Inside the old-school modeling process with Pixar’s Bill Reeves.

These days if you want to model a CG character, there’s a myriad packages you can jump into – Maya, Max, ZBrush, Mudbox, Modo, etc – to get started.

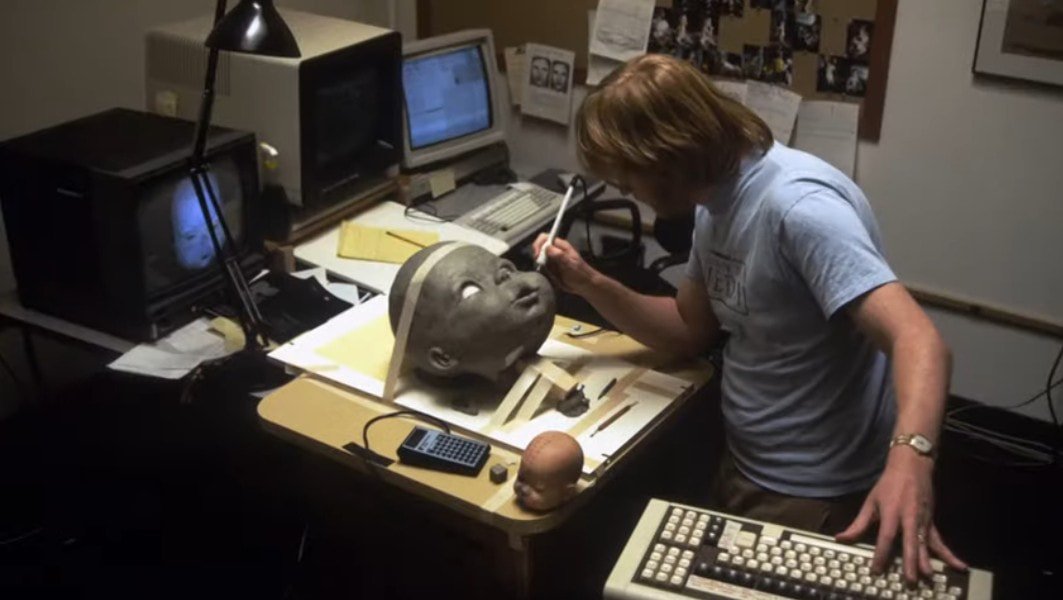

But back when Pixar was making Toy Story, which was released in 1995, the process was a little more arcane. A common methodology for digitizing a model at the time was to actually make a clay sculpt, mark it up with grid lines, then use a pen-like input device to make individual vertices on the sculpt, and transfer those points to a CG version.

That painstaking process was how characters such as Woody and Buzz Lightyear began their lives, and it’s something I asked Pixar’s Bill Reeves, now global technology supervisor at the studio, and an employee there since 1986, about at this year’s VIEW Conference in Turin.

b&a: Obviously these days modeling CG characters is a well defined process commonly done directly in say Maya. But back then it was a very different process. What was involved for Toy Story?

Bill Reeves: Well, at the time we were using Power Animator, it was one of the pre-cursors to Maya, but it didn’t have really great sculpting mechanisms. I think it was all NURBs curves, if I remember correctly.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]If you had to go to the bathroom you just had to hold onto it because you might forget where you were.[/perfectpullquote]

And those were nice and smooth and you can generate really pretty looking cars and stuff like that from them, but they weren’t really good for facial geometry or arbitrary kind of character geometry. This was before sub-division surfaces really took off. Subdivs is what most people use these days.

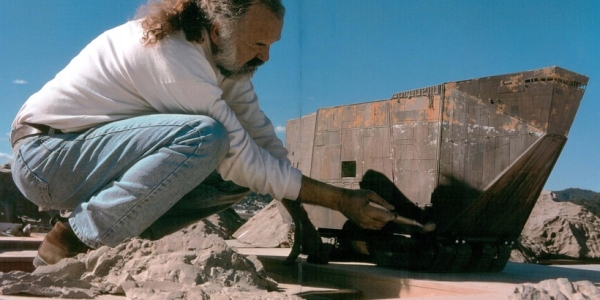

So, since the raw sculpting mechanisms in the software weren’t great, we did a lot sculptures using clay or clay-like materials. We were lucky enough to find a couple of artists who were really good at sculpting and taking the 2D artwork that would come out of the production designer and the art department and try to form it in 3D.

This was really good for the director and everybody involved, as well, because then they could see the shape of the character in three dimensions, walk around it, put light on it and see how it reacts to things. And we still do sculptures today. We don’t do it for every character, but it’s still a really good way to deal with the three-dimensional nature of these things.

b&a: Back on Toy Story, how did it work once a sculpt had been done?

Bill Reeves: What we would do was digitize these sculptures and we had this old piece of equipment. I guess we got it sometime in the 80s, it was a Polhemus digitizer. It was like a wand you could hold in space and the tip of the wand was where you would sample a point. And so you would take your sculpt and mark it up with grid lines and then go one by one and digitize all those points.

