The film’s director and key ILM crew share their stories on ‘The Mask’s’ 25th anniversary.

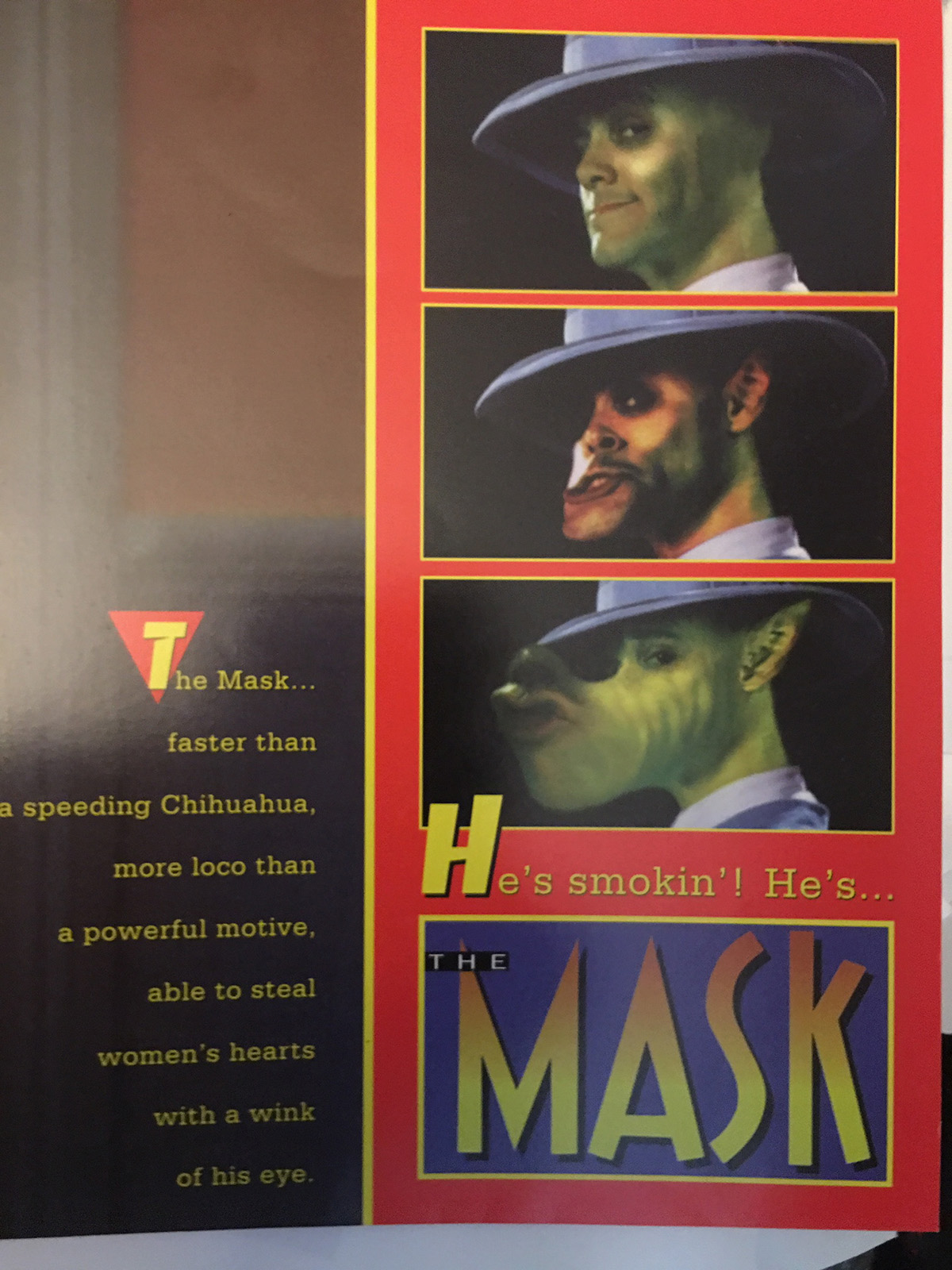

Twenty-five years ago, a relatively small film with ambitious visual effects was released that managed to make a splash with audiences. The film was The Mask, directed by Chuck Russell and starring Jim Carrey, who transformed into a crazy super-human any time he wore a mysterious mask.

