A practical effects explainer

If you’ve been keeping up with the latest in effects news, you probably already know that Chris Sanders’ The Call of the Wild features a CG dog called Buck (in fact, all the dogs in the film are CG) acting alongside Harrison Ford’s character, John Thornton.

You might also have seen that actor/stunt coordinator/movement coach Terry Notary donned a capture suit during filming as a stand-in for Buck. MPC then created the canine performance.

But not all the effects in The Call of the Wild were digital. Many scenes were accomplished with the aid practical special effects, including the snowy setting (fake snow!), an ice fall (fake ice!) and the river (fake river!), which they actually had to construct twice.

These moments were overseen by special effects co-ordinator Jeremy Hays working hand-in-hand with other departments on the film. Hays also aided in helping to sell moments of on-set interaction between the live-action actors and the non-existent dog, as well as sledding gags and the final cabin fire. Here, he breaks those major practical effects down with a whole bunch of on-set imagery and videos.

A (real) running river

Jeremy Hays: The creation of the river near Thornton’s cabin was a collaboration between the art department and practical special effects. The story called for a 300 foot section of flowing river to be created for various scenes that would involve panning for gold, swimming, canoeing and a few other interactions with Thornton and Buck.

The river itself consisted of four sections; the water input area (upstream), the rapid flowing section (Buck and Thornton start on their journey), the slower moving meander (swimming and panning for gold), and the larger lower catch basin (down stream), which was created entirely from scratch in an extensive dirt lot on the Sable movie ranch in Santa Clarita, California.

Construction first shaped the river by using large excavators and front loaders to move dirt around to create the varying widths and depths of the river, to include the large water basin on the downstream end and the back splash input area upstream. A foundation of shot-create cement with steel rebar was put in place to retain the water and allow for certain points of connection for canoe rigging secured into the river bed.

A dam was created between the slow moving meander and the large lower catch basin with removable planks to help adjust the height of the water in the river during filming and also to help filter out the large floating debris (like crew shoes and hats).

Additionally, since this river was entirely outdoors and exposed to various uncontrollable elements (wind, dust, insects, wildlife, etc.), an enormous amount of filtration was needed for water clarity as well as making the water safe for the actors and camera operators.

Water would be consistently filtered through three large sand filters to remove medium sized dirt and particulate, as well as an elaborate ‘sock and bag’ filtration system to rid the river of the super small micron sized particulate and organisms in the water as well. Water PH and quality were monitored and adjusted on a daily basis to ensure the crew could safely work within the water.

Not only did we build this river system during principal photography, we had to come back 6-7 months later and build it again for more additional photography.

For the canoeing sequence, there were a couple of setups. There was the section of the river that we built that had flowing water in it. That was for the beginning of his journey and the end of his journey, and some bits and pieces set in less turbulent water existed in the river set that we made. Then there was the scenes with the canoe. These were shot in British Columbia with a stunt performer. Then there was a bluescreen setup with Harrison on a gimbal.

There were two or three shots that involved the canoe on a gimbal that were big camera moves, big cinematic sweeping camera moves where the whole background was bluescreen anyway, and they wanted to tie it into a motion control camera with the motion base.

Dog interaction

Since all of the dogs were digitally modeled, we had to create any real-world in-camera effects, say, when Buck knocks something over or if he tears up a rug or jumps on beds. We had to basically simulate the movement of that character doing those things and what the end result would be.

Because Buck was going to be all-digital, there was this rare opportunity to have the movie entirely pre-visualized [Halon Entertainment led the previs effort]. That allowed us to figure out scene-by-scene what Chris Sanders wanted and what Erik Nash, the VFX supervisor, needed, and how the story was going to play out.

Interestingly, sometimes what is previsualized by the director or previs team – that they see in their mind’s eye – may not necessarily work that way in the physical world. For example, things don’t always fly in the way that they would in animation form because of gravity.

Ultimately, every time there was an instance where Buck would have to do something, you had to put yourself in this mindset to imagine there’s this invisible dog and they’re doing this behavior or action and you have to think, ‘Well, what would it look like or what would happen?’ And then you just mimic that with either cables or some form of mechanical device or wind or air blast.

There were stuffies that were on set, as well as Terry Notary. Some stuffies were the relative size of the dog to help get your head around the spatial relationship. Very seldom did the stuffie do anything other than just act as a stand-in. There was a dog that we had on set that they would use for interactive lighting, basically by walking it through the set. They put him up on the table, that kind of stuff, just to film a pass, or they’d take photographs of him so they could see how the light would react.

We also made dog shapes for when Buck breaks out of the crate, at one point. We made the shape of Buck coming through so that way the pieces or items that would be flying through the air, if they were to bump against something, it’d be representative of where they were going to animate Buck into the scene.

The art of fake snow

The majority of the movie takes place in the snow in Yukon, but we filmed it basically all in California, where it was hot and dusty and windy. So a big portion of what I had to do was work with production designer Stefan Dechant to create a winter snow environment on location.

The thing about snow products is there are several different types of them and none of them are all perfect. Shaved ice, which is what we used a lot of, looks really great and behaves a little bit like snow. It has light, it glistens like snow, but of course where we were shooting it melts really easily and you have to deal with water drainage.

In some of the sets, it was difficult to actually get the chipper in there to blow the snow. But on sets where we were on a stage, we would use a mixture of Epsom salts and a plastic snow called ‘display snow’ that looks very much like snow and behaves a little bit more like powdered snow.