You would digitize the points in order and it would give you this big cloud of points. Then you could turn those into polygons, and then you could turn those polygons into NURBs, and then into the final shape.

It was pretty laborious. It’s like the guys in Star Wars who were doing stop motion – you couldn’t take a break. If you had to go to the bathroom you just had to hold onto it because you might forget where you were. It was better if you could just power through the left side of the face, or all the hand, and then stop. It was kind of funny in that way.

Also, marking those gridlines, you’d have to learn what worked best with your skinning technology. Then once you had the skin – the NURBs surface – you then had to work out what worked best with the animation system you had behind it to make it move. And there was a learning curve there. So, we did some bad ones and we did some good ones, eventually.

b&a: Did scale of those sculpts matter? Did you work out early on that the maquettes or sculpts needed to be a certain size to help with the digital scriber?

Bill Reeves: Woody would have been an 18 inch tall sculpt. It mattered how big it was because the precision of the digitizing system was only so good. And so you didn’t want something that was two feet fall because then you’d lose precision there. Or if it was two inches tall, you couldn’t get in there to digitize stuff. So about a 15 to 20 inch scale head was about right. We did bodies, too. I think the green army man was a sculpt and we had his whole body, but it was maybe two feet long and we would lay it on top of the digitizing table flat down rather than standing up.

b&a: What was the translation tool between those points and an actual CG model?

Bill Reeves: It went into our animation tool called Marionette. We actually had the Marionette pieces of the animation system before we brought Power Animator into the studio. We actually used the digitizing process and the animation system on Tin Toy, one of our short films. So, this process really dates back into the shorts.

Essentially there was a tool that allowed you to wire the models up after digitizing and figure out the meshing topology. And then there was another tool – just because it seemed easier to build a second tool – which was the animation system, which was based on muscles for the face, and pushers and pullers to push the points around, and that’s how we animated them.

b&a: Just with Tin Toy, which came out in 1988, I think you were modeling the baby in that short with this process. What do you remember was particularly challenging about that?

Bill Reeves: That was our first real attempt at a human. This was, as I said, before we had Power Animator and the NURBs process. I had been searching for a way of doing a surface representation for the geometry. I could digitize the points. That was fine. I knew how to do that and that was all good. But how do you skin it? What technology do you use for skinning? So I was searching for an answer to that and I found a bunch of papers, although I didn’t find the sub-division surface one along the way, which I wish I had because I might’ve been able to use it. You know, that baby was the ugliest thing you’ve ever seen for the longest time. And the end result is not something I’m really pleased with, to be honest.

b&a: But it ultimately has a presence in the film, doesn’t it? A menacing presence.

Bill Reeves: Oh yeah. And that was the first facial stuff we did as well. It was enough to tell that story and to win an Academy Award. So there you go.

b&a: With the digital scribing method, this is something you were using in the 80s and 90s, and other VFX studios and animation studios were doing it too, but do you remember when you stopped using the process?

Bill Reeves: Some of the characters from Toy Story 2 were digitized and Geri’s Game, as well. What happened was, on A Bug’s Life, the first character where we didn’t do it was for Hopper. We had this great guy, his name was Damir Frkovic, and he was a master sculptor. He could just use that software. We used him on Toy Story for a ton of props and set pieces. He was just fast, quick and efficient. And he got the idea of building just simple geometry, not overly complex, to fit within the box kind of idea. He was really good at that. We gave him the chance to model Hopper and he nailed it pretty well. I think Flik was a digitized sculpt, but Hopper wasn’t.

Then eventually 3D scanners and Lidar scanners came along, and we were able to use that process on a few films as well. So we transitioned over to these cyber-scans, but eventually that became too much data. I mean, they just generate so much data that you’re back to the skinning problem again. Which data do you use? We didn’t want to use all that geometry, all those points. We wanted something simpler that was efficient and fast in terms of what would be on the animator’s desk. So we needed low point counts, essentially.

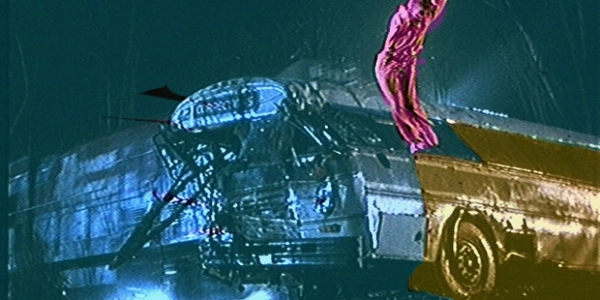

That’s when we transitioned. It was also when the Maya tools got really good and then people coming out of school were trained in doing characters using Maya and doing it by hand, straight into the machine. For Cars and the Cars films, we still did sculpts. A lot of the early CAD tools were obviously for the auto industry, so it was natural to do sculpts that way.