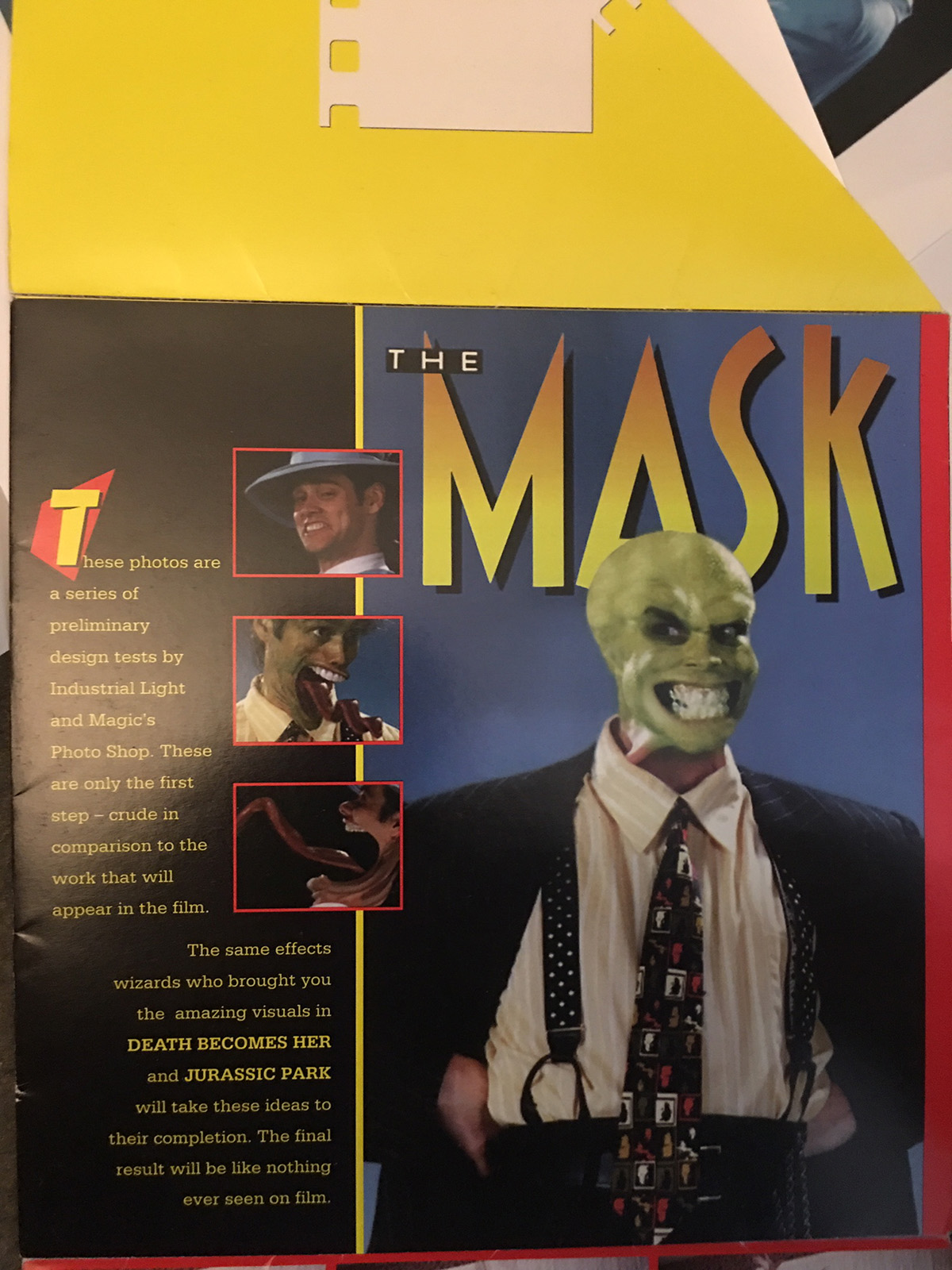

Those transformations would be largely handled by ILM, which had not that long earlier delivered the groundbreaking CG dinosaurs of Jurassic Park. For The Mask, the VFX studio had to now adapt their new (and growing) expertise in digital visual effects to more comedic-driven shots.

To celebrate the quarter-century anniversary of the film, befores & afters asked director Russell and several key members of ILM’s team to re-visit one particular sequence in which Carrey’s character first encounters the singing Tina Carlyle (Cameron Diaz) at the Coco Bongo nightclub, and descends into some outlandish mask-driven metamorphisms.

Imagining the nightclub scene

Chuck Russell (director): What was a very strong influence on my childhood was re-runs of Tex Avery. And that scene in nightclub, it really all came down to the ‘Red Hot Riding Hood’ Tex Avery piece. I thought, if there was a magical catalyst that made your craziest emotions realized, and then you got your first look at Tina singing in that nightclub, then this is what might happen. And Jim was capable of doing that almost even without CGI.

