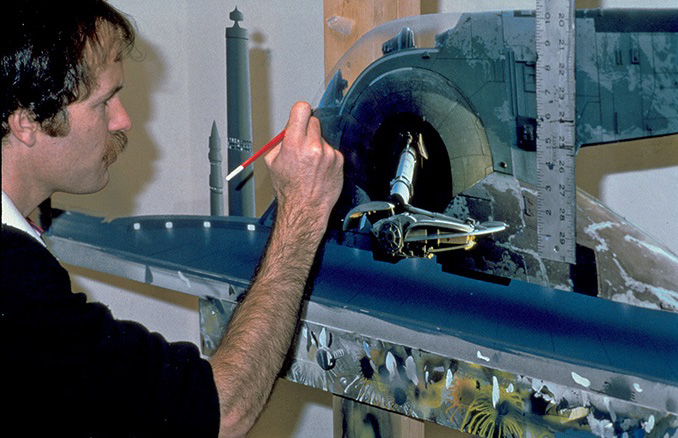

The shot happens at magic hour on Cloud City; there needed to be a real glow to it. So we took the model outside in the parking lot of ILM and we waited for a magic hour and I took my Hasselblad camera and I photographed it with natural light, with the cross-light of the sun just as it was going down. Then we took that to a still lab and had them blow it up onto color print film. That’s what got placed on the glass.

I then started modifying some of the photography of Slave 1. For example, the cockpit – that wouldn’t photograph right, so we cut the cockpit out and then that was painted. I airbrushed in a little area for that. In the background, one of the buildings was also a photograph of a miniature, and then I painted some other ones, too.

Matte painting materials

We painted on the clear window glass. There’s the myth that it was shower doors, which is total bullshit. Has anybody truly looked at a shower door? No, it was just clear window glass. You don’t want it to be too thick because it bends the light as it goes through.

I can’t remember the name of the window glass company who made them, but instead of being in a wooden-frame, they were in a metal frame. The trickiest part was since we painted in acrylics or Gouache. We had to find a good primer. I had learned about Krylon flat white paint when I was working at Disney. We’d spray that on the glass and it created a very nice primer.

The art of clouds: matte painting

So, clouds. Here’s the little secret behind that. It was a big fortune for me. Because after Ralph McQuarrie had done his work on the illustrations for the film. George didn’t want to let him go, so he assigned Ralph to me. So, it thrilled me. He and I painted in the same room and I got to know Ralph on a very personal basis and heard his war stories. He was such a gentleman.

But then I had to confront the reality that Ralph’s clouds were ‘illustrator’ clouds. They didn’t look like real clouds to me, and I didn’t want to hurt his feelings. And, who am I to tell Ralph McQuarrie what to do! Theoretically, I was his boss. So, what I ended up saying was just a little manipulative.

I said, ‘You know what, Ralph, you’ve got so much to do. I think you should do one of the Cloud City shots when they walk out and meet Lando on the platform.’ He had done just a beautiful illustration for that, and I figured he could do the final shot. So, I asked him to do the wide establishing shots, and he just did such an amazing job on them. But, they were my clouds in the end.

Finalizing the shot: Matte painting

After we made the blow-up that we shot outside, we cut that out. I put it on the glass. I added the other stuff. And then behind that was a piece of masonite with the clouds on it. Then we shipped it off to Van Der Veer Photo Effects in Hollywood and they added Han Solo in carbonite and the men and Boba Fett walking up the ramp that had been shot against bluescreen in England.

The optical department at ILM simply didn’t have time to do it. I had a very good relationship with Greg Van Der Veer. I sent the elements down there and talked to him I think once on the phone about it. He got it and put it together. The shot got a good response when we showed it in dailies.

Managing the making of matte paintings

On Star Wars, we probably had maybe a dozen matte paintings, and then Empire had 82 or 83. When I got there, it was a mix of experienced people and some new artists. However, they had not enough experience in doing so many paintings and how to organize the work. So I kind of hit the ground running.

It was very busy, especially during crunch time. We’d be bipacking shots and sometimes make some rookie mistakes. I remember seeing a shot of the stormtroopers coming out of a doorway, and the animation we had put in upside down. So the animation was coming out of the top of the frame and they were shooting from the bottom of the frame.

But I was very fortunate because there were some great innovations ILM had come up with. For example, instead of using rear projection onto a painting, they were doing front projection, and that was really clever. Every technique has its issues. For example, you can see the reflection of the lens of the projector in the blank spot of the glass.

So then, somebody came up with the idea, what if we tilt the glass? The immediate thought was, well, you’ll see a difference in the perspective, but you only have to tilt it a little bit. There was so much great problem-solving going on. It was a great honour for me just to be part of the process.

My thanks to Johnny Banta for helping to make this interview possible.