The book goes deep on Ub’s animation and photographic effects contributions.

It’s hard to list all the many accomplishments of Ub Iwerks. He was an animator (responsible for designing Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and Mickey Mouse), a major contributor to the field of photographic special effects (working or improving upon multi-plane cameras, optical printers, travelling matte photography) and an accomplished special effects, camera and projector technician, helping to deliver major theme park attractions still in operation around the world today.

Among other accomplishments, Ub won two Academy Awards (relating to color traveling matte composite cinematography and designing an improved optical printer for special effects and matte shots – the feature image above shows Ub inspecting the special prism inside his new camera used in the sodium traveling matte process). He was also nominated for a Special Visual Effects Oscar for The Birds, and was anointed a Disney Legend.

Now, Ub’s son Don Iwerks – himself a Disney Legend – has written a book about his father called ‘Walt Disney’s Ultimate Inventor: The Genius of Ub Iwerks.’ Don spent several years working alongside Ub, as well as making many of his own technical contributions to filmmaking and special venue attractions.

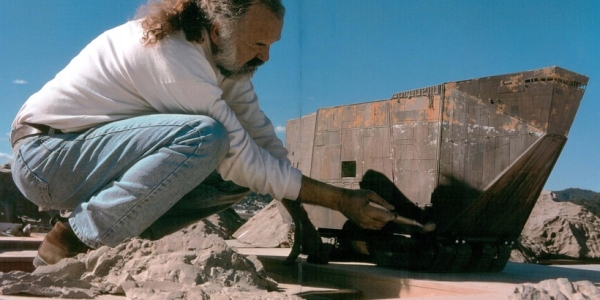

I’ve had a chance to read Don’s book, and it’s fascinating. Not only that, the book is full of behind the scenes imagery featuring Ub’s, and Don’s, work in many areas. When you flick through the pages, you can’t not think about the innovation and ingenuity at play for so many years. And of course all this is prior to the advent of digital photography and computer generated imagery.