Benton Jew (art director, ILM): It was an homage to the old Looney Tunes, but done realistically. At the time, people were just learning about what could be done with CG. Off the success of The Abyss, and Terminator 2, it seemed like the possibilities were endless. We were getting all kinds of bids for films like ‘Plastic Man’ and other stretch-y-transform-y projects. The Mask was the first one to stick. It gave ILM a chance to stretch the boundaries even further.

Scott Squires (visual effects supervisor, ILM): All of us loved the Tex Avery style and just the irrelevance, just the whole approach to that. Certain things work well in cartoons but then when you say them portrayed as live action, you get kind of this not fish nor fowl type of thing. So we paid attention to that while we worked on the project just to make sure it was where it needed to be for the film itself.

Still at the dawn of CGI

Chuck Russell: We didn’t, or I, anyway, didn’t know exactly for sure if it was possible, but I thought CGI might be ready, and it was a perfect marriage for me with Steve Williams and the ILM crew.

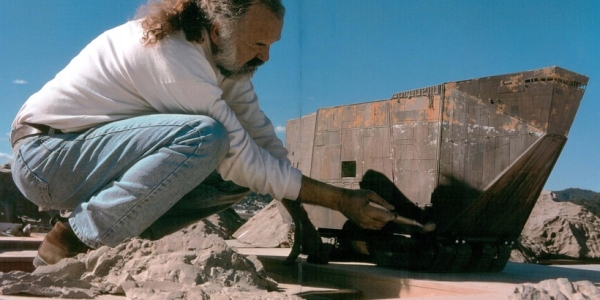

Steve ‘Spaz’ Williams (animation supervisor, ILM): In Jurassic Park, we were building dinosaurs, and they were the CGI creations. That had its own challenges, but in the case of The Mask we were literally doing an effects movie where every shot had a different type of problem AND we were doing it all digitally. And then the difference was, the effects weren’t supposed to wow you. They were supposed to make you laugh.

Scott Squires: It was not that long after Jurassic Park, so we had to deal with all the somewhat primitive tools at that time in terms of animation, in terms of texture manipulation. Some of the difficult tasks were him pulling off the mask, getting that stretching effect, and even the spinning effect, trying to do the motion blur and make that look interesting. And then being able to expand and contract the 3D volumes, like when he hits himself, and deform them, and going back. And then we also intermixed with 2D graphics and other things compositing, like when he’s swallowing the dynamite and so forth, his stomach expands.

Cartoony…but real

Chuck Russell: We did a number of concepts specifically for that scene, and actually that scene represented some of the most extreme concepts we did; the jaw-drop and the tongue roll-out, with the eye-balls popping out, and the other extreme concept was the eye-ball skull thing at the beginning of the Cuban Pete number.