All the trees or any kind of set dressing where you wanted the snow to land on ledges or on the tops of light posts, that tends to be a cellulose snow product or a paper snow product that you can blow out of an insulation blower and you can dress the set with that.

Sometimes we would shoot paper snow on the ground as well. It works pretty well for snow because it doesn’t melt. And if you’re shooting a set that’s going to be there for a while, you don’t have to worry about clean-up as much. It doesn’t quite behave the same way that snow does, but I think it’s been seen in so many movies now that people are starting to think that’s what snow looks like.

We also had a snow we called polymer snow that is basically like the stuff that absorbs wetness in diapers. It’s a white powder that absorbs water really easily and expands in volume. That can be super slippery but it looks like snow. So for some of the sled scenes, where we had to have the sled sliding back and forth on snow that was a little bit more slippery, we used that product.

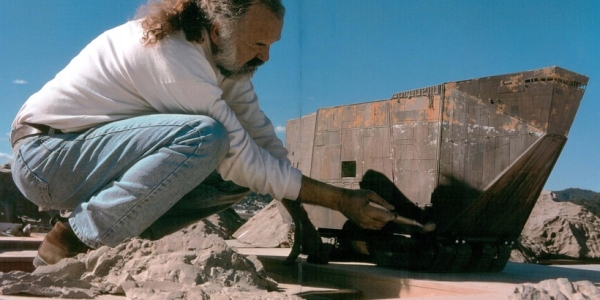

Going sledding

For the sled shots, the plan was to pull them through the fake snow mechanically and then there’d be CG dogs added. Erik Nash asked if there’d be a way to make sure the sled felt like it was being pulled by individual dogs that might have different cadences in their run.

So, in the beginning, maybe the sled has a little bit of a slow-then-fast pull feel and then once it gets up and going, it has a different type of a feel to it. And because there are no dogs, Erik said, ‘All I really care about first and foremost is that the sled is sledding on something that makes the sled behave the way that it would in real snow.’

We had a couple sled moves that we were really trying to get in-camera so we developed this whole track system with an arm that pulled a sled around a corner to make it slide. It all worked really great. But the whole idea was they wanted to put the actors in this particular rig. As it progressed, they realized there really was no way you can get the actors to perform confidently in that type of rig. It has to be stunt people. And then they were like, ‘Well, if it’s got to be stunt people, we might as well just put the hero actors on a gimbal and recreate the scene that way.’

So then the rigs that we used to initially try to create the scene became a sled simulator rig. We would put cameras on the sled and the arm that we were pulling it from and basically monitored how the sled would behave during these different moves. And then when they went into using the gimbal and putting the sled on the gimbal, they could analyze those camera moves and basically mimic them through the motion of the gimbal.

Falling through ice

One of the characters – Françoise (Cara Gee) – falls through the ice in a river. We had to build another section of river that flowed that had a breakaway section that she could fall through and then Buck our hero character dives in and rescues her.

First we had to create a tank of water that we could put a current in. We built a steel structure that we buried in the ground and then created a current by drawing water from one end on the downstream part of it, and then we would suck water from one end of the tank and re-deposit it on the upstream part.

We’d recirculate that water down the length of the tank so that we could have a flow. So when the actress fell through the ice into the water, all the ice pieces and the actress would go down and underneath the ice in the scene. So we created a current first and then we basically worked on creating various ice decking pieces that were strong enough that you could walk on but that you could actually see through.

Then we had our breakaway section, which was a jigsaw puzzle of various breakaway sections that pieced together in a certain way. And then a clear acrylic trapdoor mechanism that was underneath the ice, but on top of the water, right at the very surface of the water, that opened like the way elevator doors do from the middle out. But imagine that they’re not vertical, it’s laying flat horizontal.

The actress would stand on the the breakaway ice section in the middle of the tank and, those doors being clear, you can see through them and iced over. She stood on the middle section where those doors part and open up. It was a pneumatic system where it pulls these doors open fast.

And the floor that’s underneath the ice – the clear floor that’s underneath the ice – opens really fast, which then makes the surface that she’s standing on brittle so that she breaks through the ice at the moment that they cue the doors to open. And then they open up far enough that when she goes down into the water, she goes underneath the ice pieces and the water surface is right there where the ice meets the water.

Cabin on fire

Our hero Buck pushes the bad guy into a cabin while the cabin’s on fire. We had to create this cabin that we could shoot in and then rig it so the roof would collapse where all the beams and all the grass that was on top of the cabin would fall down inside while it was on fire.

There’s a stunt sequence where the dog pushes the bad guy through the door. As the stunt person is being launched through the door and breaks into the cabin while it’s on fire, the ceiling collapses on top of him from within.

There’s camera personnel inside there and the stunt person. We had basically rigged a lightweight balsa roof with beams that we fireproofed and then lit everything on fire and did the sequence with the roof collapsing.

It was a good kind of action, a very dramatic kind of cinematic scene that was a little bit different than all of the other ice and river and snow-related kind of shots in the rest of the film.

Loved the movie, VFX and SFX were great.

Absolutely loved the movie. But you think it could’ve been researched some better. There are no wild pigs or pheasants in Alaska.

Other than that, by far one of the best movies ever made!!!

Loved the dog, loved the man. Chanced upon this article while searching for locations of the shoot of the final cabin scene :))

So much work done to make the movie fun exciting and almost real, but why ignore the fact that it does not get dark in the summer and there are no fireflies, pheasants or wild pigs in the klondike? Was this just for some inside humor?