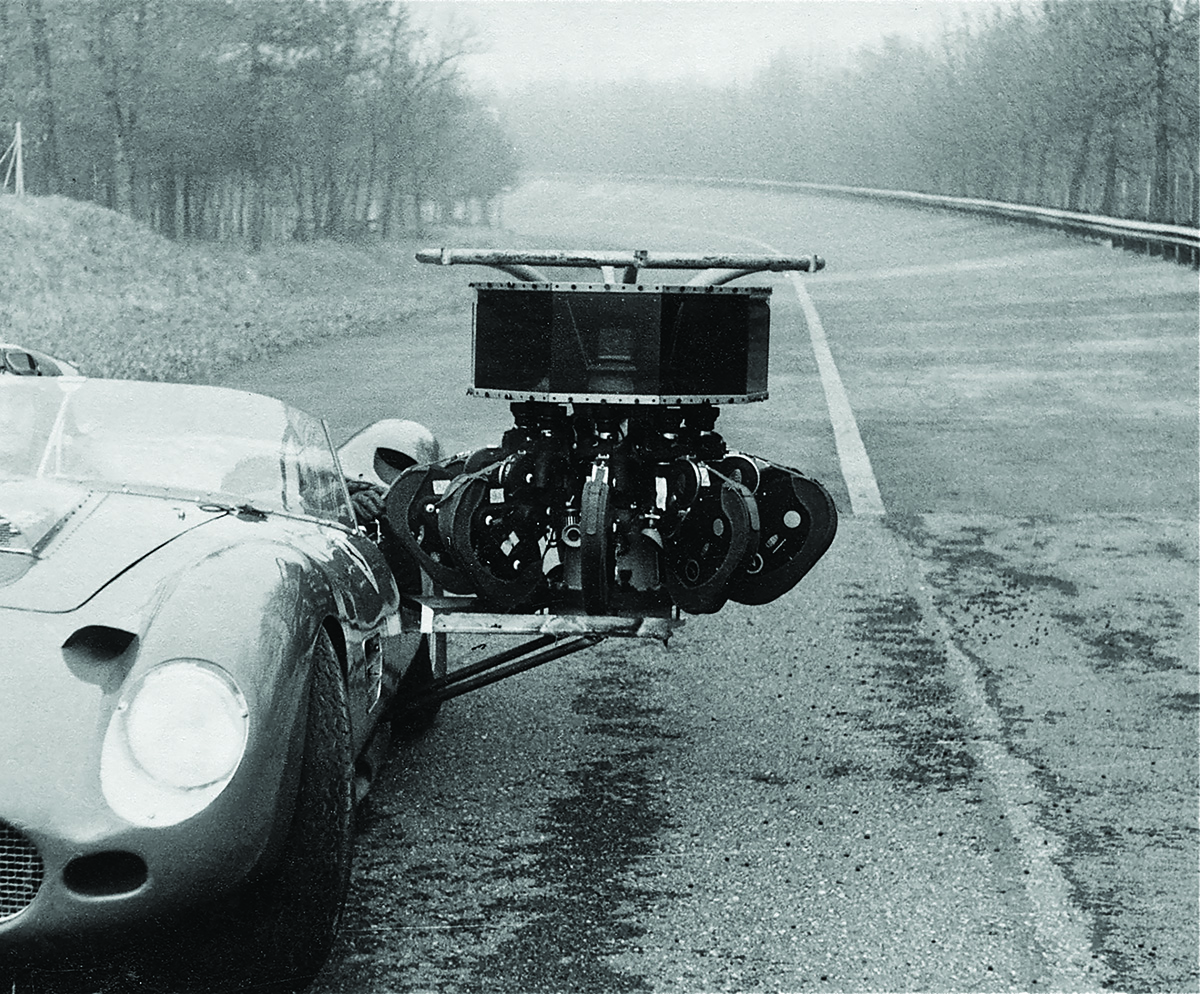

One section of the book struck me as particularly interesting: the development of a 360 degree camera system that could photograph – and later project – film in an immersive circular environment.

Today that of course is not something considered very difficult in terms of multi-camera arrays and also multiple projectors, but back then it was something that had to be engineered – using film cameras – in a way that allowed for the cameras to be loaded, synchronized and moved around.

When Ub did help develop such a camera system called the Circarama, at the request of Walt Disney, the resulting films were a big success. But one thing had been nagging Ub – since the eleven 16mm cameras had to be mounted in a particular way to fit their lenses, they actually ‘missed’ a section of the 360 degree scene. This produced a void area, and during projection the void was handled by vertical screen dividers. Ub wanted to no longer have that void.

I asked Don Iwerks, who ended up helping Ub on the Circarama camera and ultimately on the later configuration that would get rid of the void area, about that time in the mid-1950s.

Don Iwerks: I was what we called a camera mechanic or camera technician to go out on location on that very first shoot with the original Circarama. ‘Tour of the West’ was the name of the film and that’s the one that we allude to in the book. Walt mentioned to my dad, ‘You know, if we could develop a 360 degree system, we could perhaps find a sponsor and have an attraction at Disneyland.’

Well, it all happened. We built the system using Kodak Cine Special cameras. The thought at the time was we should shoot in 16 millimeter because, with that system, if there’s a camera jam and one camera jams, you lose them all. And there were 11 cameras in there, so you would have lost 10 other cameras that had been shooting just fine. But it isn’t a scene with one missing.

At any rate, we developed ways to ensure that if there was a failure, we would know it immediately and we could shut the camera down and fix the problem and get a re-shoot. But we really didn’t have much of a problem with that. It tended to work just fine. It seemed like after every shoot we would bring the camera back and would want to make some improvements on it.

We went through that first show and it was a very popular at Disneyland. That led to the next project, which was the U.S. pavilion at the Brussels World Fair in 1958. The Department of Commerce came to the studio and asked if it were possible for them to make a film about the entire United States. They thought that was a great way to show the country and it would be a wonderful exhibit for them.

Walt agreed. With some number of other upgrades, we shot that first show for the Brussels World Fair with our original camera, the 11 camera array in 16 millimeter. When that was done, other people of course saw it. The Fiat people from Italy saw it and they wanted to do a film about Italy. There was a centennial celebration coming up in 1961. And so Walt agreed to it.

The business that we describe in the book about void areas – areas not being photographed between the cameras – was something that was really bothering my dad, always did. So he figured, ‘Well, here we’ve got a brand new project that could pay for a way to solve the problem.’

He was the one that solved it. One morning he walked into my office and he said, ‘You know, there’s probably once in a lifetime that there’s one and only one perfect solution to a problem.’ He said, ‘Give me a pad of paper, I want to draw something for you.’ So he sketched out his concept of locating the cameras vertically and shooting upward into mirrors that were placed at a 45 degree angle. That distance from the intersection of the mirror to the lens was the same as the distance from that same point to the center of the system. So, it was just as if, by reflection, it was just as if all of the lenses were right in the center.

We got the okay to build that camera. I went on that shoot to Italy, initially to train the Italian technicians and the camera people. But after being there for a couple of weeks, the producer of the film decided he wanted me to stay there. He said, ‘We’ve already paid for your way over and back. I’d just like that insurance that your hereif we have any problems.’

So I stayed with them for three months while we traveled all over Italy, and down into North Africa and all the way down to Zambia to the Kariba dam which the Fiat engineering group were involved in building. We flew the camera in an aircraft and we flew it on boats and cars and so forth. For me with a wonderful time. I’ve had so many wonderful times at Disney and the 360 degree projects were just one of them.

‘Walt Disney’s Ultimate Inventor: The Genius of Ub Iwerks’ is full of so many other stories of innovation just like the Circarama one. I’d definitely recommend it for special effects aficionados. You can find the book at Amazon.

Wow what a find.Thanks for posting this gem