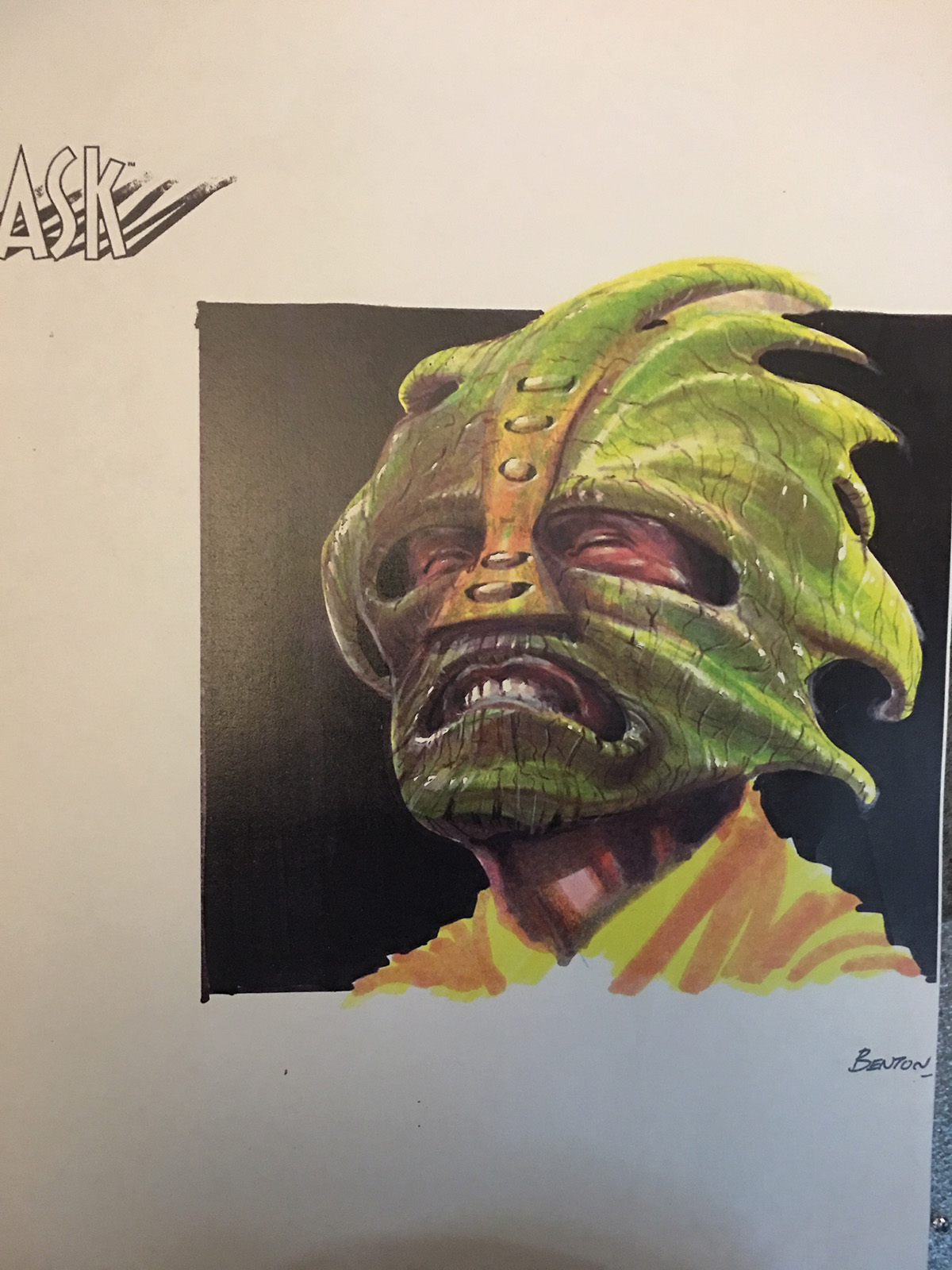

Benton Jew: The tongue roll shot was a lot of trial and error. At first, I did a lot of marker sketches and some Photoshop renderings after Jim Carrey did a little photo session with us. Later, after stuff was shot, we would look at dailies to see what worked and do more renderings as needed to see where we were.

Steve ‘Spaz’ Williams: I remember doing an interview saying there was really a fine line between it being hilarious and it being grotesque because adding specular highlight and proper drop-off and shadow and stuff does add a different element. It actually kind of takes the edge off the comedy a little. Especially, for example, the wolf head. I remember discussing it with Chuck – I won’t say arguing – but discussing with Chuck and saying I didn’t think we should do it so three-quarter. We should do it more orthogonal or flat like a Tex Avery. A lot of those guys were very good at drawing profile, like Chuck Jones and Tex Avery. They didn’t really get into this three-quarter shot stuff.

Benton Jew: There was a subtle balance between how cartoon-y and how realistic we wanted it to be. We wanted realism, but we also wanted to pay homage to the great animation masters like Tex Avery and Chuck Jones. You don’t want it to be flat and too simple like a toy balloon, but you don’t want it to be so realistic and organic that it looks like a horror movie.

If you’ve ever seen the photo-realistic interpretations of Beavis and Butthead, Popeye, or the Simpsons, they can be downright horrific – beautiful in their own right, but not what we were going for. I think we struck a pretty good balance. Sure we could have gone more over-the-top on some things, but that would’ve been gilding the lily.

Shooting the scene

Scott Squires: It was amazing to have Jim Carrey in that great Cannom Creations make-up, and then be able to transform him into the different characters. Jim spent like three hours in the morning getting into his make-up, and then would come in singing show tunes on the set. It was great. We also did a lot of night shooting – one night he had the make-up people do the entire crew with the little ring around your eye, like the dog on The Little Rascals.

Chuck Russell: Jim Carrey is a brilliant physical comedian so once I talked him through, ‘Okay, you’re gonna whistle, but your snout is extended out to here,’ it ended up being a perfect marriage of his being able to imagine it and physicalizing it and our visual effects team enhancing his performance, rather than replacing it. I didn’t want Jim completely replaced – obviously his head was in those shots – but it was always Jim’s performance.

Scott Squires: For the shots at the table, on set we’d be discussing, ‘Okay, well, should he do this first, or should he react to that? And how is that timing? What’s the placement of his hands?’ And of course you’re counting on Jim to follow through and hit in the right spots and do different things as well. I think we had some clips or something – Tex Avery maybe – but it’s not like we had the full video on our iPhones or anything, because obviously none of that existed. So it was just talking it over and trying to choose angles that would work. And John Leonetti was the DP on that, so he was great to work with as well.

We also were going to have quite a bit of interactive animation. So we had to think ahead and go, ‘Okay, his head’s going to expand for this,’ like when he does the whistle, he’s got to put his fingers out a certain length to compensate for that. And so that was one of the more challenging aspects, was just making sure the placement and timing was going to allow for the animation that we wanted at the end.

Making the shots

Scott Squires: Back at ILM, we’ve got Jim’s face, and then we start essentially morphing it. We’ve got a scan of his head, and we morph from that model to the other model. But it’s being essentially hand animated in that morphing process. Once he turns into that character, then we felt we could take it pretty far and actually push it as much as possible.

Chuck Russell: Some people just think you hire ILM and your movie just comes out. I worked very closely with those guys from the very beginning right through to the end. And then, I storyboarded this very carefully, so in a way, the editing was just tightening up the storyboards. This much new technology, there was very little that wasn’t planned carefully going in.

Steve ‘Spaz’ Williams: For the shots at the table, they’re all different models per different shot. The wolf head is completely different than the tongue shot. The audience might have thought, ‘Oh, it happens all in one shot,’ but they were cut-aways. It’s always a different model, a different set of data. We – me and [animation supervisor] Tom Bertino – would be showing Chuck all this stuff as it went along.

Chuck Russell: I work with visual effects artists like I work with my actors. I find out what the vocabulary is and I’m trying to get them to do their best and supporting them all the time. So I like to know my animators and I like to get involved and know which animator’s doing what. I’m around a bit like the evil art teacher looking over their shoulder as the process continues.

Steve ‘Spaz’ Williams: We were animating in Softimage. The wolf head was a very simple set of geometry that I built, whereas extracting the detail of Carrey’s face with the make-up on was very high in density in terms of data; it was a Cyberware scan from a bust. Somewhere in that transformation, I substituted out that data to the wolf head data which was low resolution b-spline patches at that time. Somewhere along that line we did a morph, not a real model interpolation. Of course the audience doesn’t see it. You’re dealing with green which is very forgiving and doesn’t have a lot of detail in it, and so there was a little bit of paint work to do that transformation.

Benton Jew: CG was a lot more limited in those days. We did the best we could with the tools we had. There was a lot of feeling out with what we could and could not do, and how far we could push it. I think it turned out great for the time, and I think it still holds up with most audiences today.

The impact of the film

Chuck Russell: It was a spectacular release. And the success was very humbling. At the time, New Line was a smaller company, and it was a very independent company, so it was a relatively small Indie film with a young group of filmmakers. Cameron Diaz had never acted before. Jim had just done Ace Ventura, but it wasn’t out yet. So our hearts were on our sleeves, but we were a happy, hardworking, crazy group of people. And that vibe I think shows in the film, that was so much fun.

Scott Squires: As we finished up the film, I had to go off the Slovakia for DragonHeart. So I didn’t see the film in the theatre with an audience until months later! And it had its run at that point, so there were like six people in the theatre. So unfortunately, I didn’t get the first-hand experience that I would have liked to.

Race to the VFX Oscar

Scott Squires: For the VFX bake-off, at that time, each film could go ahead and make their own short videos for Academy members, i.e., send it out to the Academy members so they could see before and after types of things. Then they stopped that process for a while and now it’s back so you can see it online. So, we had made the video that showed before and afters and it was really compelling. We submitted that to New Line to use. And then what they released was something totally different! Of course, they dropped all the more interesting effects work. And they put some odd music to it, and then they used like an old Western font for it – we were just amazed how truly terrible it was.

[The Mask (Scott Squires, Steve ‘Spaz’ Williams, Tom Bertino and Jon Farhat) ended up being nominated for the VFX Oscar along with True Lies and Forrest Gump (the eventual Academy Award winner].

Steve ‘Spaz’ Williams: I remember I brought my mom to the Oscars, and Letterman was hosting it. Of course everyone’s in black tuxedos. So, what did I wear? I wore a brown cord suit that I found at a second-hand clothing store. My mother was mortified, and I had a plastic lobster on my lapel.